Brian Rickard was aboard the FPB64 Sarah Sarah on her recent passage from New Zealand to Washington’s Puget Sound. Along the way Brian accumulated video so that we would have a chance to evaluate how Sarah Sarah did in various sea states. This was never intended for general public viewing, but the videos are so informative we thought you might like to share them. And if you are really into the yacht design and the real world of ocean crossing think of this as an early Holiday present.

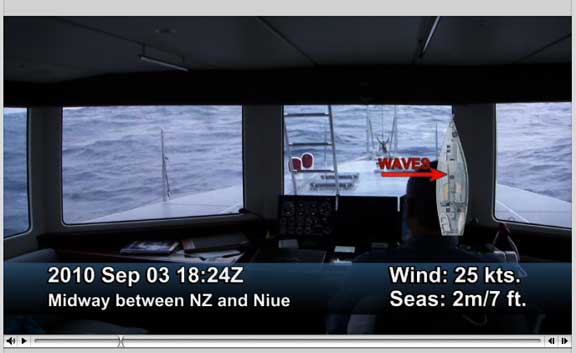

Each of the videos has a link in this blog, with our comments on what we are looking for and/or what the key points being shown are. A couple of general items to keep in mind. First, the camera always shrinks the waves. Unless there is a nearby frame of reference, the rule of thumb is to increase what the camera shows you by at least a third. Brian’s graphics on wind speed and wave size are for the average. Significant wave heights run a third to 50% larger. Wind gusts run about a third higher than the norm. Sarah Sarah averaged 9.33 knots between New Zealand and Niue, which applies to the first three video segments.

The Pacific Ocean is usually anything but, and while the dominant wind wave train is indicated the norm is to have swells from two other directions mixing it up with the wind waves.

In the first three segments, filmed between New Zealand and Niue, the NAIAD stabilizer settings were incorrectly programmed. This resulted in a much harsher ride than is normal. Careful observation will show you a significantly softer ride after Niue.

Finally, what we are showing you is the worst of what was filmed on the 6569 nautical mile trip back to the States. The majority of time conditions were much more benign.

So much for preliminaries. Lets get into the video. The first segment was filmed midway between New Zealand and Niue (a wonderful island). Seas are running two to occasionally three meters/seven to ten feet, and the dominant waves are on the beam. Click here to watch the first segment.

The next segment is filmed almost at the end of the first leg. The wind has switched to the southeast, has dropped a bit, and seas are smaller, now down to 1.6m/five feet, and just aft of the beam. There are a couple of instances where the boat heels about seven degrees and then comes right back. The speed of recovery is a little quick for optimum comfort. Once the NAIAD settings are adjusted the accelerations from the recovery of a wave-induced heel like this will be significantly reduced. Click here to watch the second segment.

So far what we have been watching is pretty tame, but it is about to get more interesting. Approaching Niue a counter current and secondary swell pattern started to stack up the wind waves. What you will see in this next segment are much steeper waves, probably eight second period, which is a harmonic of the FPB64s natural period, hence a worst case scenario. There are several interesting encounters, and then a slow motion replay of the “best”. Click here for this segment.

The next section takes place on the final leg, 700 miles north of Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands. Sarah Sarah averaged 9.85 knots for this leg, so she is running hard and straight into the seas. In this part of the (so called) Pacific you will always have one or two crossing swell systems mixing it up with the wind waves. Note the pitch accelerations and keep in mind that 9.85 knot average speed. There is one segment where the anchor tosses some water on deck. Although it looks impressive, the slow motion replay will show very little volume to this. You can also see how quickly the windows clear. Heading off 45 degrees, to a sailing angle, would significantly reduce motion, but it does add time (and weather risk), so the best policy is to get the passage over quickly, especially in a fall passage across the North Pacific. The link for this video is here.

From a design evaluation perspective it is the rough conditions which are important to us as designers. We assume the same is true if you are considering the purchase of a vessel for serious cruising. But after all the less than optimal sea states we have shown you Brian has included something more soothing with which to end this presentation. The final segment is here.

If you would like to watch the entire video without interruption click here.

March 14th, 2011 at 2:17 pm

Interesting. But I would have preferred to hear the ambient sound from within the boat, so as to get a more accurate impression of how it is to cross an ocean this way. Very rarely, as in never, is a film improved by having tacky elevator muzak plastered onto the sound track.

March 14th, 2011 at 10:51 pm

Music on video is a debatable subject in our office, Eva:

That said, we have not found a good method of recording ambient sound under way.

August 18th, 2011 at 6:27 pm

I am impressed as I have been for many years with all your designs. However this departure from all that ‘Pesky String” to the power boat fits well with our own thoughts. My wife and I have been in the Marine Industry for 35+ years. I was wondering where the curve becomes a realistic hull form. We were looking to build or buy a light displacement power cruiser easily pushed. We had 8 knots cruise and 10 knots capable and under 45 ft as a goal. We are not so much interested in ocean passages as efficient coastal and Carribean cruising. That could change…..anyway your thoughts would be very much apprecieated.

Will Heyer

mwheyer@gmail.com

August 18th, 2011 at 9:47 pm

Thanks for the kind words, Will:

The FPB concept scales, if that is what you are asking. However, we have no plans at present foro a smaller FPB.

August 20th, 2011 at 2:17 am

Steve,

if you say “scaling” – or downscaling in the case of Will – to which degree you think comfort and offshore capabilities really can be maintained in a 80% model (50ft)?

Kind regards

Hubert

September 4th, 2011 at 6:45 am

Hi Hubert:

The scaling and comfort issues are tricky. Cruising boats get heavier for their length as t hey get smaller. Natural pitch periods change, and of course mass. We’d have to study how to scale down carefully as a lot of this has to do with the desired range, mass, and resulting hull shape. At this point it is safe to assume it would be an exceptionally comfortable boat at sea compared to other cruisers. The % of comfort is harder to quantify.