Many years ago, while researching ultimate storm tactics for our book Surviving the Storm (free download here), it became clear to us that, whether it was Fastnet 79, Queen’s Birthday Storm, or the 1998 Sydney Hobart Race, heading into the waves is often the best tactic in severe weather.

Because our yachts surf downwind under control making quick passages, and since in all but one of the serious storms we have experienced our natural course was downwind, we’ve rarely had the chance to experiment with truly dangerous seas on the bow. And while this most recent experience is far from what we would call a survival storm, the unusual sea state did give us a chance to test several FPB specific steering and throttle techniques, along with gathering a couple of ideas for improving electronics and night lighting layout.

The notes which follow, although aimed specifically at the FPB fleet, may offer some ideas to others who find themselves in difficult seas…

Mariner’s lore contains stories of “rogue waves” appearing out of nowhere. This mischaracterizes these sea states. These are in fact statistically predictable, the result of wave trains intersecting with one another, currents, underwater features sometimes thousands of feet below the surface, or “dynamic fetch” (you can read much more on this topic in Surviving the Storm). If you spend enough time on the water you will eventually encounter them – hopefully seen at a distance from your precise location.

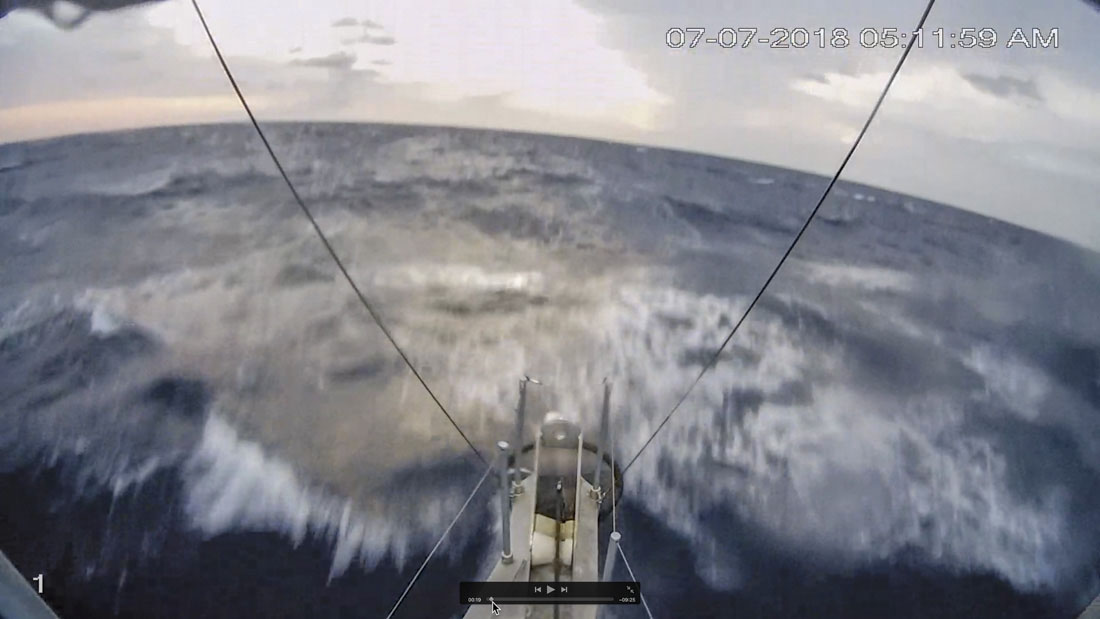

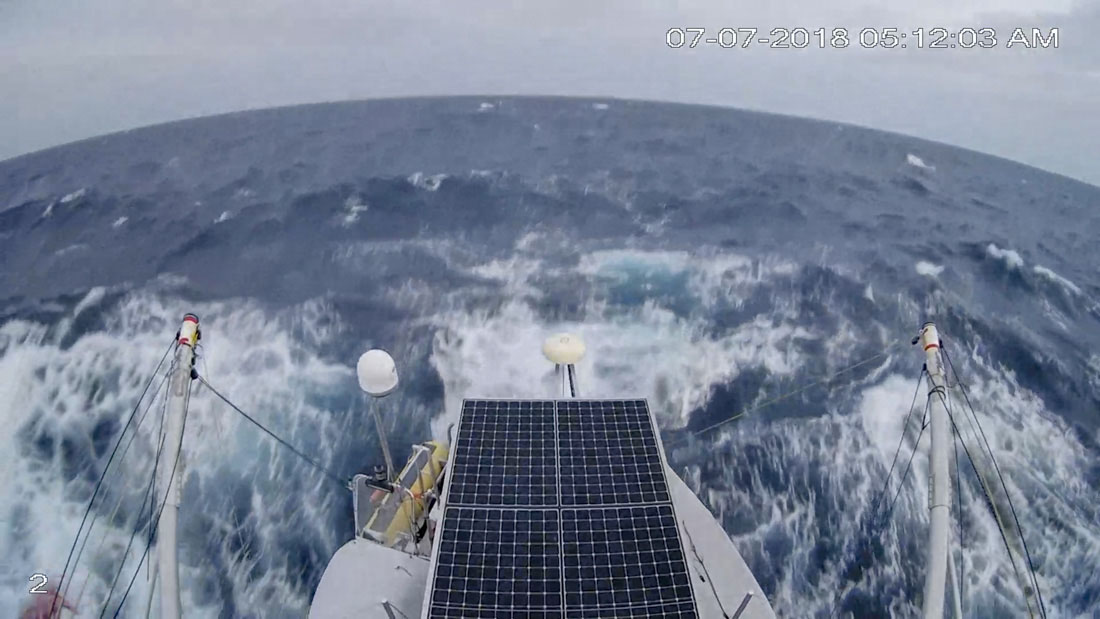

There are some remarkable photos in this post, the result of having recently installed a series of high-res video cameras and related recording gear. Without this we would never have been able to show you what the sea can be like, and why we feel strongly about certain design aspects of offshore voyaging. Keep in mind that these cameras all have very wide angle lenses (hence the curved horizons), which make the waves look significantly smaller and further away than they are in reality.

Cochise and her crew–the two of us and Corey McMahon–were enjoying a lovely 25-30 knot SW breeze, as we surfed downwind towards Maine from Beaufort, NC. We were headed outside Cape Cod, with a potential stop in Nantucket should our timing make this efficient. Not long after we departed the forecast indicated the chance of a moderate Nor’easter somewhere in the area of Nantucket. A day later two bands of intense squalls, with gusts to 40 knots, torrential rain and lightning announced the arrival of the new air mass. Of course this happened at night.

To us and to Cochise a 40 knot NE breeze, even if against the Gulf Stream, is no big deal. What made this situation different was the occasional head-on collision of SW swells and NE waves in just the right fashion to produce sets of three waves much larger and steeper than the norm. They were more vertical, and seemed to be moving more slowly than would normally be the case for waves of this size. As such, we think they gave us an indication of Cochise’s reaction to the cascading crests in an open ocean storm where the larger but more widely spaced waves have more fetch and time in which to develop.

The roughest part of this situation took place between 0300 and 0600.

This camera is 17’ above the waterline. The oncoming crest is steep, but not extreme from Cochise’s perspective. Looking at the photo, studying the angles, and knowing the lifeline stanchion top is 12 feet above the water we guesstimate the approaching crest is in the 20-foot range. What is more interesting is the next wave in this series which you can see forming up in the background. How the next encounter turns out is dependent on the reaction of the boat to the present wave as it travels down the hull. If this wave exerts too much force aft, driving our bow down, it will be difficult for Cochise to lift the bow in time for the next crest.

In a few seconds of waves, this event captures one of the reasons the FPB hulls look so different from other designs. It’s a more comfortable approach in more moderate conditions, and significantly improves heavy weather capabilities.

Above, the crest has traveled down the hull and is now just past the stern. The camera is set six feet above waterline, on the transom. The stern becomes more deeply immersed as the preceding crest passes by the hull. This has both rudders and props deeper in the wave making them significantly more efficient. The more beam aft, the more the bow will be depressed and stern lifted.

Comfort is very much a relative concept, and FPB 83 Wind Horse was a revelation to us in terms of comfort compared to sailing, to the point where we thought nothing of cruising direct from Hawaii to Ventura, California, 2000+ NM under the Pacific high and dead into the wind and prevailing seas. A NW crossing swell from the Gulf of Alaska created a chaotic sea state with wave peaks directly on the bow, yet we still averaged 11 knots for the passage as we marveled at how much more comfortable we were than would have been the case had we been aboard one of our sailboats.

There is a design tension between a hull configuration that is comfortable heading into the waves, one that surfs downwind under directional control, and that avoids “locking in” when charging down the wave face. In comfort and safety terms, downwind control is important in both heavy weather and normal downwind passages. If your hull does lock in and begin to “bow steer,” or the stern gets pushed around by the wave, the next step is a broach.

A few years with Wind Horse, and we had become used to this new level of comfort. When we drew the lines for the FPB 64 she was given a hull more adapted to making its way comfortably uphill, while retaining its ability to maintain steering control downwind.

We picked up valuable bench marks from the FPB 64, and when we started to noodle on the FPB 78 lines we thought we might improve the upwind comfort even more without undue negative impact on downwind steering.

Although the FPB Series look similar, each hull is its own unique blend of design elements. These vary with length of the hull and the wave size and period for which they are optimized.

The combination of canoe body shape, deck shear, mass, topside cross section, and anchor position of the FPB 78s is considerably different than the preceding FPBs. The finer ends, increased mass-to-waterline ratios, and higher shear were the subject of more than a thousand hours of drawing, testing, discussions, and over 500 hull variations drawn and tested. But even with all the design tools we have at hand these days, in the end how these elements are blended is very much a result of instinct, based on our own experience. We ended up with a more efficient hull shape at cruising speeds in the 9.5-10.25 knot range, but pay an increasing penalty above this speed compared to a hull which is more like the FPB 83 and FPB 97 – a cost all of the FPB 78 owners are happy to bear in exchange for the added comfort uphill and benefits when surfing in aggressive conditions (click here for video of Cochise surfing at 14-22 knots).

We are not trying to say that this is the only approach that makes sense. Other designers have different concepts based on the expectations of their clients and the trade-offs between sea-kindliness, the ability to deal with heavy weather, and maximized hull volume that works best at the dock. That the FPB 78 design approach works for us and the other owners is evidenced by the passages already made against the trades–witness Cochise’s 7000 NM Fiji-to-Panama voyage, and the more recent 4000 NM French Polynesia-to-Costa Rica trip of Iron Lady II.

Now a series of photos of the next crest, where it will become clear how the design trade-offs we have been discussing work in more extreme conditions.

How big is this wave? We are not sure, but we know for sure it is bigger than the preceding wave, so 20+ feet. Think about the wave as the fulcrum of a teeter-totter, with the fulcrum moving aft as the hull penetrates the crest. The relationship of the wave shape to the hull both below and above the waterline controls the outcome.

The three circles just forward of the bow are from spotlights mounted at the top of the mast, another six feet above the camera and about 23’ off the waterline. These spotlights normally hit the water about 80 feet in front of the bow.

There’s another aspect of the FPB 78 design that you can get a sense of in these next three photos. Notice the angle or shape of the spray pattern as the anchor, anchor platform, and wide rubbing strake come into contact with the wave. The relatively flat direction of the spray is indicative of the lift being produced by these surfaces. The substantial upward angle (when viewed from the side) of the forward portion of the hull creates an angle of attack with the wave rushing by that helps these surfaces generate lift.

There is now sufficient light for the cameras to record in color and they automatically shift modes.

The volume in the bow and stern above the waterline, together with the lift imparted by the forward horizontal elements, work together so the stern depresses enough to allow the forward buoyancy to lift the anchor platform over the crest.

Let’s switch to the camera looking aft mounted opposite the forward camera.

Here is the result on deck from this particular wave one second after the preceding photo.

And this is the big crest we just went through at the stern. Being significantly larger than the preceding crest the stern appears even more deeply immersed.

The bow is a touch lower heading into the next crest, the result of the previous crest lifting the stern a bit. Look at the time stamp on this and the preceding photo. Both are taken within the same second. Allowing for some wave and boat movement this gives us an idea of the distance between crests. Cochise is 86 feet nose to tail so the wave crests are probably no more than 100-120 feet apart. Like we said, very steep.

Although this looks like a snootful, in reality there is little water mass. With nothing to trap it the water clears in seconds.

Facing aft from the top of the anchor and steaming light mast will give you a sense of the wave shape. Cochise is pitched up as she lifts to the second crest in this series. Looking around gives a feel for what was going on most of the time; it’s not that bad. However, it’s these transitory events occurring every two to five minutes that are the bottom line. It would not be pleasant to get one of these wrong.

Three seconds later. This encounter’s wave crest and the preceding are clearly visible behind us.

Another important aspect of how your FPB or any other yacht is going to deal with head seas – normal or extreme – is the distribution of mass around the pitch centers of the vessel. These create what are called “polar moments” and are a geometric function of the distance of the mass from the point around which the hull is gyrating. This impacts both the pitch and roll period. Careful attention needs to be given to these weight centers during design and construction. How the payload is distributed will significantly impact motion as well. The right mix of polar moments is what allows a vertical center of gravity sufficiently low to enable capsize recovery, yet not result in a hull that has a jerky, uncomfortably “stiff” motion.

This fun began about 2300 the previous evening and by 0300 it was definitely getting interesting. Every few minutes we’d run into some of these gnarly sets. We began by hand steering using the Simrad AP 70 autopilot in follow-up mode. With a couple of hours of experimenting under our belts we found the following:

- Operating at the minimum RPM required to maintain steering control helped with comfort and in the steepest seas improved the entry angle to the oncoming crest.

- Engine speed varied in the worst of this from 950-1100 RPM, slowing to 600-750 for the really big crests.

- We experimented with several of our more aggressive work modes with Simrad doing all the steering. The combination of our “heavy running” mode and turning on the second hydraulic pump, as we do when docking, worked best.

- Note the twin pumps give us a rudder travel of 12.5 degrees per second. This very fast response coupled with our two large rudders made it possible for the Simrad AP70 to bring Cochise quickly back on heading, which in turn made it possible to run more slowly.

- Simrad doing the steering allowed us to concentrate on the waves and throttles. In a longer lived and more dangerous sea state this aspect would be critical.

- After 0800 with good visibility and less extreme occasional peaks we picked the speed RPM up to 1300-1450.

Our FPBs have a substantial amount of lighting power forward. While these lights are a great help when looking for ice or debris in the water and closing with the shore, their primary purpose has been to check sea state. Water tends to absorb light and to see effectively takes lots of illumination. With as much LED power as we have now–six very bright Rigid Industry spots and driving lights–we could see well enough forward to change engine power settings as needed with the different sea states in time to keep the boat comfortable. But for larger storms, with crossing wave trains we would like even more light. The idea of doubling what we have is now percolating.

The FPB 78s have emergency steering controls at both helms. Pushing a single button puts us in direct control of the backup hydraulic steering system. The autopilot and primary hydraulic system are disengaged. Our emergency JOG levers are located where useful on longer passages but otherwise out of the way. We are going to move both to where changeover is a few seconds faster.

We were never concerned with Cochise’s ability to deal with this situation structurally. The forward windows are specially laminated glass consisting of three glass and two plastic interlayers, 15mm/5/8″ thick. Side windows are double glass and two layers of plastic, 11mm/7/16″ thick. These laminate statistics have been tested hydraulically up to pressures comparable to what the Lloyd’s Special Service Craft rule requires in the topside slamming zone of the hull.

If anything had gone wrong with steering or the engine(s) lost power, and we were abeam of this series, well, that is why we have seat belts on all bunks and some seating positions. This is not the time you want to be wondering about preventative maintenance!

Our little experience here lasted less than 24 hours. It provided us with insight into tactics we might put to work in bigger blows lasting several days. It also showed us that we have the maneuverability to have a chance to deal with the crossing sea state that comes with a frontal passage and change in wind direction in more severe conditions.

How bad were these waves? In over 200,000 miles at sea we’ve only twice experienced anything similar. Once was running down the Irish Sea off the coast of Wales. It was during daylight, the bow dropped into a hole and a very substantial crest came rolling down the deck. With a harbor of refuge in our lee it took just that one sea to convince us to change direction and enjoy surfing to safety. The other was at night, between North Carolina and the Bahamas. We spent several hours in what must have been violently confused seas. We never saw them, but it is the only time motion has ever been severe enough for us to be totally airborne.

Corey McMahon, who has circumnavigated, crossed the Indian Ocean twice (once west to east with daily 60-knot blows), and numerous other trans-ocean passages has never seen anything similar. Corey likened this to a 100-mile long entrance pass or channel with standing waves. He echoed our own feeling that as long as everything worked we were fine. “I would not have wanted to be sideways. Yet I was comfortable enough to sleep on the Matrix deck couch,” he told us afterwards. Corey went on to say that “The station wagon effect in that breeze was impressive,” referring to the deposit of salt on the aft solar panels from spume. Corey reckons we were seeing a steady 40 knots at times.

The handling characteristics of each FPB are unique. Pete Rossin relates what they found in somewhat extreme conditions in the “Furious Fifties” with FPB 64-3 Iron Lady.

“We had a similar experience off the Banks Peninsula in NZ in 2012 during our circumnavigation on our FPB 64. No idea what the waves were but an un-forecast storm generated monster square waves right on our nose. We were later told in Akaroa that there was substantial damage shoreside and that they get one of these un-forecast monsters every few years.

As usual, it peaked at 2 AM and the winds were over 50 knots with 60 knot gusts. The whole event lasted about 8 hours and by dawn, it was over. There was so much spume and spray that the visibility was nil so I have no idea what the waves were, but we were literally being thrown out of the water off the tops. Our strategy was to pull back on the throttles and bear off about 20 degrees to lengthen the period between waves and soften the impacts. There was green water on the foredeck and lots of commotion but that was primarily from the anchor flukes busting into the oncoming waves. We never felt in jeopardy but, as you point out, the seatbelts were a must and we would not have wanted to be broadside in these conditions.I do not remember fuel/water payload but we had just left Queen Charlotte Sound at the top of the South Island bound for Stewart at the bottom and then it was on to the Fiords and up the west coast with no safe harbor, and then around Sand Spit and back down Cook Straight to Queen Charlotte again, so I am quite sure we would have been close to full fuel. Water load would have been modest to keep the gross down as that is the way we ran the boat.”

With a much longer waterline relative to wave period, the 110′ FPB 97 requires more throttle attention and steering in tightly spaced seas. Click here for a post and video showing a bit of this.

We want to emphasize that we do not recommend taking your FPB or any other yacht purposely into what could be harm’s way. On occasion, when the opportunity presents itself, we will do so, in order to learn. But we have a better chance than most of knowing where the limits lie, where curiosity turns into something potentially threatening, and when a situation could turn deadly. That said we do strongly recommend that you practice your seamanship techniques in conditions that are less than benign. Work your way up the ladder of wave and wind gnarliness. If there is a headland, with a steeper than normal sea state, use that to practice steering, pilot settings, and throttles.

Aside from preparation, crew skill, and luck, the best guarantee of success is patience, picking the right weather, and using boat speed to avoid bad weather in the first place.

A word about seaworthiness, what we have been discussing and vessel loading, particularly for FPB crews. The FPBs have massive tankage between fuel and water, and you can easily overload the boat with too much liquid. Those huge water tanks are intended to replace the weight of fuel as it is burned. We do not recommend full fuel and water – ever. Excess mass slows you down, more deeply immerses the hull, and makes it more difficult for the bow to lift to oncoming waves. Cochise was carrying 4000 gallons of her 7000 gallon total liquid capacity on this passage. We would not have wanted more.

We invite your comments, questions, and to share your own experiences, good and bad…

August 17th, 2018 at 12:56 pm

My vote for understatement of the decade: “But we have a better chance than most of knowing where the limits lie,”

Great post and pictures. Thanks for taking the time to write such a detailed description.

August 22nd, 2018 at 6:42 pm

Very well written. Most of you know it is difficult to nearly impossible to take a 2D photograph that depicts storm waves in their true fury, much less with a wide angle lens used here. There is no question in my mind if you put yourself in a position to encounter seas like these an FPB is the way to go, even more so than much larger mega-yachts that are designed for a different purpose. The safety key here is accurate weather forecasting and following the ‘rules’. Leave for a long passage during the ‘right’ time of year and an event like this is extremely rare. In our personal travels including a high latitude circumnavigation we had real weather, and nothing even close to this, only twice and we put ourselves in that situation voluntarily. We considered ourselves chicken of the sea. One pet peeve we wrote about often was a schedule was the most dangerous thing on a boat. A stretched long weekend knowing it should be cut a day short because of coming weather and so on.

We’ll get off the soapbox with words from a former powerboat circumnavigator: “Anyone who has seen big seas, doesn’t wish for big seas”.