Big news in the FPB world. FPB 97-1 is underway, and the folks at Circa are hard at work, getting ready for the day when they start to cut metal. On our end, we are ever so pleased to have released hull shape 975-80-C for building. The process that brings us to this point is long, painstaking, and involves a mix of scientific analysis and black art (also known as gut instinct born of experience). As we tend towards obsessive about such topics, perhaps a few comments might be in order.

To begin with, you cannot possibly design an appropriate hull shape without an accurate estimate of weight and center of gravity. Parts of this are easily calculated thanks to 3D modeling. The computer assesses surface area, and then multiplies this times a unit weight. As an example, we know quite precisely the area of twelve and eight mm hull plate, and head and hull liner panels as well as their construction weights. There will be some variables from detailed engineering, but these are allowed for via various safety factors. Other items like batteries, engines, deck winches, window glass, and even light fixtures find their way into the calculations.

Things get interesting when we start to play what-if games with the fuel and water. In terms of fore and aft trim and vertical center of gravity, how the tanks are laid out and used have a substantial impact on calculations.

Once we have displacement and center of gravity scenarios tied down, the finessing of hull shape can begin in earnest. Here it is a question of trade-off between:

- Steering control

- Propulsion efficiency

- Initial and ultimate stability.

- Skid factors

- Motion at anchor

- Cruising slowly

- Running at speed

- Hauling out

- Using tidal grids

- Running aground

It is a complex brew, to say the least.

You will note that nowhere in the preceding was the subject of interior mentioned. While interior is obviously an important topic, in a yacht that is meant to entice its owners to cross oceans, to meander about the world on its own bottom, the design equation has to emphasize sea keeping and safety first, to which the preceding list refers. Distortion of an optimum hull shape for the sake of accomodations is a topic banned in our presence.

There are several distinct design objectives that have to be fared into each other. One of these is steering control, which on the FPB means:

- Balanced ends of the topside areas above the canoe body

- Moderate beam-to-length ratio

- Hull shape that does not change significantly change its center of buoyancy with heel

- Large rudder authority

- A forefoot that does not lock in when surfing at speed

Get this right and you have a wide range of storm tactics at your disposal, the ability to average much higher boat speeds in all conditions, and a significantly more comfortable vessel.

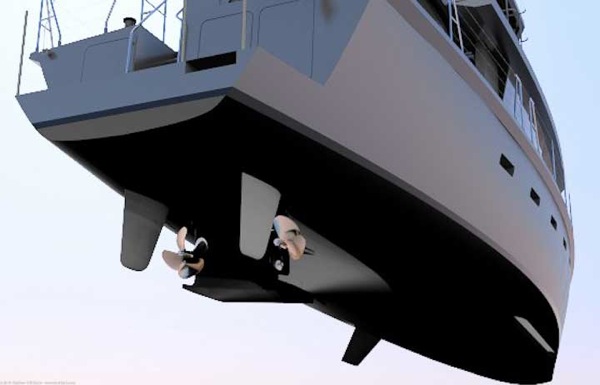

It doesn’t take a lot of staring at this hull shape to get your juices flowing. Can you imagine how cool this will feel, surfing down tradewind swells, watching the speed gauge climb from 11.7 knots to the high teens, while the autopilot barely blinks?

Next on the list is handling waves on the bow. Here we come across some potential compromises with steering control. The ideal wave penetrating hull shape is deep forward, narrow above the waterline forward, and narrow aft. If you start with a fat hull shape, you are forced into a deep forefoot to work with it. This leads to a locked-in bow heading down the waves, and that can turn into a broach and capsize situation. Not fun to contemplate, so the prudent tactic as the waves build is to slow down, which increases your exposure time, or turn around and head into the waves. Jogging uphill balances a reduction in broaching risk against being caught by an oncoming storm.

On the other hand, if you lengthen the waterline, reduce displacement, and then moderate the beam, you suddenly have a relatively shallow hull which is still knifelike forward, enough so it will slice comfortably through the waves, yet shallow enough to be easily steered.

That’s what you are seeing here.

In the context of heading uphill in moderate breezes, say up to 20 knots, this hull is so powerful, yet fine-ended, that it will barely feel the waves. As seas increase and perhaps steepen, one needs to make sure the increased longitudinal stability that comes with length does not force the bow through the larger waves. Put another way, it is desirable for the bow to lift to the seas before the waves begin sweeping continuously down the deck. Towards this end the FPB 97 has a touch more volume up high in her forward sections than is the case with her smaller siblings. Where this extra buoyancy would create pitching in the FPB 64, the 97 is large enough that the smaller waves will not feel this added volume in the upper reaches of the topsides.

As the wave travels down the hull it is going to apply a lifting force as it goes. If the stern is being buoyed by a wave, this generates a downward force on the bow. The narrower the stern sections, the less this will happen. At the same time, there needs to be sufficient lateral plane, in particular aft, to prevent the hull from squatting as it increases speed. The lateral plane also provides pitch dampening. But get too much and the motion becomes a high frequency mix of accelerations and decelerations, not a comfortable outcome. The FPB handles this with slight change in the aft lateral plane and volumetric distribution.

The last piece of this puzzle is stability. This is a function of displacement, vertical center of gravity, and waterplane inertia. We are concerned with this at rest, at speed in an upright attitude, and as the boat heels from wave impact. Initial stability is easy: add beam for more, subtract for less. But as you add beam, you quicken the roll period, and that is both uncomfortable and possibly dangerous. Beam also shallows up the hull, which tends to raise the VCG–a double whammy. We’ll discuss the stability characteristics in another post. For now, let us just say that we have an excellent stability curve both upright at anchor and underway, and positive stability through two and a half times the angle any conventional motor vessel can achieve.

We’ll have detailed posts on tankage and stability in the near future. There will be a full report on sea trials during the fourth quarter of 2014.

April 21st, 2012 at 8:03 am

You don’t show bow thrusters have they been eliminated form the 97’s? One would think the benefit of thrusters is greater with the longer hull? She has a striking shape but I still long for a 64. Will enjoy watching her construction and sea trials. Thanks.

April 22nd, 2012 at 1:02 pm

Thruster is still in the boat, although it will rarely be required. It just has not made it into the final hull shape yet.

April 23rd, 2012 at 7:00 pm

The second pic makes it look like a long, long bow. How far aft is the max beam, if that’s not an official secret?

April 23rd, 2012 at 8:06 pm

The position of the maximum sectional area is something we’d not lightly disclose. That said, it is not that far out of the norm, and there several other key factors with the curve ofo area, prismatic fore/aft, deadrise, rocker, and transom immersion, plus waterplane that play into the shape. A complex witches brew, not easily dealt with computationally, in spite of super sophisticated CFD codes, etc. But that is what makes designing this sort of project such a challenge, and appealing.

April 24th, 2012 at 12:11 pm

Okay, no problem. And the viewing angle on that pic might be exaggerating the effect. One other request though: on the FPB 115 page you have a composite of the three hulls together so we can see the scale. Is there any chance of adding the 97 and publishing that pic? Thanks!

April 30th, 2012 at 8:47 pm

When we get caught up, Martin, we’ll see what we can do.