We get a lot of questions about range, fuel burn, boat speed, and how this works out in the real world. Whether you have an FPB or a trawler, the same basic issues apply. In this blog we are going to review the factors which impact the fuel equation and then compare data for several different types of vessels. The photo above and below of the FPB 83 Wind Horse, were taken in Gibraltar, a favorite (low cost) fuel stop.

We get a lot of questions about range, fuel burn, boat speed, and how this works out in the real world. Whether you have an FPB or a trawler, the same basic issues apply. In this blog we are going to review the factors which impact the fuel equation and then compare data for several different types of vessels. The photo above and below of the FPB 83 Wind Horse, were taken in Gibraltar, a favorite (low cost) fuel stop.  Range is a complex subject. Not only does it affect where you can go and how fast you get there, but it also impacts options for refueling. The more range you have, the more choices on price and quality that are open. If you can barely make it across the ocean, say to the Marquesas Islands from Mexico or the Galapagos, then you are going to pay 50/75% more for your fuel than will be the case 1000 miles further along in Tahiti. Having smooth water performance numbers is just the first step. Real world range has to allow for a variety of factors including:

Range is a complex subject. Not only does it affect where you can go and how fast you get there, but it also impacts options for refueling. The more range you have, the more choices on price and quality that are open. If you can barely make it across the ocean, say to the Marquesas Islands from Mexico or the Galapagos, then you are going to pay 50/75% more for your fuel than will be the case 1000 miles further along in Tahiti. Having smooth water performance numbers is just the first step. Real world range has to allow for a variety of factors including:

- Consumption for propulsion.

- Power (electric and hydraulic) generation.

- Heat (either electric or diesel boiler).

- Rough water drag.

- Stabilizer (active or fish type) induced drag.

- Windage.

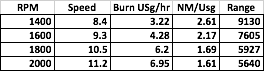

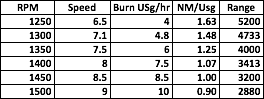

Heating, air conditioning, and other electric consumers will eat into range under way. If you are genset dependent, and run the generator 24 hours a day on passage, then anywhere from 12 to 30 gallons /45 to 113 liters a day is going to be used. Rough seas and windage can easily decrease mileage by 15% to 50%. And then there is the question of fuel capacity. It is often the case that usable capacity is overstated. If you are looking at long passages confirming how much fuel you can actually load into the tanks is prudent. There is also the concern about what is sitting in the bottom of the tank(s). If you haven’t cleaned the sumps in a while, it is best to leave the bottom of the fuel tank out of range calculations. Speed and range is directly related. Well designed trawlers can run efficiently at speed length ratios up to about 1.05 or 8.0 knots on a 58 foot (18m) waterline. The drag curve after this climbs so steeply that going faster just throws away fuel (The FPB 64 can run at SLRs of 1.2/1.25 (9.8/10 knots) efficiently because of the hull shape). Why go faster? Because speed and safety are directly related. The faster you go the less weather issues there are, and the more tactical options you have if you end up dealing with less than pleasant conditions. Now some numbers. Along with our data on the FPB 83 Wind Horse and the first three FPB 64s, there is lots of info on fuel burn on the web for trawler yachts, some of which we have included here for reference. Lets start with Wind Horse.  This data is for full load. Over many thousands of miles, with full fuel tanks at the start refilling at the end, we have run at 11 knots for between 6.7 and 7.3 gallons per hour. Adverse sea states cost us on average about 15%. If the breeze is behind us, that helps by five to 15%. We do not need to run a generator at sea, but the electrical loads supplied by DC alternators, still take power from the engines, and therefore burn fuel (but less than a genset running 24 hours a day). Now the FPB 64 with its extension, this data based on recent sea trials.

This data is for full load. Over many thousands of miles, with full fuel tanks at the start refilling at the end, we have run at 11 knots for between 6.7 and 7.3 gallons per hour. Adverse sea states cost us on average about 15%. If the breeze is behind us, that helps by five to 15%. We do not need to run a generator at sea, but the electrical loads supplied by DC alternators, still take power from the engines, and therefore burn fuel (but less than a genset running 24 hours a day). Now the FPB 64 with its extension, this data based on recent sea trials.  Note that this data is for a lightly loaded configuration without auxiliary loads. It is comparable to the data which follows. In digging up fuel burn data on other passage making vessels for comparison, we found helpful information posted online by several experienced Nordhavn owners which we have noted below. If anyone has data on other types of passage making vessels, we would love to see it. From what we gather, a significant percentage of Nordhavn owners care about accurate data as much as we do.

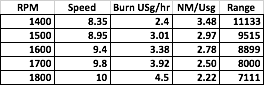

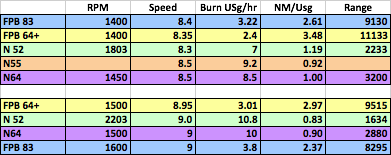

Note that this data is for a lightly loaded configuration without auxiliary loads. It is comparable to the data which follows. In digging up fuel burn data on other passage making vessels for comparison, we found helpful information posted online by several experienced Nordhavn owners which we have noted below. If anyone has data on other types of passage making vessels, we would love to see it. From what we gather, a significant percentage of Nordhavn owners care about accurate data as much as we do.  The data set above is for a Nordhavn 52 (you can see the details here). With the trawler types there are big gains in range to be had from going slower. Next, data on a Nordhavn 47 and 55.

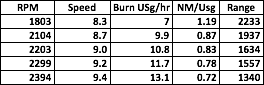

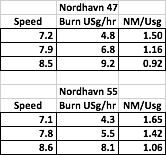

The data set above is for a Nordhavn 52 (you can see the details here). With the trawler types there are big gains in range to be had from going slower. Next, data on a Nordhavn 47 and 55.  This data is from the Yahoo Nordhavn Dreamers Group (available here). Next are some numbers from a Nordhavn 64. This is from the MTU diesel CPU, at full displacement, in calm conditions.

This data is from the Yahoo Nordhavn Dreamers Group (available here). Next are some numbers from a Nordhavn 64. This is from the MTU diesel CPU, at full displacement, in calm conditions.  The owner of the yacht mentioned above did a 1000+ mile passage, running at 1525RPM, for an average passage speed of 8.68 knots. Fuel burn was .9 nautical miles per gallon in calm conditions. In addition, the genset ran 24 hours a day consuming an additional gallon per hour. It bears repeating that none of the above data, except for Wind Horse, contains an allowance for genset consumption or rough water drag. In addition, were these yachts loaded for a long cruise, their fuel burn would increase. Next, a comparison table.

The owner of the yacht mentioned above did a 1000+ mile passage, running at 1525RPM, for an average passage speed of 8.68 knots. Fuel burn was .9 nautical miles per gallon in calm conditions. In addition, the genset ran 24 hours a day consuming an additional gallon per hour. It bears repeating that none of the above data, except for Wind Horse, contains an allowance for genset consumption or rough water drag. In addition, were these yachts loaded for a long cruise, their fuel burn would increase. Next, a comparison table.  In this case we have tried to pick speeds that were close between the boats. The Wind Horse (FPB 83) numbers are skewed by the inclusion of an auxiliary load factor and her being at full displacement. In conditions comparable to the other yachts her data would be 15/20% better. Now the most difficult issue, safety factor. Just how much margin for the unforeseen is enough? Your approach should vary with the risk factors from weather, and reliability (or lack thereof) of fuel on the other end. We want so see at least a 25% margin. This allows for adverse weather, and mistakes in fuel measurements and consumption calculations. Our preference, however, is for the 25% plus sufficient fuel to get us to an alternate refueling location. In periods when there are fuel supply disruption risks the margin we want goes up. This is one of the reasons the FPBs have such enormous range. What do you do if you are light on the factors of safety? Slow down, get better mileage, and be less comfortable. The weather risks go up, but for in season trade wind routes these may be acceptable. On the other hand, if you are headed across the North Atlantic, you have to assume at least one good blow, possibly more, will be encountered. The more you slow down, the greater the weather risk. The same applies to passages like Fiji to New Zealand, or Bermuda to the Eastern Seaboard of the US. So, be prepared. A final word on determining consumption. The safest way to do this is to fill a tank, make a passage on it, refill, and divide by hours run (hopefully at constant speed). The next best approach, if you have an accurate sight gauge on your day tank, is to run several miles up, and back (to cancel out wind and current impact) and the note the sight gauge (measurements should always be done when it is calm). The longer the runs, the more accurate the data. Engine CPUs, like those supplied by John Deere will in theory get you close, but we would allow for a ten percent error. You can also run fuel from a small barrel, and note the consumption in different conditions.

In this case we have tried to pick speeds that were close between the boats. The Wind Horse (FPB 83) numbers are skewed by the inclusion of an auxiliary load factor and her being at full displacement. In conditions comparable to the other yachts her data would be 15/20% better. Now the most difficult issue, safety factor. Just how much margin for the unforeseen is enough? Your approach should vary with the risk factors from weather, and reliability (or lack thereof) of fuel on the other end. We want so see at least a 25% margin. This allows for adverse weather, and mistakes in fuel measurements and consumption calculations. Our preference, however, is for the 25% plus sufficient fuel to get us to an alternate refueling location. In periods when there are fuel supply disruption risks the margin we want goes up. This is one of the reasons the FPBs have such enormous range. What do you do if you are light on the factors of safety? Slow down, get better mileage, and be less comfortable. The weather risks go up, but for in season trade wind routes these may be acceptable. On the other hand, if you are headed across the North Atlantic, you have to assume at least one good blow, possibly more, will be encountered. The more you slow down, the greater the weather risk. The same applies to passages like Fiji to New Zealand, or Bermuda to the Eastern Seaboard of the US. So, be prepared. A final word on determining consumption. The safest way to do this is to fill a tank, make a passage on it, refill, and divide by hours run (hopefully at constant speed). The next best approach, if you have an accurate sight gauge on your day tank, is to run several miles up, and back (to cancel out wind and current impact) and the note the sight gauge (measurements should always be done when it is calm). The longer the runs, the more accurate the data. Engine CPUs, like those supplied by John Deere will in theory get you close, but we would allow for a ten percent error. You can also run fuel from a small barrel, and note the consumption in different conditions.

February 12th, 2011 at 4:56 pm

Hi Steve,

Is there a website that publishes fuel prices at ports from around the world?

February 12th, 2011 at 8:30 pm

Howdy Max:

We usually Google diesel fuel price in whatever region we are in and something pops up. Perhaps a SetSail visitor will have a suggestion?

February 12th, 2011 at 5:13 pm

Explanations (?):

“The full load displacements are as follows:

FPB 64 – 88,000 lbs/40,000 kg

FPB 83 – 92,000 lbs/41,700 kg

FPB 112 – 165,000 lbs/74,800 kg”

N64: Displacement: 185,000 lbs.

N55: Displacement: 115,000 lbs.

N52: Displacement: 90,000 lbs. (this is getting closer)

And if you somebody wants to contrast it with an older design:

Egret – N46 – they concluded their circumnavigation after a couple of years yesterday (with recent fuel figures) running at about 6.1 knots: http://www.nordhavn.com/egret/captains_log_feb11.php

N46: Displacement: 60,000 lbs. / 27.22 T

“3.14nm per U.S. Gallon range or .826nm/liter”

Hubert

February 13th, 2011 at 12:03 pm

I think you are not comparing similar things here. When you compare fuel consumption data you should at least compare similar hull dessigns. Comparing a deep draft, high D/L vessel derived from fishing trawlers to a shallow draft low D/L canoe (of different dimensions),is like comparing apples and oranges. Moreover the amount and quality of data provided are insufficient for any real, methodical and scientiffic comparison. Nevertheless I read all of you books and I follow you blog as I find it very informative and interesting.

February 13th, 2011 at 6:35 pm

Hi Nicolas:

The data presented is not intended for comparison, but just to give an idea of speed, economy, and range. We’d love to do a more thorough presentation, but getting accurate data is almost impossible, and there are time constraints as well. That said, in terms of efficiency in crossing oceans there should be plenty of info for folks to draw their own conclusions, if warranted.

March 16th, 2011 at 1:28 pm

Hi Steve,

I thought you might be interested in some figures from the 62ft / 19 metre Nigel Iren’s designed motorboat “Molly Ban”. She is an example of his thinking on long waterplane, displacement hulls; she is GRP, about 20 tonnes fully laden, with a single Cummins 305hp driving a conventional prop. I see numerous similarities between her and your concept, albeit Molly is more a coastal cruiser than a trans-oceanic yacht. She’s been in commission since May 2008 in the Irish Sea, English Channel and the Baltic, and her real world performance figures have been very consistent with the predictions.

Her top speed is about 18 knots but the concept was always to have an economic cruise well below that. We thought about 13-14 knots would be about right, although he owner often prefers to come right back to 10 to 12. At 10 knots she uses 10 litres an hour in flat water(about 2.64 US gallons); at 7 knots she uses just 1 USG. Obviously at the upper end of the speed range things change; at 13 knots (2000 rpm), she is using 7.1 USG; flat out, at 18 knots, she uses about 14.5 USG.

Yours,

Theo Rye.

March 16th, 2011 at 2:38 pm

Thanks for the data, Theo:

I have been an admirer of Nigel’s work for many years.