We are standing at the forward end of the great room aboard FPB 78-1 Cochise. It is eerily quiet as we watch the steam gauge climb from 13 to 20 knots, linger for a moment, before peaking at 22. A fast-rising SE gale has kicked up a steep sea, now confused with a reflected crossing wave pattern as we rapidly close with the Southern entrance to New Zealand’s Bay of Islands. This 60 metric ton motor yacht is surfing under autopilot control. The seas are perfect for Cochise and she rides the better waves for several minutes at a time, at speed length ratios above 1.6. Cochise is the most recent iteration of the perfect yacht, at least for us. Aboard Cochise, and the rest of our yachts, the key design ingredient upon which all else rests is steering control. We are warm, dry, and very comfortable.

It wasn’t always so.

Linda, my partner in all things, is laughing about how times have changed. We met on a fateful Labor day weekend in 1965, when Linda, then teaching in Salt Lake City, Utah, made a spur of the moment visit to her sister in Malibu, CA.

As it turns out Sonnie and her husband Charles were planning on spending the long weekend at Catalina with our family aboard my folks’ Hu Ka Makani, a 58’ cruising cat. I had sailed my 20’ Shark catamaran over with Charles.

Above: Linda, left, with Sonnie that fateful weekend.

Linda went for a sail with me on Beowulf, and it was obvious that, even though a “mountain girl”, she was a natural. It was Sunday morning when Linda and I took a walk from Cat Harbor to the Isthmus, and then hiked up the trail towards Fourth of July cove. Along the way our hands brushed, and then fingers entwined, and the sparks flew. It has been ever thus. We decided to sail back to Marina del Rey together on my little cat, but fate intervened in the form of her older sister and my step mother, and I was left to bring Beowulf back with Charles.

Linda came down from Salt Lake for Thanksgiving and we entered the Cabrillo Beach Yacht Club Turkey Day Regatta. We rounded the weather mark well ahead in the Cat Portsmouth handicap class, but alas my mind was not totally on the race details, and we took the weather mark to starboard rather than port as called for in the sailing directions. The entire fleet followed us around the wrong way except for the very last boat. That left us with a DSQ and two firsts, and a second place trophy, very embarrassing.

Fast forward to the next summer, Linda has moved to LA, and we are now driving to Charleston, SC for the Shark Catamaran National Championships. The plan had been arrive a week early, check out the local knowledge – the race course is where two rivers come together around the island on which sits Fort Sumter – but business had kept my nose to the grindstone. In those days we built large fiberglass displays for various businesses. Linda, above, is modeling a 12-foot Sinclair dinosaur. This was the only stop we made other than for gas, potty breaks, and one short rest. We barely made the start of the first race.

This is Linda’s first serious regatta. Her crew work is so good that observers comment on how we seem to gain on every tack, jibe, and mark rounding. Halfway through the regatta we are allowed to haul our boats to clean and work on them. We’re last out as we’d been doing a bit of sail testing. There are a few competitors watching and chit chatting prior to the annual class dinner. One of them asks how we’d met and I reply that Linda had been hitchhiking in Texas and as I needed crew I picked her up. Being the olden days, before sin and corruption was widespread, there is somewhat of a scandal – or maybe it was envy – surrounding our sleeping arrangements. Word flies about that we are sharing a room. This was the truth, as being on a budget we needed to conserve. By the time we reach the dinner, the hitchhiking story has spread.

No doubt the discombobulation that follows on the race course behind us is due in no small way to the other sailors’ envy. We win easily, and I quickly recognize that if I don’t marry this talented crew someone will steal her away.

We need to stop here for a moment and give props to a man who directly had a major impact on our life at several critical junctures. Swede Johnson was Saint Cicero’s number one sailmaker at Baxter and Cicero. It was Swede who had made the sails for our second Shark. Since the Shark was overweight, which we did not realize at the time, Swede’s sails were the major reason for our boat speed and victories.

The boats on which we raced in those days were wet, usually cold, and did I mention wet? On a beautiful calm morning we would trudge down the dock wearing full foul weather gear, boots, and trapeze harnesses. Linda did not know any other way existed. We avoided the contamination of comfortable boats.

Here’s a shot of one of our C-class cats, this one Beowulf III. She was a much more “comfortable” boat and quicker too. Notice how the lee bow is fully immersed in spite of our weight being all the way aft. This locked in the bow and made steering response to changes in apparent wind force and angle problematic. But everyone had this issue and we accepted it.

Wing masts were now de rigueur in the C class, and not wanting to deal with the handling negatives we opted for something different for Beowulf IV. She had an 8” diameter light aluminum tube for a mast, with a pair of awning tracks riveted tangentially, to each of which was affixed a mainsail. If this sounds familiar, the 36th America’s Cup is using a twin luff mainsail. Beowulf IV had canted lifting 65 series laminar dagger boards and was very light, just a single skin of six-ounce boat cloth over 1/4″ end grain balsa core for hulls, with chemically milled aluminum cross beams. When everything was in the groove she showed flashes of real pace. We were invited to the Yachting Magazine one of a kind regatta on Lake Michigan, and Linda being seven months pregnant, we decided that I would take another C-Class sailor, Dave Bradley, as crew.

Competitors had begun to arrive the week before the regatta. It was fun eyeing the other class champions and all-star sailors. Between testing, chatting, and checking race course conditions there was a lot going on. First race was Monday following the skippers meeting.

Sunday evening, just before dark, in rolled a massive A scow. The crew quickly stepped the rotating mast, towed out to a mooring, then retired to the bar. If this was meant to intimidate the opposition, it worked with us.

In the first race a wind shift favored the leeward end of the line. We were perfectly placed, reaching down the line for the start except for the 38’ A scow on our hip. This was the machine that was then considered the fastest sailboat on the planet, and we expected them to roll over us after the start. With the leeward end favored we were going to need to tack to port ASAP to cross the fleet and lock in our initial gain when the wind shifted back. If the scow was close enough on our hip to hold us, we would be sucking gas from a large chunk of the fleet.

The slapping sound of that scow close by still rings in my ears when I think back.

We hardened up after the gun working the double sail main carefully as high as we could, trying to pinch off the scow. Dave was adjusting mainsail twist in the oscillating breeze. I was driving, watching the waves, concentrating on the shift we knew was coming.

After a couple of minutes Dave said, “I don’t hear them.”

“Have they tacked?”

“No. They are four boats back and dropping into our wind shadow.”

We were first to the weather mark with the 32’ D class Wild Wind close behind. Wild Wind did a number on us downwind with her spinnaker and we ended up second. The scow came 4th, with the new Olympic class cat Tornado ahead of them.

The next day a norther was blowing. On the way to the start we broke a daggerboard and decided to try and pick up a spare before the race started. We were running almost square into the Belmont Shores harbor entrance, main fully stalled, when a shift hit us, we accelerated, and the bow depressed. With the steering locked in by the bow and rig powered up in the steep seas reflecting back from the shore, a pitchpole was inevitable. Dave and I were okay as was the boat, but in the ensuing rescue attempt Beowulf IV’s rig went to the bottom along with much of the rest. My main concern was Linda’s reaction. I was afraid she would go into labor.

With a family started, we decided to try something smaller and more easily managed by the two of us. We chartered a an old Tornado cat and went to play in the first World championships held in Melbourne, Florida. Linda and Elyse managed base camp and Steve Harvey crewed. We were nowhere near as good as when Linda was aboard, and managed only a third overall in the tune-up regatta and tenth in the Worlds (I dislike light air).

Neither of us were inclined towards giving up our joint approach to racing, but now with Elyse on the scene we started thinking about the perfect boat for our new station in life.

Enter Beowulf V, our first family cruiser. If you know any C-Class cat sailors you know they have garages full of boat parts. Masts, sails, dagger boards, rudders, even cross beams. We fell into that category, which allowed us to play “Frankenstein” with our new ideas.

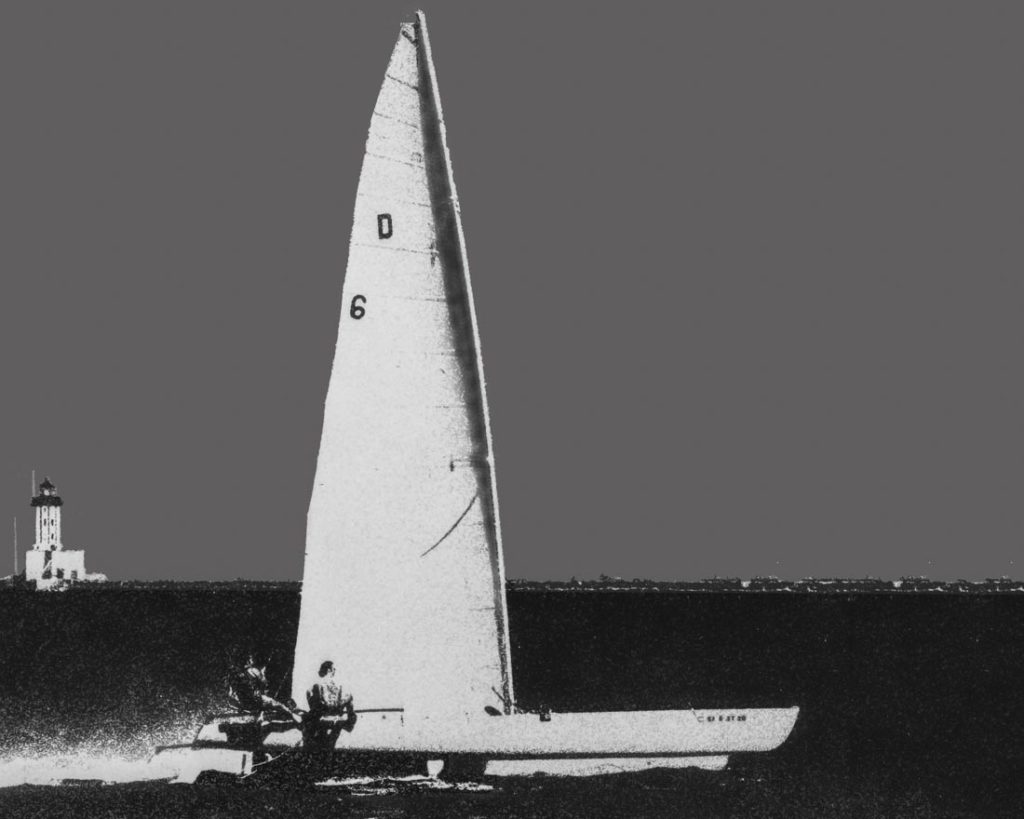

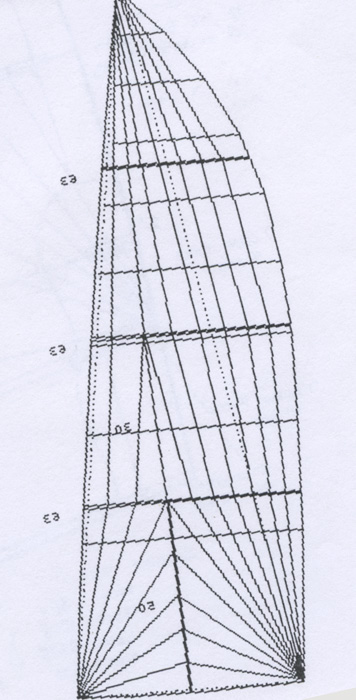

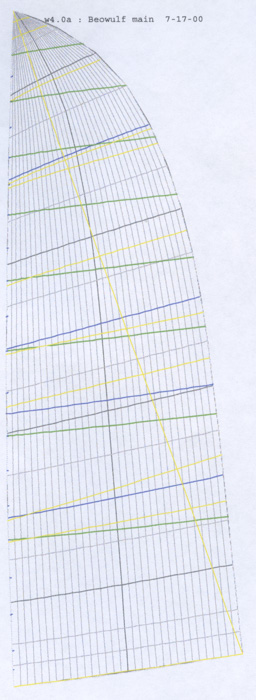

A friend in nearby Venice, California, Skip Hawley, was building the new Tornado cats using the tortured ply method. We looked at the system, and decided to do something a little longer. Skip added 12 feet to his deck jig, we called Gordon Plywood in Los Angeles and ordered 12 sheets of unbalanced 3/16” aircraft grade spruce ply, and soon thereafter Beowulf V was winning local regattas and setting records. The main in this photo turned out to be by far our fastest. It was a left over C class sail, just 300 square feet (D class cats could carry 500 square feet).

Check out the wind strength above. The wind sock on the committee boat is hanging. There are no whitecaps. It is blowing eight knots. We are at a true wind angle of about 135 degrees. The apparent wind is so far forward the reacher is being flown to leeward! Notice how the mainsail is sealed to the trampoline, creating an endplate, resulting in a significant boost in performance. These hulls weighed 152 and 154 pounds each. All up Beowulf V tipped the scale at 702 pounds.

Here we are holding the Victor Tchetchet perpetual “World Multihull Championship” trophy. There are five Beowulf plaques attached thereon.

This 32’ D-class “mongrel”, totally created from castoffs except for the hulls, turned out to be a rocket. During a Pacific Multihull speed trial in 1971 Beowulf V was timed over 500 meters, averaging 30.95 mph. She later pushed this to 35.6 mph, good enough for the Guinness book of records and the New York Times yachting column to think she was the fastest of all.

In smooth water and stable wind pressure Beowulf V could bootstrap herself with apparent wind until she ran out of steering control. As the wind pressure increased the lee bow would depress, and Beowulf V would lock in. At this point you better be pointing in the correct direction. The helmsman had to anticipate the puffs and pull the bow downwind or up prior to an increase in wind force.

If you were late, the only avenue for reducing heeling force was easing sheets. When you are sailing at 1.5 times true wind speed the slightest error – and this included easing sheets – would quickly cut speed in half or more.

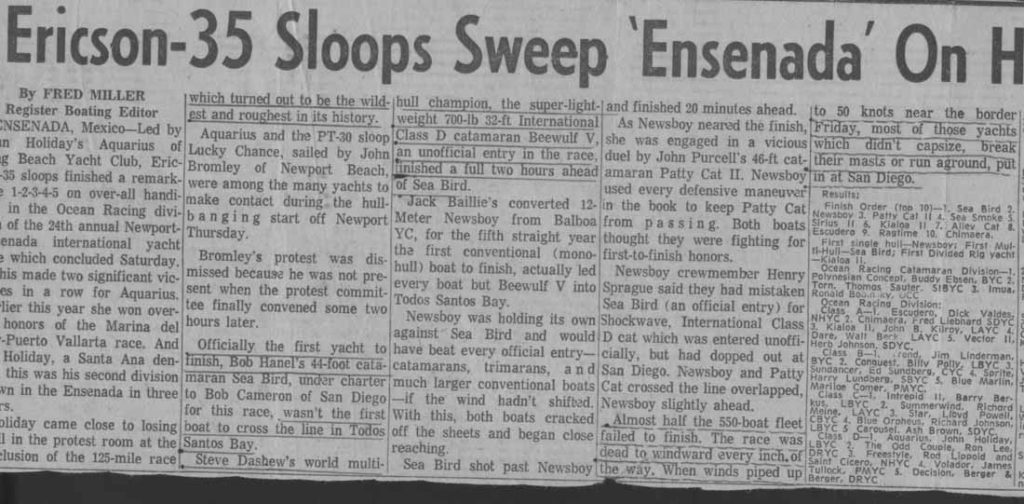

One more Beowulf V story. We were headed to Ensenada, above, during the annual D-Class cat cruise to Mexico. (That this happened over Cinco de Mayo weekend and coincided with the Ensenada race, then the largest yacht race on the planet, was purely a scheduling coincidence. The catamaran powers-that-be had said we were not safe and we would not be allowed to play.) This particular year, a front came through. It caught us as we were in light airs working the back wind of the beach break, about 40 miles north of the finish. It was pitch black, we had no sea room, the coast to leeward was iron bound, capsize had a terminal connotation, and we were close to finding out what the the term scared shitless meant, for real.

We stayed upright by feathering into the breeze. We could not even see waves, let alone the horizon. We knew when the weather hull was flying because the long tiller would drag in the water to leeward and the driver would know to push, bringing the bow into the wind.

The front passed, we finished the course, and went to sleep. I had sailed down with our friend and sailmaker Ric Taylor. By the time we’d eaten breakfast Ric and I had decided it hadn’t been such a big deal. As the fleet began to straggle in though, we saw numerous damaged sails, spreaders with kelp trailing, and in the Bajia Hotel bar some very haggard faces. Fred Miller’s story from the Orange County Register is scanned above.

A current photo of Beowulf V above, now in its 50th year, and still winning races in the San Francisco Bay area under the careful hand of Alan O’Driscoll.

With Elyse now joined by Sarah, we got to thinking about a family cruiser with more creature comfort. None of our previous boats had been “designed”, rather they had evolved. But what if we could control the hull shape in such a way as to reduce or eliminate the bow depressing as we picked up speed? Then we could steer more easily, which could make a whole new world possible.

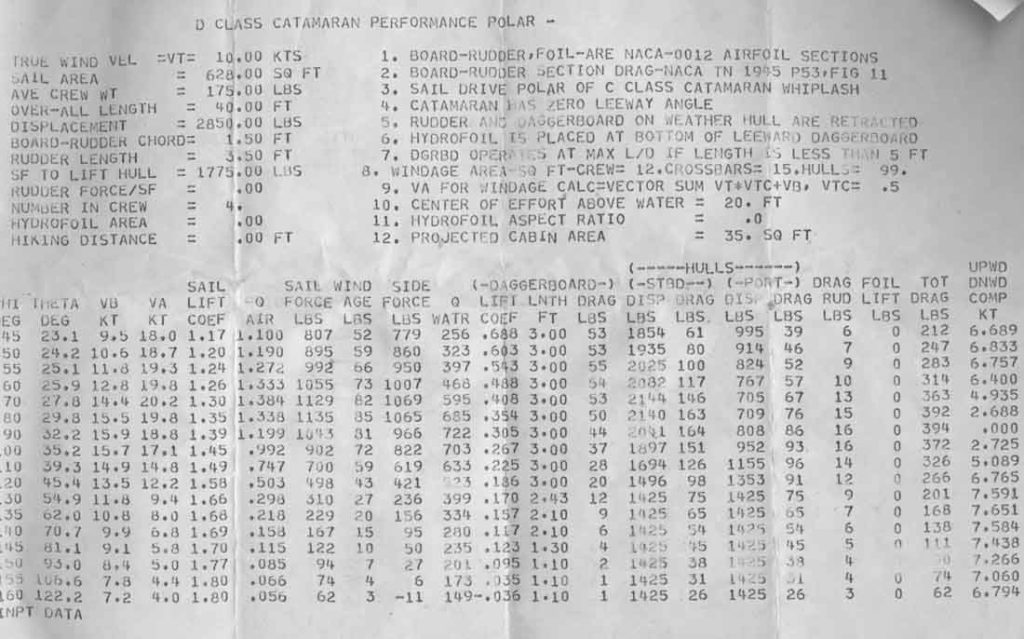

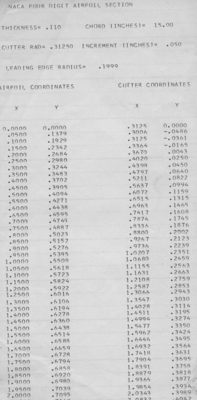

Norm Riise, a sailing competitor and often crew, whose day job was designing solar simulators and hypersonic wind tunnels at Cal Tech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratories, had a potential answer. This self-taught engineer, a one-time torpedo bomber pilot in the Pacific during WWII, was working on the very first yacht performance prediction program. Norm ran his code from punch cards on the JPL main frame computer at night, when time was available. We’d helped Norm tune his VPP by giving an opinion on various computed scenarios. Norm felt he was far enough along that we should give it a try.

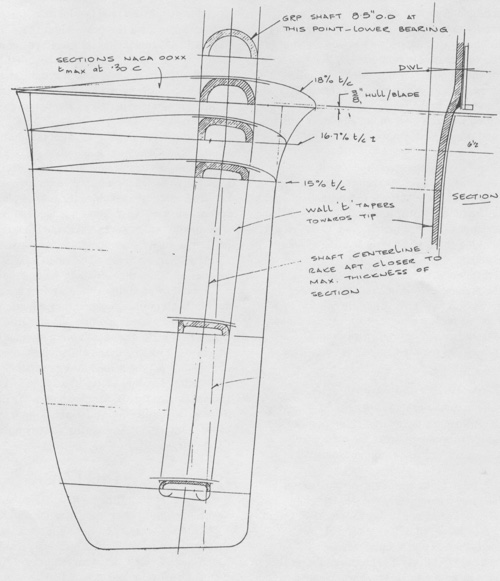

Norm’s software allowed us to do a detailed parametric analysis of what would become Beowulf VI. We would vary hull prismatic, percentage of displacement, dagger board design, while investigating length, mass, percentage of total mass carried on each hull, and of course various rig permutations.

This was an early concept that we did not use, but the only example we can find…from 45 years ago.

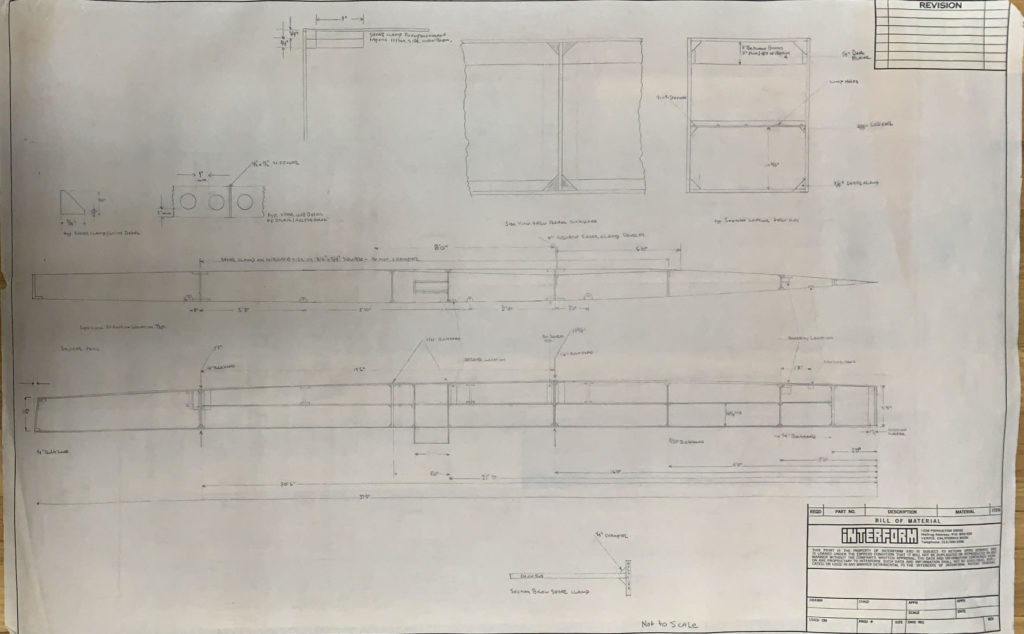

Here is a cutting table for making a foil template.

And one of the construction drawings. The hulls were a simple box, with rounded foam sections glued to the bottom.

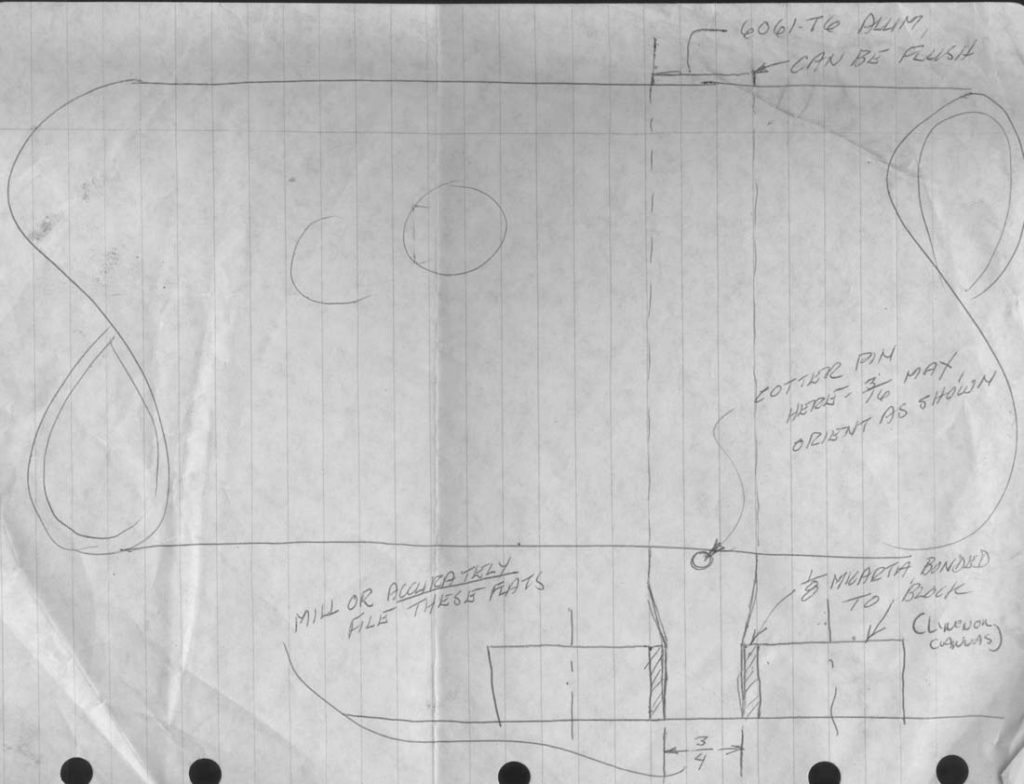

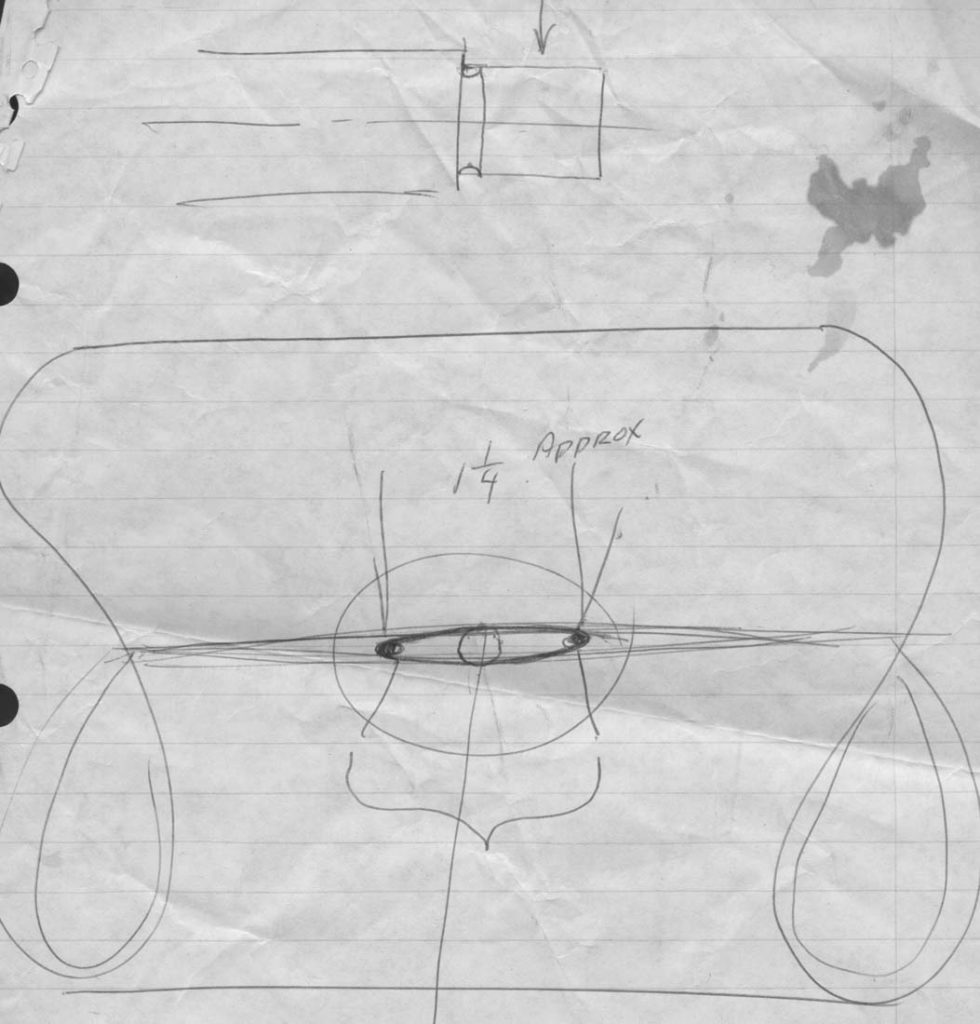

XXX One of the ongoing structural problems of this era was the connection of the beams which held the two hulls together to the hulls themselves. With typical cat hulls, those with unbalanced lines that split the displacement between the hulls, once you began to fly a hull, or were driving hard downwind, the bows would depress. The only thing you could do was move the crew weight aft. In order to transmit the righting moment of the crew to the leeward hull the cross beams had to resist twist. Therefor the cross beams had to be rigidly installed. The bending loads combined with the twist created complex stresses which were not easily dissipated. But with full displacement hulls that maintained a constant center of buoyancy as more load came onto them, the tendency to drive the bow under was eliminated. So the cross beams no longer had to transmit aft moments from crew weight to try and hold the bow up.

All of which lead to the method shown above of connecting the beams. The beams are round, and the connection system did not try and hold the hulls firmly in a torsionl mode. Rather, the hulls were free to rotate around the round beams. A very savvy engineer, Gerry Magarian, came up with the concept of using a pin which ran in a slot that kept the beams in place on the hulls, so they could not slide in or out on the beams, but allowed the beams to rotate.

The system worked well, and allowing the hulls to flex had motion benefits. Removing the twisting torque allowed us to reduce the strength and weight of the beams.

XXX The beams were carefully engineered with areas of chemically milled tapering pf wall thickness. One evening after a hard day at the office was getting ready to drill and tap the holes which would attache the tangs for the dolphin striker stay.Lack of attention lead to a hole being drilled in the wrong spot. Round holes are stress risers, and this one would have reduced the local strength by 500%.The beam was saved by carefully creating this elongated oval around the errant hole. The oval reduced then stress concentration almost entirely.

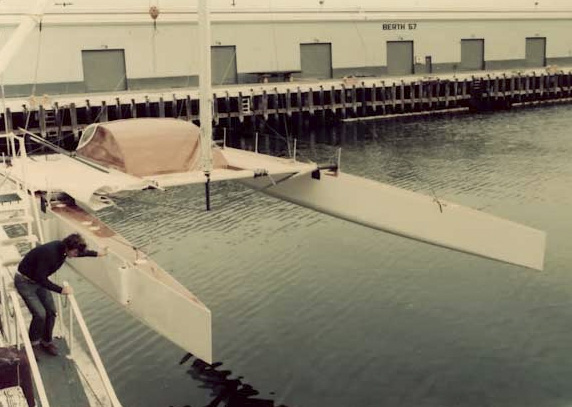

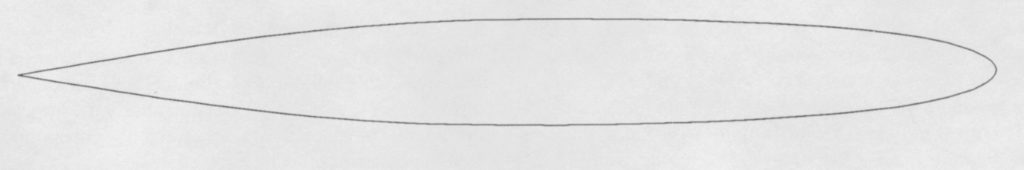

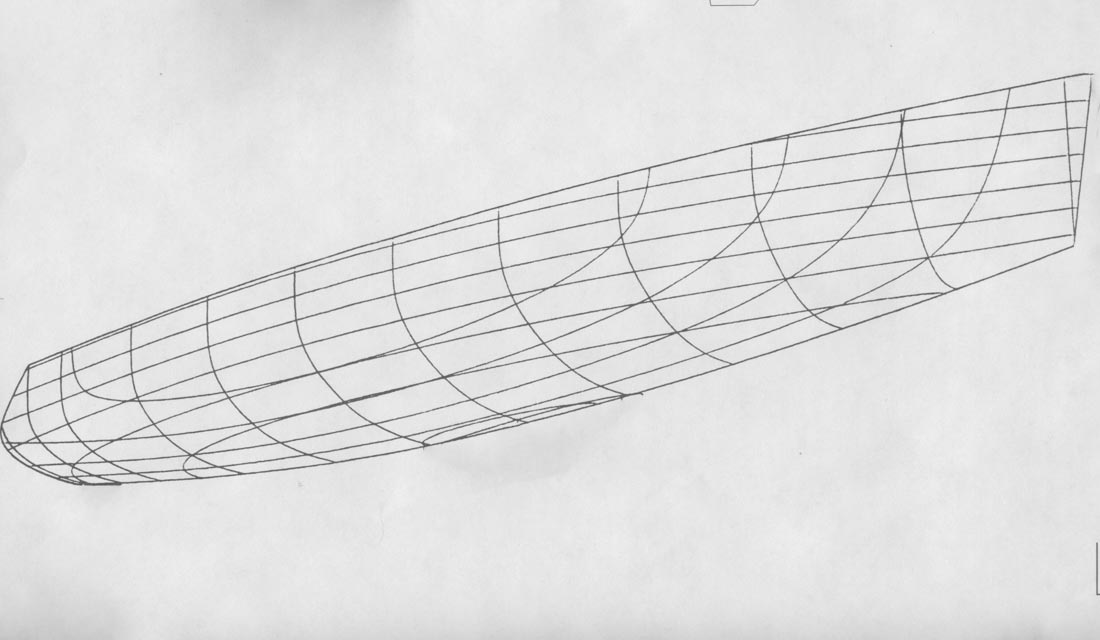

We quickly learned that there were enormous wetted surface benefits to sailing on a single hull optimized to carry the full mass of the boat. Beyond this the design basically boiled down to build the longest, lightest hull practical, reducing displacement length ratio to where wave drag was negligible at all speed length ratios, after which the goal was minimizing wetted surface.

Beowulf VI ended up with 37’ long hulls that were 19” wide, and had just 21” of freeboard forward. Because she had full displacement hulls that were exceptionally narrow, she was designed to penetrate waves rather than riding over when pressed going to windward or close reaching.

The hull box structure was made up of a deck, a mid-height horizontal shear web, and a flat bottom that represented the waterline. All three were exactly the same shape. Onto this bottom were glued a series of 4” thick semicircular structural foam sections. Mickey Muñoz, one of the world’s preeminent surfboard shapers, spent a weekend smoothing things down, after which we applied two layers of 6-ounce boat cloth. Each hull, with hardware attached, weighed 375 pounds. The entire boat, with full required gear for offshore racing but before crew, was 1,770 pounds hanging from a single point scale. With a crew of four, the displacement length ratio was 18.

Without a great deal of effort on the part of the helmsman she could maintain an easy 1.6 times wind speed–up to 1.95 in perfect conditions–until 26 knots of boat speed, after which the sea state forced us to back off. The key to all of this was steering ability, and the secret to steering was a hull that did not depress its bow. This photo, taken by Mary Edwards during the 1974 Ensenada Race, has Beowulf VI moving at 20+ knots in 16-18 knots of breeze. The ORCA fleet is already hull down on the horizon behind us. Aboard are Norm Riise who you can see in the yellow slicker, John Rousmaniere, then West Coast editor for Yachting Magazine, and Ric Taylor.

Beowulf VI had sufficient buoyancy in each hull to carry the boat’s full mass. Driving hard on one hull was not a problem because the bow did not depress, as you can see in the photo above. These slim, full buoyancy hulls were like knives and would slice right through the chop going to weather. The lee hull could be driven through steeper waves with little sensation of deceleration.

Her little cabin, six and a half feet square, had two bunks, a porta potty, stove, and ice box. All the comforts of home. She would fly a hull in seven knots of breeze – we never cleated anything – and was a great cruising boat according to our ideas on the subject at that point. We would sail to Catalina for a hamburger with our two daughters, then aged two and five. Yes, we were a little crazy, in retrospect.

Elyse, at five, is demonstrating the cozy confines of the forward half of the “great room” aboard Beowulf VI. Note the needlepoint pillow. Fancy interior decor.

During this period, our first paid design gig came about somewhat accidentally. Hobie Alter was a long time friend when he showed up at a 1967 Pacific Multihull Association championship regatta with his Hobie 14. This slow talking surfer dude was one the sharpest minds we have ever known, although for the most part he kept that under wraps. As a surfboard maven Hobie was at the top. But his technical expertise in regard to cat design was lacking, or so we and all the other “experts” on that subject agreed.

But it turns out the H14 had some design features that nobody had thought of before. It was optimized for beach launching as opposed to crane hoists or launching ramps. Hobie’s and our paths crossed from time to time but we had more interaction with Mickey Muñoz and Phil Edwards who were surfer/sailors par excellence. Both were better known for their big wave riding and were, or I should say are, legendary in the surfing world. Phil worked full-time with Hobie in the R&D department at the Hobie cat company, Mickey more occasionally. We often raced against each other in our respective catamarans.

In 1969 Hobie was at the Yachting OOAK regatta where we lost Beowulf IV. Hobie and his little 14-footer and the mighty 32-foot Wild Wind were the only finishers in that windy norther. A double-page photo of Hobie literally airborne appeared in Life magazine with the caption “Hobie – The Cat That Flies” and they were off to the big time.

Art Hendricksen was Hobie’s partner. Smooth talking, a Stanford graduate, Art thought he was business savvy compared to Hobie and didn’t mind letting you know it. As the business grew they hired a day-to-day president. By 1974 Hobie and Art were not speaking. Hobie was focused on projects that were not on Art’s wish list.

I got a call one day and was asked if I could do a new boat for them. I responded in the affirmative, but only if Hobie approved and was involved.

Hobie 18 drawing, above.

We agreed on a fee and I drove down to Dana Point to meet with Hobie, Phil and Bud Platt. We sailed the 16s a bit, in and out of the surf, and up the beach. We chatted, scribbled some sketches, and then drove to the factory to see the boats being built.

A week later I had the design finished, sent it off and within a month they had three sets of hulls floating on which to test rig configurations. Thus was borne the first paid design of our career. That the Hobie 18 was a commercial success was due mainly to the real world practical know-how and configuration testing of Hobie, and his R&D crew.

Back on Beowulf VI, after being allowed to officially enter the Newport to Ensenada race, as an entrant but not a contestant, and breaking the long standing Aikane elapsed time record in the process, Linda and I had a leisurely cruise back up the coast. (Beowulf VI, above, is rafted with Micky and Peggy Muñoz’s Malia at Todos Santos Island off Ensenada). We enjoyed the cruising so much that we started thinking about doing more of it. ORCA’s twisted handling of our entry, the result of trying to keep the prestigious first to finish trophies for the establishment catamarans, had lead to embarrassment when the press – John Rousmaniere among them – had tried to untangle our status. ORCA instructed us we must apologize to the board of directors for this problem, which we politely declined to do. We were thereafter banned from racing in the offshore venues which they controlled. I was depressed, Linda was, well, pissed. Beowulf VI had been built to break records and now we had nowhere to officially play. We weren’t sure what to do next.

And now a little background on how we’d gotten to this point…In the olden days before we were married I had a great little business called International Fiberglass, making giant fiberglass figures.

I had gotten into this almost as an accident. In an effort to smooth out the work flow in my tiny yacht maintenance facility in San Pedro I had “designed” a 14-foot outboard powered ski boat, a compact version of the flat bottomed drag race and ski race inboards popular on the Colorado River. The learning curve had been exceptionally steep. After the careful and expensive creation of a mockup or plug, as it was called, I had hired two fiberglass “experts” to help us make a hull and deck mold. Except that my experts forgot to use mold release, and we ended up removing the plug from the mold with steel wedges and sledge hammers. You might say that the Incomparable Eliminator, as we modestly named this vessel, had been through a difficult birth. (This was the first of several near death business experiences.)

We finally figured out the mold making process, sold a few boats, and moved away from yacht maintenance. One afternoon I got a call from my Dad, who had seen an advertisement in the classified section of the Los Angeles Times he thought might interest me. There was a fellow named Bob Prewitt who built horse trailers, and had a sideline of making fiberglass displays as a fill-in for his laminating crew when they weren’t making parts for his horse trailers. Prewitt was an old cowboy, seriously into the rodeo competition circuit, and wanted time now to concentrate his efforts.

His molding process was centered around the use of Jay Johnson’s fiberglass “chopper” guns. We had used several of Jay’s prototype chopper guns for bonding in plywood reinforcements in our Eliminators. I made a deal with Prewitt and was suddenly in the display business.

We were making a few fiberglass figures, selling a ski boat now and then, and growing slowly but steadily. Then one afternoon the mail brought a new issue of a trade magazine aimed at gas station operators. On the front page was a photograph of our Paul Bunyan, standing in front of an American Oil gas station, with a headline declaring that Larry Smith’s AMOCO station had doubled the gallons of gasoline sold in the week following Mr. Bunyan’s arrival.

Violet Winslow, “Granny Vi” as she was known to our kids, joined our team to promote this giant display business.

Our 20-foot tall Paul Bunyans were best sellers. Derivations of Paul became the center of marketing programs for oil and tire companies like Texaco, Phillips, Standard Oil, Uniroyal, to name a few.

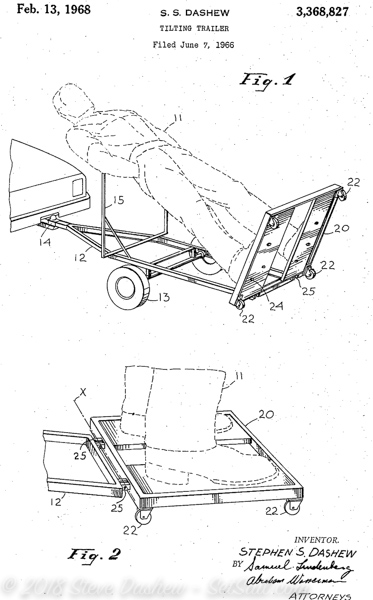

A key part of the success of these programs was the ability of local marketing reps to move the figures between retailers. The sketch above is of our first patent of a tilting trailer that made this possible.

It was the era of the Mustang, Humble Oil Tiger, and the Sinclair dinosaur. This wonderful, fun, and profitable business had resulted from trying to find something to keep my little boat business working in the winter. (For a more detailed look at what we produced in those days check out RoadsideAmerica.com.)

I was traveling constantly, which was fun. But once Linda moved to LA the travel lost its allure. We took our fiberglass “technology” into the construction business looking for a more conventional business model that did not require constant travel. Hubris combined with inexperience is not a good combination in the rough and tumble world of US commercial construction.

Married now, and not knowing how to quit, we persevered. Eventually we dug ourselves out of a very deep hole and we learned quickly. Inexperience did have one big advantage–we did not know what we could not do. That allowed us to see inefficiencies in concrete forming methods others had missed, precisely because we were not blinded by training.

Formal education had been a waste for me. In high school and college I did not have the required discipline to study anything I considered boring. Sailing, surfing, hot rods, and the fairer sex were what held my attention and where my energy flowed. The one thing I had learned in school was how to ask questions, a skill used whenever possible to embarrass whomever it was standing at the head of the room. A pain in the ass student? Definitely.

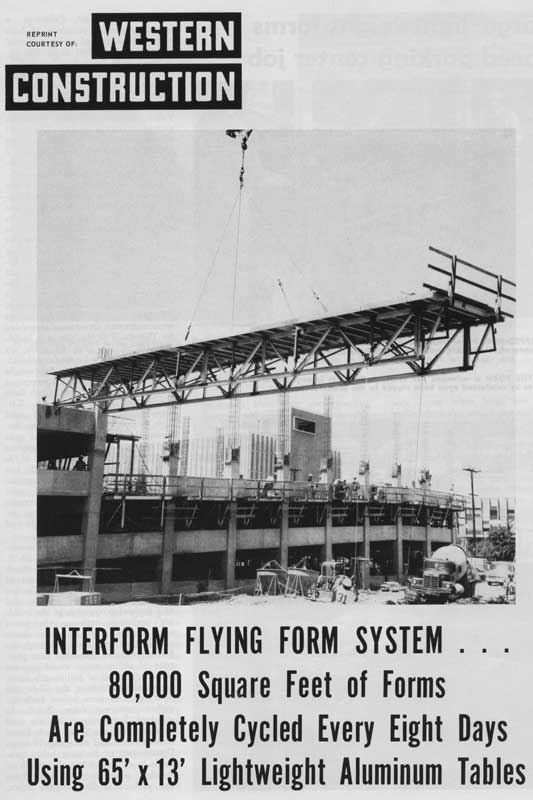

This impudent behavioral streak combined itself with a disposition that hated to lose. In the construction business it lead to the development of something called the “flying form”. In a normal business cycle in the construction industry these patented labor saving forms would have been a historical footnote. But in the late 1960s, with REITS booming and a tight labor supply, there was a brief opening to penetrate the market. We were moving as much as 1,200 square feet of formwork at a time, often with pan or waffle forms attached, occasionally even with spandrel forms integrated. Give us a tower crane for a couple of days a cycle and we could reduce labor force by 80%, move at a much faster pace, and eventually reduce material weight and cost with proprietary structural designs.

Our background in fiberglass led us to take on some technically difficult contracts. The most challenging of these were the concrete forms used to build the outer columns and waffle slab soffits for the Hirshborn Museum in Washington, DC. (Your authors above five decades later.)

By the time the market began to cool and the major subcontractors came gunning for us we were established with large inventories of our own, superior system.

Growth was rapid, profitability good, and capital requirements significant. But aggressive expansion on my part left us vulnerable. One day I awoke to the realization of just how shaky things were. That this occurred concurrent with an increase in interest rates, an industry wide slowdown, and the gods of Ocean Racing Catamarans banning us, lead to an epiphany. Between having lost our official playground with ORCA, and grown tired of the long hours and constant battle of our little enterprise, a sudden decision came upon us. Let’s sell the business, buy a boat, and go cruising. Timing was not good but Patent Scaffolding wanted our inventory and portfolio of patents. They took us off the hook at the bank, paid enough so that our investors got out okay. We had to stick around for a while, and sign a five year non-compete agreement, but after that we were free! The decision to sell at a low point of the business cycle had not been easy. But we were young, and had ideas of what we wanted to do next. Although our financial return from this foray had not been what we’d hoped, there was one significant asset we did receive. Survival in the construction industry required me to chase the details, be anal about every aspect of whatever I was involved in, and to question everything. (Linda already had the details obsession skill locked in. ) This would serve us well in our future endeavors.

For going cruising, we thought about building a 60’ version of Beowulf VI, but quickly realized we wanted something that would recover from a capsize, i.e a monohull sailboat. We talked to Bill Lee and paid him a small fee to do the preliminary design of a 12′ x 60’ monohull. Fortunately we came to understand that our prior racing experience did not mean we were qualified to make the right decisions, and we stopped in time.

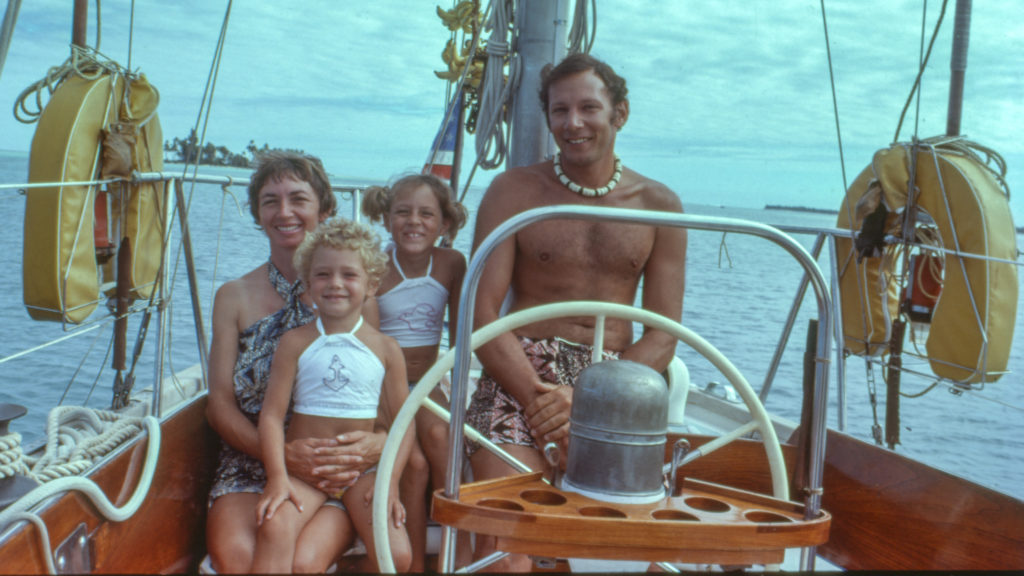

Good fortune lead us to Intermezzo, a Bill Tripp designed racer/cruiser, that had been custom built by Columbia Yachts. This was her original owner’s second C50 and it showed. She had 24 bags of sails, was loaded with electronics, and had a market value of roughly three times our budget. But her current owner had a problem, he had a margin call, needed cash within a couple of days, and was willing to accept our offer. We called two people to see what they thought about Intermezzo. First was Swede Johnson. Swede had helped design the rig for the original owner, and had sailed aboard. He confirmed she had been raced hard. Second was John Rousmaniere. Both Linda and I vividly remember looking at this enormous yacht with John from her dock behind a home on Newport’s Linda Isle, wondering how we’d ever handle such a beast (in those days 35 feet was considered the right size for us). John calmly stated the obvious–we did not have to use all that sail area. We could sail reefed down and still be quick. We arranged for a haul-out at Newport Harbor Shipyard two days hence, surveyed her ourselves, and five days after our initial viewing she was ours.

We were aware that the CCA waterline rule-influenced design was sub optimal, but we could afford her, and she got us away with minimal investment.

Our first trip to exotic Catalina was a big hit, except for a little seasickness. We quickly learned that the 160% overlapping genoa was not going to make the grade, and that we really did not need five spinnakers, three mainsails, and a host of big jibs.

Our comfort, boat speed, and safety were all constrained by the crankiness of the long overhangs and unbalanced hull lines that were part of racing rule formula. In short, it was steering control limitations which set the parameters for everything else.

Mind you we were not complaining. We were out in the South Pacific cruising, living everyone else’s dream.

Even if the engine was located beneath our feet in the salon, or the hull pitched uncomfortably upwind, had almost no ventilation, 24 through-hull penetrations any of which could have sunk us, and no lightning grounding protection, we were cruising. This boat was a leaner, the slightest puff and she’d be on her ear. She pitched badly uphill and had one speed to weather–full on. Her one virtue was light air speed, she was quick then compared to our neighbors. We partook in numerous unofficial “races” and a few real ones. With one exception, our anchor to anchor time was never beaten in any passage.

In those early days we relied on celestial navigation, which was great when you could get sights, but it was often overcast. We quickly learned that high speed reduced navigation risks from current and drift.

Two close calls with reefs taught us another lesson: a comfortable watch-standing position with good sight lines was essential in these waters. The first near miss occurred at the end of a rough passage from Bora Bora to Suvarov Island. We’d been without a celestial fix for several days, relying on advancing single lines of position from sun shots. We were within an hour of giving up on finding this difficult landfall and heading due north for a day to make 100% certain we had cleared the surrounding reefs, when a faint smudge appeared ahead along with a slight change in the color of the cloud bottoms. The pass into this low lying atoll was dead ahead. The working jib was poled out to port, the main to starboard. The pole foreguy and main boom preventer went to the bow docking cleats.

I had been on watch worrying for five hours. Relieved, I started below for a late breakfast. Then, for some reason decided to wait a bit longer. Two minutes later I was staring at the barrier reef between us and the pass. We were well south of where my running sun fixes had indicated. We jibed over, reached along the reef edge to the pass and entered the lagoon. It had been a close call.

In Tonga we rigged the foreguys and main boom preventers so they came aft to the cockpit.

The passage between Tonga and Fiji still not easy today. In those days it was downright dangerous. Midway you had to thread your way through several groups of open ocean reefs and islands. Shortly after departing Vavau an overcast had rolled in, and we’d not had a single celestial observation in the ensuing days. The full moon spread enough light through the clouds that I could see the waves breaking on Horseshoe Reef. We had been set 60 miles north of our assumed position. The combination of a watch on deck to keep an eye forward and the control lines lead aft enabled us to escape. Linda and I vowed from then on we would always have someone standing watch on deck in potentially dangerous waters.

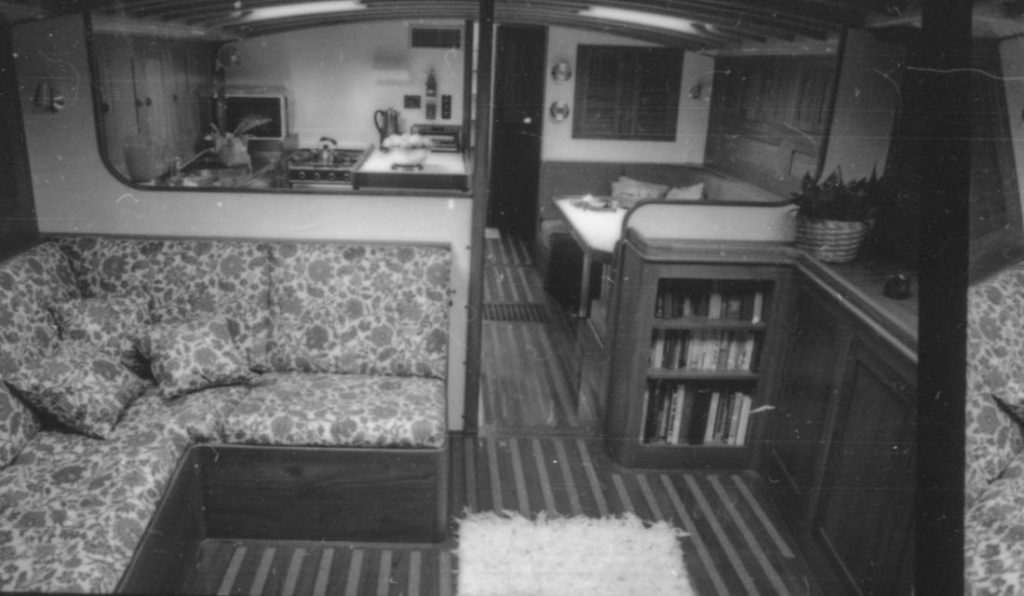

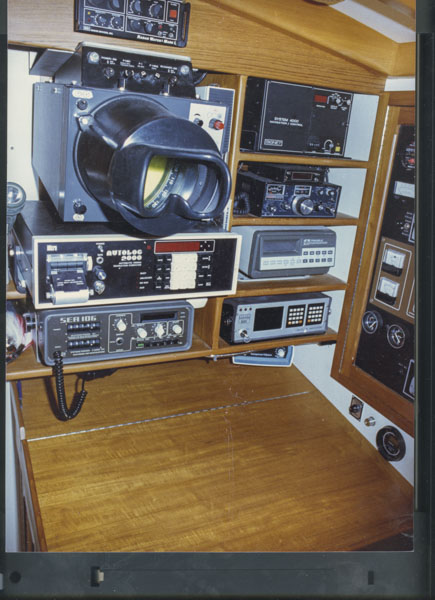

Lest you think we were living in extreme discomfort by the standards of the day, it was just the opposite. Before leaving Southern California we’d hired a local boat builder, Lou Varalay, to help us make some changes. The forward port side pilot berth was removed to create a better lounging area, and a niche forward and outboard for our radio gear.

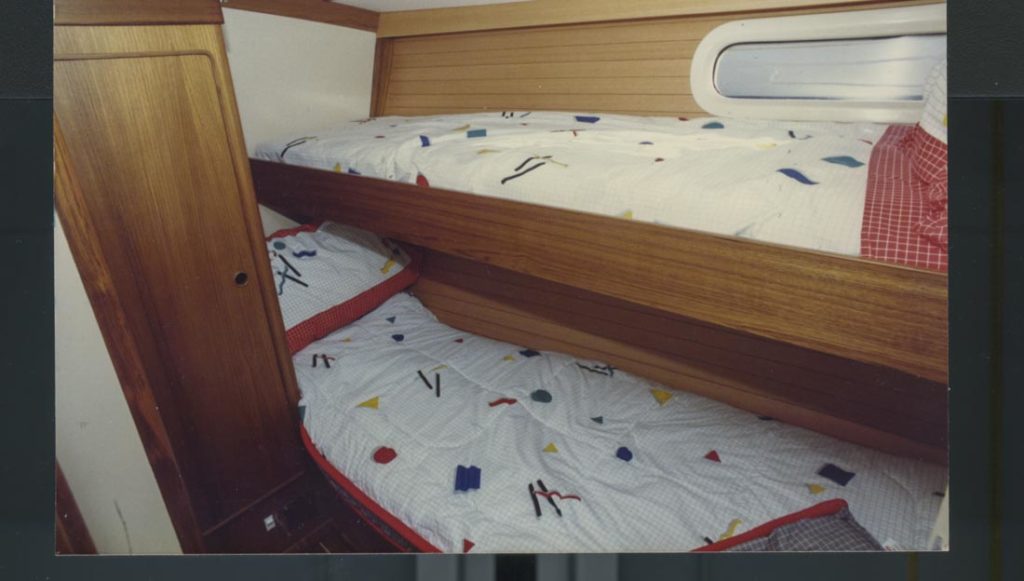

The kids slept in the starboard pilot berths.

And the parents were forward in a queen-sized bunk that had formerly had been pipe berths and sail storage.

In New Zealand we decked over the big cockpit, a vulnerability we wanted to be rid of, and created a double cabin for the kids.

Nothing else we’d seen since leaving Southern California was sufficiently alluring to get us to quit cruising long enough to get into a boat design and build cycle.

Then one afternoon in Auckland’s Westhaven marina, everything changed. Our neighbor on the adjacent end tie to the east invited us to go for a sail. Bernie Schmidt, like many Kiwis of that era, had designed and built Innismara himself. She was 60′ long overall, gave away little to overhangs, had a ten foot beam and little freeboard. In some ways she reminded us of Beowulf VI. Innismara looked huge compared to our diminutive Intermezzo, but as we charged down the harbor at ten knots, with just the main and boomed staysail, it was apparent that she would not be that hard to handle. Innismara’s balanced lines, the result of her long skinny hull, made her a delight to sail with virtually no weather helm, even though we had the full main up.

We started kicking ideas back and forth. What if we got rid of the trunk cabin and made her flush deck, and then added just a touch of beam? We would have a large interior, we’d be fast, and the kids would each have their own stateroom. Rather than fill up the hull with stuff we could leave the forward quarter open and stow sails and ground tackle there. We could leave the aft quarter empty (the aft engine room idea had not yet come into being), and keep the interior to just the center where it was easy to build and motion was minimized.

Our friends from the cruising fleet, Jim and Cheryl Schmidt, were enthusiastic as they joined in on our dream sessions. My dad became enamored too, and before long we were hard at work on the first of the Deerfoot Series–not that we ever thought there would be more than three boats.

Now a psychological digression. We cruised uninsured–almost everybody did in those days. Intermezzo represented our house capital. There had been 24 through hull fittings. She had no watertight bulkheads, huge cockpit locker hatches opening to the interior, and no lightning bonding system. In those days, one out of ten yachts crossing the South Pacific ended up on a reef. We had several very close calls. On the other hand, Jim and Cheryl were cruising on a steel plated yacht with five watertight bulkheads. You can see where this is going. The combination of these experiences formed our design and construction philosophy.

The 68′ Deerfoot was the first afloat. She was 14′ wide, drew eight feet, and had a somewhat larger trunk cabin than Innismara. A mistake in the early design calculations by Doug Petersen, who drew the lines, had Deerfoot with her longitudinal center of gravity too far forward for the hull already constructed.

Although we did not recognize it at first, the solution turned out to be moving the engine all the way aft from the traditional position under the salon floor. The benefits of this approach were so great that almost all of our yachts have been done this way since.

Jim and Cheryl’s Wakaroa was next. With her flush deck configuration she was closer to our ideal, offered more usable interior volume, and a somewhat higher, dryer deck, that had benefits in terms of the inverted stability curve.

Wakaroa would average an easy 9.5-10 knots when reaching and would do even better with the kites up.

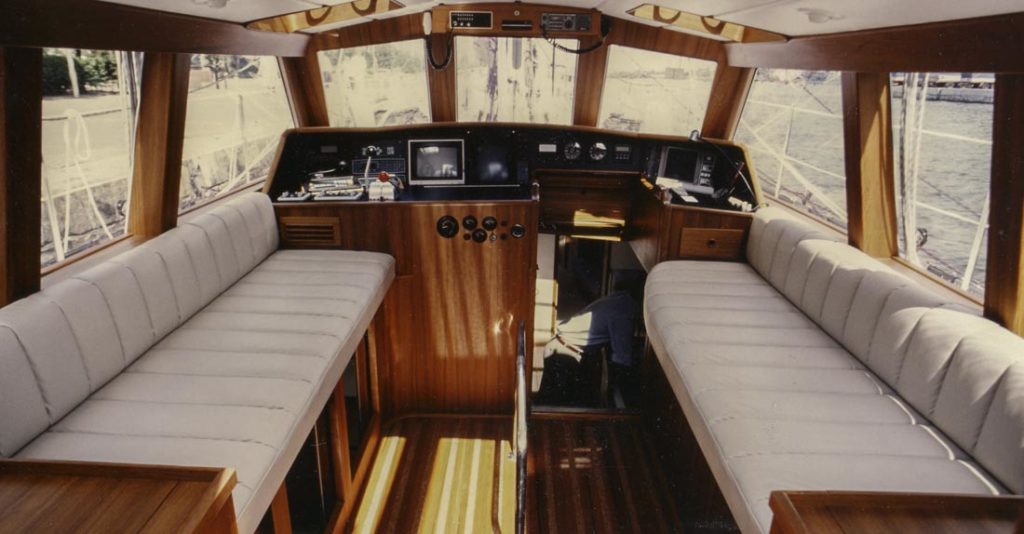

These photos don’t begin to do the interior justice.

At sea, if necessary, you could live between galley and adjacent dinette, and nav station…

…with its highly functional layout…

and a pair of aft cabins, with your body constrained from falling. After that, a couple of steps and you were in the cockpit.

Back in time to New Zealand, and we and the Schmidts tarried a bit that fall before departing for New Caledonia. The beautiful Indian summer held us captive. The warmth and quiet, not to mention the delicious steamer clams nearby, made us linger a couple of extra days. When we both left Whangaroa harbor it was into a light breeze and calm sea. The Schmidts powered over the horizon in their 70′ WinSon while we waited for the breeze. The next day, the center of high pressure that had given us such a glorious few days had been replaced by the back side of the high with a cold front compressing in. It was blowing hard, on the nose, and we had one of the worst passages imaginable. Everything was wet.

Formalities having been completed with the Gendarmes in Noumea, and after consuming the requisite fresh baguettes, cheese, and of course ice cream, we set about to dry the boat out, rinse bedding, and try and remove salt water from bunk cushions.

Med moored alongside was a flush deck 50′ steel cutter, with a final leg across the Tasman left to complete their circumnavigation. Commenting on our laundry hanging around on deck I made an innocuous statement to the extent that all boats leak at sea. “Not if they are metal and you don’t drill holes in them,” came the response.

We don’t seem to have any Noumea photos around but the shot above is Sarah working while we were anchored near Havana Pass.

Havana Pass took us to the Loyalty Islands just north of New Caledonia.

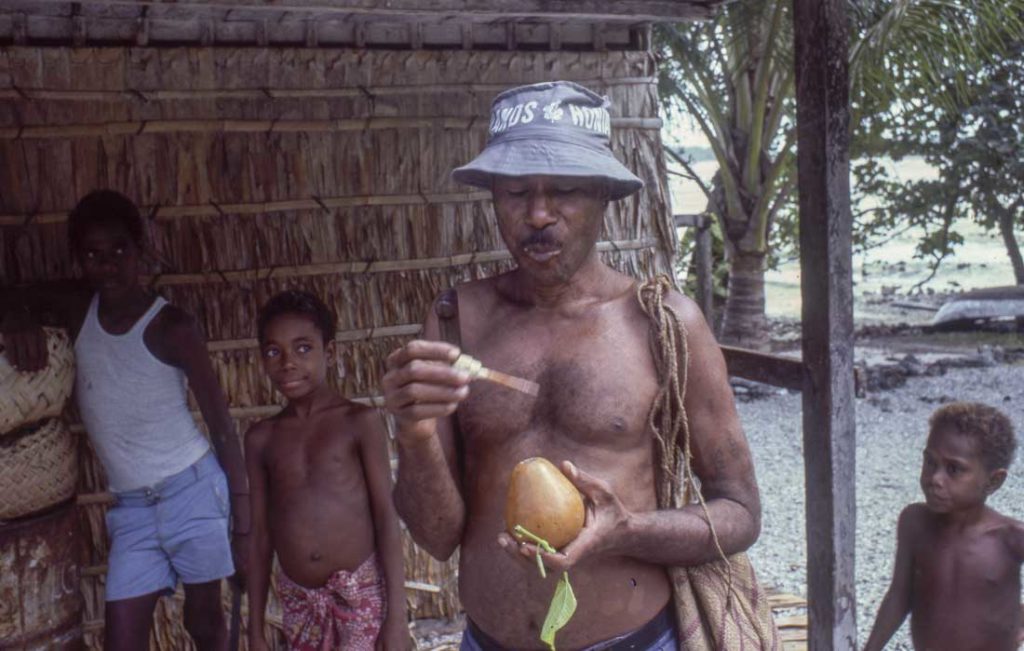

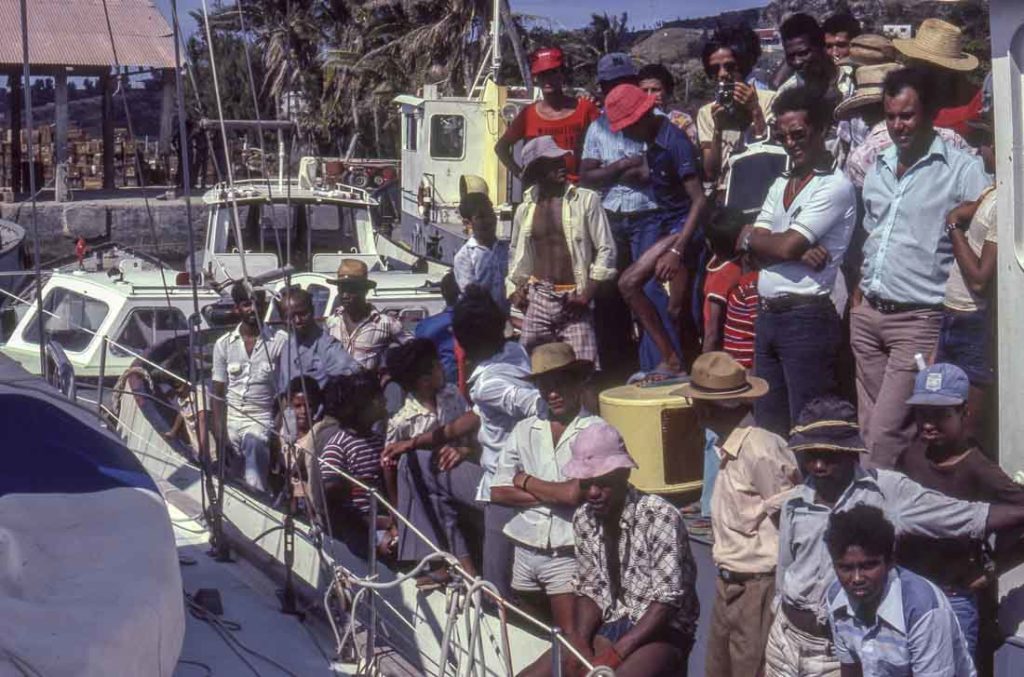

And then on to the New Hebrides…

…Solomon Islands, and New Guinea.

In those days this was a fascinating area, still amazingly remote, and the locals were as curious about us as we were about them.

While on passage to Santo in what is now called Vanuatu, we were sailing downwind in broad daylight, keeping watch forward, reading a new book by Henry Kissinger, when the water color suddenly changed from blue to green to white in less than a minute. By the time we had grabbed control of the steering from the wind vane, we were amongst the stag coral. Intermezzo still had momentum, and we turned onto a close reach so that she would reduce her draft by heeling over. Linda came racing up on deck, took the helm, and I climbed to the lower spreaders to try to find a way clear. There was simply no path out that did not involve breaking through coral. We maintained sufficient speed to force our way through. Finally free, we stopped for a moment to catch our breath, check the boat, and detour around this area of shallow water.

When we finally reached Santo, we learned that the ocean floor had lifted in this area a few years earlier, the result of a major earthquake. Aside from our shaken psyche, Intermezzo was basically okay.

During our stay in Melanesia, the ferro-cement ketch Heart of Edna made a mistake in the Louisiade Island group off eastern New Guinea and found herself permanently stuck on a barrier reef. Friends on the steel Australian ketch Makaretu headed off to help with the salvage operation. Sadly, the hull was a total write-off but they were able to remove the rig, hardware, and engine, and along with John and Jan Nichols brought the lot back to Australia.

We were getting periodic updates via ham radio from Makaretu and when it was all over I asked our friend Brian what lessons he’d taken from the situation. “Have a metal boat,” was his reply.

From New Guinea you traverse the Torres Straights to Australia’s Darwin, with its 20’+ tides. Big tides make using grids for maintenance a possibility, which offers all sorts of advantages to serious cruisers. So “gridability” was added to the desired hull characteristics list.

A month-long stop in Bali, Indonesia, and we were ready for the ocean once again.

Crossing the Indian Ocean, particularly in the southern trade winds, is not for the faint of heart. The trades are typically boisterous–30 to 35 knots from the SE with a crossing SW swell.

The hops are long, Christmas Island is the first stop with an open roadstead. Next comes the atoll Cocos Keeling.

The anchorage in the lee of Direction Island is a welcome respite, if surprisingly crowded.

The social scene on the beach is busy. It is not easy to leave an anchorage like this when you know it is going to be rough on the next leg, but the hurricane season in the western region of the Indian Ocean is not to be trifled with, so we were forced to move on quickly.

On long passages Linda maintained the school routine, allowing the kids to have more free time when we were at anchor.

School was in session in spite of the sea state.

It was a good thing too as Rodrigues, the next stop, was a fascinating little island, with caves to explore, and interesting folks ashore with whom to mingle.

The harbor was tiny. The entrance pass, blasted out of solid reef limestone, was not much wider than our 12-foot beam.

At sea again after a short stay, school was back in session. And our tradition of reading stories aloud continued.

Long term cruising revolves around a floating, ever changing social scene. Seasonal weather patterns herd you into groups that tend to migrate together. You might go different ways for half the year, but eventually boats in your group tend to end up in certain locations. Mauritius is one of those. When children enter the equation the groupings tend to be even tighter. This eight-foot dinghy is carrying a cargo of Elyse and Sarah, Tara and Eric Naranjo, Veronica Hast, and young Vinaka with his dad John Wishnovick at the helm.

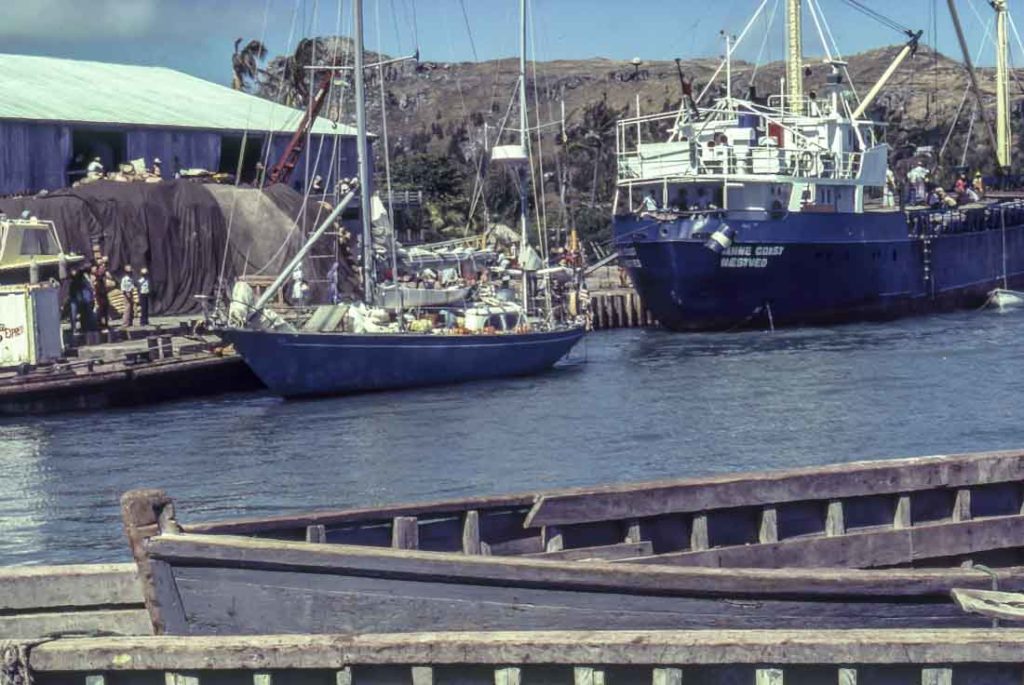

In Mauritius we met Yves Betuel, a local sailor who ran the Taylor Smith Shipyard. We needed to do some welding on our spreader brackets, and as Yves took us across the boat yard to his welding shop I noticed they were constructing a tug and some barges. That immediately got us thinking and we asked Yves if they might be interested in quoting on a steel version of our dream boat. The idea was to get the basic hull finished, rig it, and sail back to New Zealand for the interior.

Yves gave us an attractive quotation and then told us that as the steel had to come from South Africa we would get a better overall price there.

The 1,500 nautical mile passage between Mauritius and Durban, South Africa is one of the roughest in any circumnavigation. You are heading west into a collission with the prevailing weather systems that move east, there are the shoals that influence the sea state as much as 200 miles south of Madagascar, and then the infamous Agulhas current waiting at the end. Our trip was typical, with four gales and then a final black southwester into the current with continuously breaking seas. One yacht in our neighborhood was rolled over, and a second was severely knocked down. We had no problems other than our usual leaks.

In Durban, we became friends with a local accountant and asked him for advice about doing business in South Africa. When he heard our goals he suggested we apply to the Reserve bank for what was then known as Financial Rand, a discounted currency, used as an incentive for those starting export-oriented businesses.

Our application was approved and eventually we found a builder in Cape Town to do the metalwork. We also met a talented naval architect, Angelo Lavaranos, who did the basic design work for us on what became Intermezzo II.

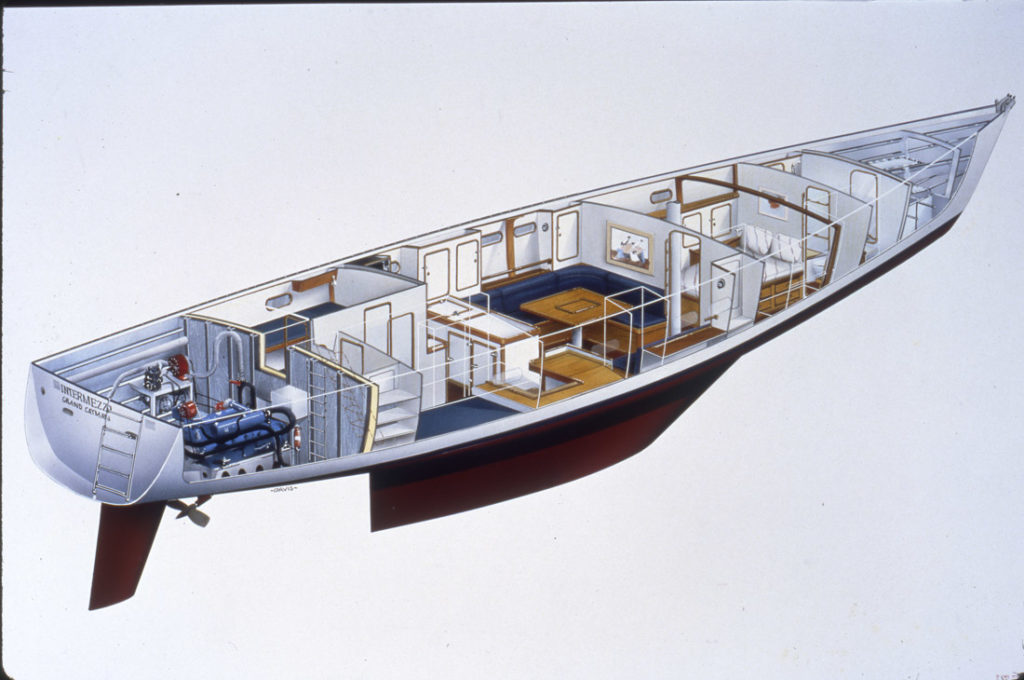

The three dimensional rendering of Intermezzo II above first appeared in Sail Magazine. It was created by the late Steve Davis, a good friend, talented artist, and over the years an important sounding board for our ideas. Steve helped us to develop our ideas, and he also did the artwork for almost all of our books.

Our concept of the perfect cruising yacht had evolved further. Nirvana now lay in metal, with aluminum preferred over steel. Shallow draft, no more than 5.5′ was next. This was not only to expand our potential cruising area, but to reduce the risk of unexpected groundings. Aft engine room, separate forepeak, with isolating watertight bulkheads were all non-negotiable.

Discussing the hull lines with Angelo we both wanted to do away with overhangs. However, re-sale considerations at that point dictated that we have at least short overhangs. Even so, the hull shape was considered radical when launched.

In order for us to pay for a new boat we needed to sell Intermezzo. We had just enough set aside to get the metal work started, and although we had other assets, these were in the form of real estate and we did not want to touch those investments. We advised the hull builders that they might have to stop work if we were delayed in finding a buyer. We were within a week of making that call when a new owner for Intermezzo came along.

It’s funny how some people keep cropping up at important points in our lives. Once again here was John Rousmaniere. John had asked us to write our very first article in 1975 for Yachting. He’d encouraged us to continue writing while cruising. While we were living in Fort Lauderdale waiting for Intermezzo to sell John had introduced us to Eric Swensen at W.W. Norton, John’s own publisher. This resulted in us writing our first book, Circumnavigators’ Handbook.

When we had begun our cruising life, although I had grown up afloat, and by the time we bought Intermezzo we were both competent sailors, as mentioned earlier we did not have a clue about the real world of long distance cruising. The same would be said for 99% of the “experts” with whom we’d had dialogue. The learning curve was steep. Just a few examples: our boot stripe was too low, we did not have a single fan aboard and it took multiple hours a day on our little diesel engine to keep the tiny fridge and freezer cool. But by the time we’d arrived in Fort Lauderdale we did know something on this subject. Circumnavigators’ Handbook was our attempt at passing what we had learned to others at the beginning of their own learning curve. The book was a success in the marine context. We received a small advance, which covered the cost of the second typewriter we needed to purchase, along with a stack of photography expenses. When the Dolphin Book of the Month Club subsidiary picked our book up as a monthly selection we received a few hundred dollars more.

In those days our cost of life afloat was modest. Living on a yacht sounds expensive but if you mainly anchor out, stay ahead of maintenance issues, and do most of your own work aboard this is a very frugal lifestyle. Our real estate investments were not yet cash flowing, so working as freelancers, writing about sailing, provided us with most of our cruising kitty.

We worked with several talented editors at various sailing magazines. The one who taught us the most was Patience Wales at Sail. A story Linda had written for Patience about cruising with children turned a light on for us. When the story appeared in print, it was somehow different, stronger, more descriptive. We could not figure out what had been done. Patience kindly allowed us to see her edit. We were surprised by what we found, to say the least.

By moving just a few words around, changing tenses, and making a few minor edits she’d made a huge difference. Showing us how’d she done it was a wonderful writing lesson for us.

Returning now to Cape Town, we made arrangements with a local boat yard to rent their facility and hire their crew directly. This allowed us complete control. These local workers had good work habits and a reasonable degree of skill, and in the end this project turned out to be the most efficient we’ve ever done.

The social and political situation in South Africa was rapidly changing while we were there, and we were able to have our traditional launching party for the boat builders and their families at the Royal Cape Yacht Club, a first for everyone in the area.

Both Deerfoot and Intermezzo II were fitted out with short swim steps.

The primary purpose of these was to make it possible to climb back on to the boat if somebody fell overboard, otherwise impossible due to high freeboard. Once we began to use swim steps it quickly became apparent that they had many other benefits and their size began to increase.

The halyards and reefing lines were led to the cockpit, and the mainsail trim angle, until the true wind was almost abeam, was controlled with a full width traveler. We had a single primary winch aft of the helm, and two secondaries at the end of the cockpit coamings reachable from the wheel. The mainsail had a full length upper batten, and we had hank-on headsails.

Intermezzo II was the first of our boats to have hull windows.

The mast was well forward for a cutter rig and the boom purposely did not overhang the cockpit. This allowed us to have a lower boom which had numerous advantages: easier to attach the halyard, remove the sail cover, furl the sail, a lower center of gravity and more sail area with a lower center of effort. The negative is that if you are in the way of a jibe you are going to get punched in the gut. But would you rather be hit in the head with a higher boom?

Four large deck hatches gave us lots of light and ventilation in the great room.

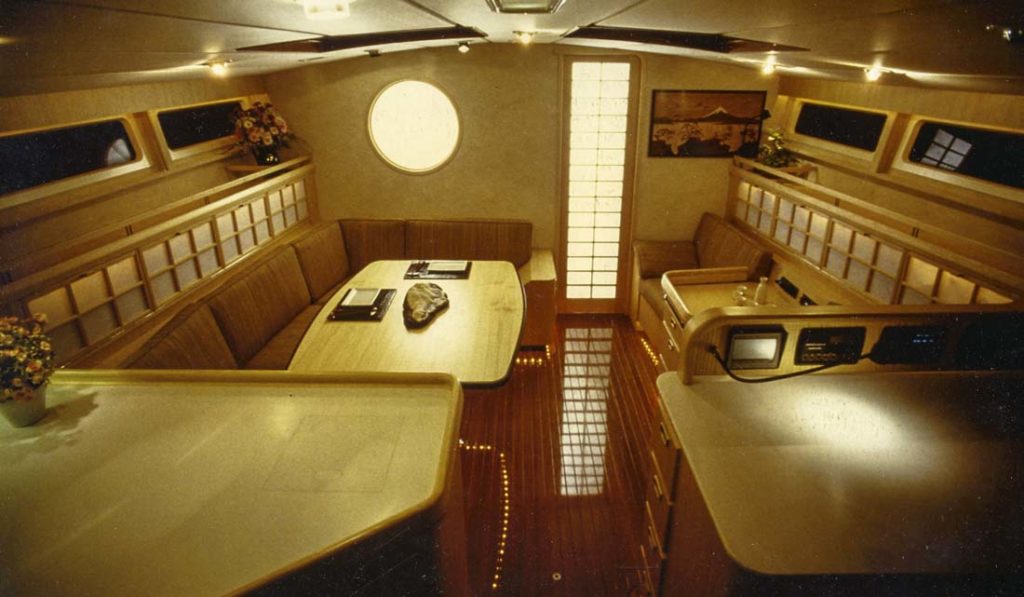

The flush deck layout gave us 13′ of interior beam and 14′ of length into which we could fit galley, office, and salon, the great room. Wakaroa used the same great room approach. It worked so well that it became the standard for most of our projects.

We decided to fit twin headstays so we could fly two jibs at one time. What we failed to understand until it was too late is that twin stays split the headstay tension, so each has significantly more sag then if a single headstay was used. We never did this again.

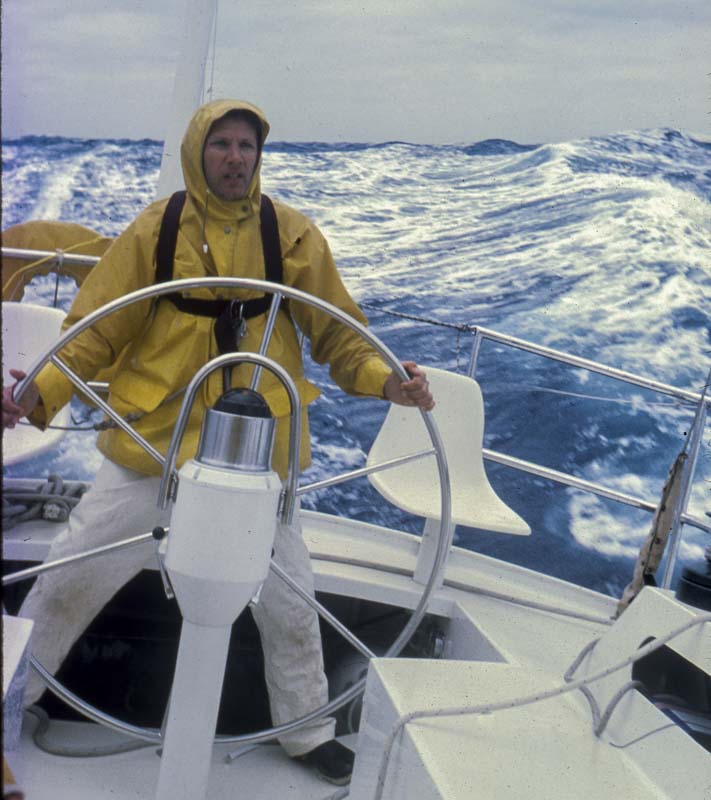

Our shakedown cruise was a 6,000 nautical mile 30-day passage to Antigua in the West Indies (with a short stop at St. Helena). We had done the same trip the previous year in little Intermezzo with no stops in 37 days. This passage had been normal for us in that it was unpleasant, or at least wasn’t great fun, it was just something that had to be done to get where we’re going. In contrast, the second passage was extremely comfortable in similar conditions.

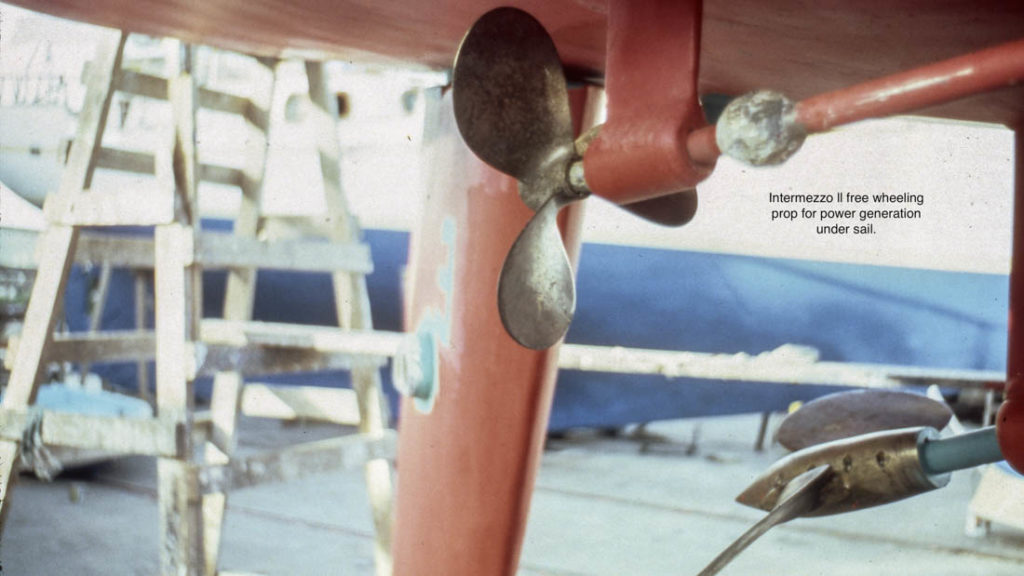

The free-wheeling charging prop was a technical success. Coupled with a low rpm-optimized alternator, under sail it generated more power than we could use.

Intermezzo II performed beautifully, she was easily steered, tracked well, and when the autopilot failed with 1,000 miles to go little Sarah could take a turn at the helm and keep her on course without difficulty. Overall she was much easier to sail than had been the case with our previous boat.

We decided to take a year and see if we could make a business out of this. At the Annapolis boat show there were long lines waiting to see the boat, and we were the focus of feature stories in all the major magazines. But our radical-looking flush deck configuration, coupled with no exterior teak and a very light and open interior, was a bit too much for the marketplace at the time.

After the show Linda flew back to Fort Lauderdale, where Elyse and Sarah were being looked after by my Mom, who had come in to allow us some time to work the show. Some old friends from our days in the Malibu Yacht Club had come by at the show and offered to crew. Sean and Lorraine Holland were about to get the ride of their lives. Shortly after departure from Norfolk at the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay, our favorable northeast breeze turned into a true nor’easter, literally a survival storm which took two yachts to their graves. You can read about this in detail in Surviving the Storm, or by clicking here.

Sean snapped the above photo after we’d rounded Cape Hatteras and things had calmed down.

What saved us was the fact that, once heeled past 35 degrees, the keel and rudder would begin to lose their grip and Intermezzo II would slip to leeward. The more she heeled the faster she slipped. When we got knocked down by a breaking sea it was this slip factor that allowed us to dissipate the wave energy before we flattened or worse. The effect is similar to what happens when you raise the centerboard of a dinghy in boisterous weather, or lift the leeward board in a catamaran. Wherever possible thereafter skid factor became a bottom-line criteria.

During this period, a sistership was built in Cape Town, and although we were ecstatic with Intermezzo II, 62-2 had six pages of fine-tuning notes incorporated in her build. Which brings us to an observational process comment. If you are a multi-project type personality, already thinking about the next while the current is not yet fulfilled, the time to make your notes about what you would change in the future is at the beginning of your relationship at sea with the new boat. Details you don’t like, mistakes, fine-tuning, issues which are now apparent but were hidden earlier, should all be noted. As you grow accustomed to your new ride, many of these next-boat refinements will fade from consciousness and be lost.

Over the years several experiences have lead us to Eureka moments. One of these occurred on the last leg of our circumnavigation when we stopped in Cabo San Lucas to break up the trip and top off the fuel tanks. Diesel was 13 cents per gallon. The combination of a quiet, reliable engine and an aft engine room made powering much more pleasant than what we were used to. Add in the cheap fuel and it was apparent that the trip ahead of us would be more comfortable, faster, and much less costly burning diesel than exposing rig and sails to the upwind passage.

This visit to Cabo coincided with the aftermath of a weather system that had pushed numerous yachts onto the shore of the exposed anchorage.

While several mistakes were made that lead to this mass calamity, it underscored that bad things will occur, and folks do commit operator error (ourselves included). This reinforced our ideas about building in extra factors of safety for inevitable screw-ups. As the years have passed, we have grown even more conservative in concert with how much we’ve seen and experienced.

On the way up the coast the two of us discussed what we’d seen at Cabo. We just could not get the image of those stranded yachts out of our minds. By the time we’d reached the US/Mexico border we had a new book outlined. This would become Bluewater Handbook.

We completed our circumnavigation, crossing our outward bound track off Southern California, and stopped in San Diego to clear Customs. The plan was to sell the boat, buy a house, and get into the business of turning around sick companies.

It was during this timeframe that the single-handed around-the-world race changed to a 60-foot length overall rule and did away with handicaps. Suddenly, there were lots of yachts in the magazines that looked somewhat like us, and the telephone started to ring.

The day after clearing in, a former heavy weather crew from the Beowulf V days called about his dream boat. We had nothing yet lined up so agreed to do a big surfboard. The owner’s comment was that he did not care about cruising the boat to weather – the crew would do that – he just wanted to surf, fast.

There is a trade-off in design characteristics required for upwind as opposed to downwind sailing. Upwind you want a narrow entry to get through the waves. Downwind the optimum is flatter, more easily steered. Locura was really flat, and could be helmed with two fingers at speed with two big kites set. But you paid a comfort penalty uphill.

Her interior layout was similar to Wakaroa and Intermezzo II. At last count Locura had made two circumnavigations with over 62,000 nm in her wake, so the concept must have had some merit. This was the only time we’ve sold a design package. Aside from a few early consulting jobs we realized that we prefer to control the end product.

For the past year we had been writing a monthly column for Motor Boating & Sailing, which was owned by the Hearst Publishing Group. Hearst has a marine book division and we discussed our outline for the new book. This time around we were going to try self-publishing, and eventually Hearst agreed to represent us to the bookstore trade.

John Rousmaniere stepped in once again and introduced us to Spencer Smith and Nancy Donaldson, who ran the Dolphin Book Club. They liked what we’d put together and made it their monthly selection. We knew nothing of printing and binding, and asked Spencer if he had some suggestions. Normally Dolphin Book Club paid a small fee to the publisher and then piggybacked the publisher’s run. In this case they did the first run, showing us how it was done, and we piggybacked them.

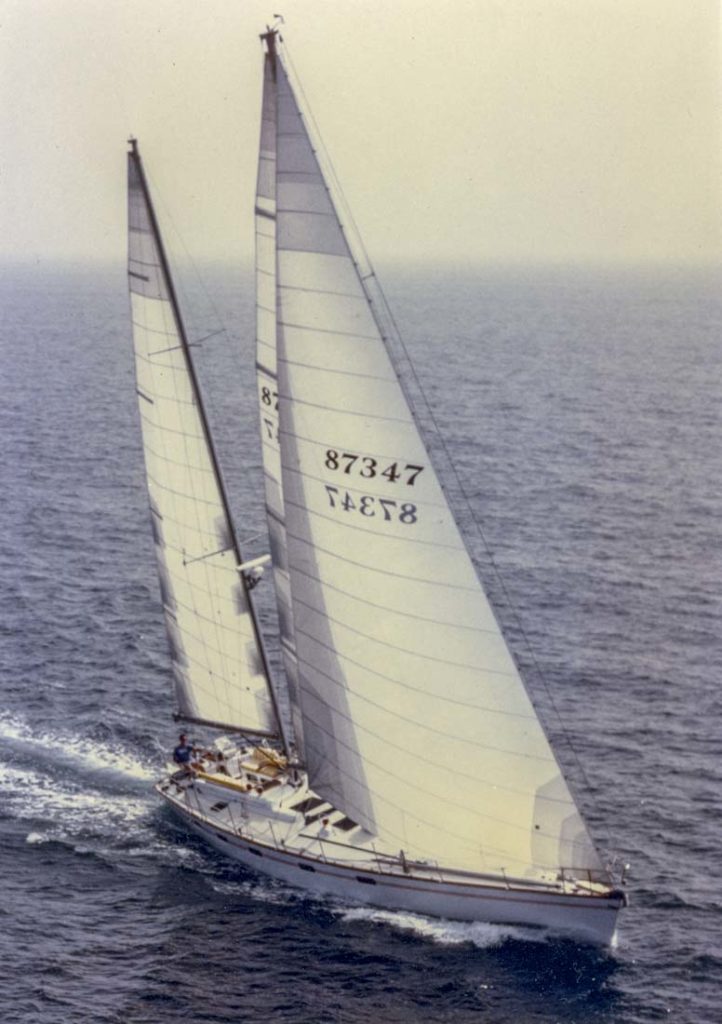

The Deerfoot 2-62s were our first series build, four of which were built in Finland by Scandi Yachts. Moonshadow, the 2-62-1, is shown above during the initial ARC race 35 years ago (in which she was first to finish).

After almost 15,000 miles with Intermezzo II, the 2-62 represented what we thought was our next perfect yacht. Her lines had a shorter overhang and were a touch flatter forward and aft, while the volume in the ends was increased compared to the first 62s. We thought we could get better surfing and upwind performance this way, steer more easily, and not pay a comfort penalty. Part of this hull shape evolution was a narrower forward entry angle that was also a touch deeper. The negative was a little extra wetted surface.

The deck layout was totally different and featured a large center cockpit for watch standing…

…with the sailing cockpit aft. This forced the crew to traverse the bridge deck going aft, which we did not like, but provided the basis for a different interior layout and the revised hull shape.

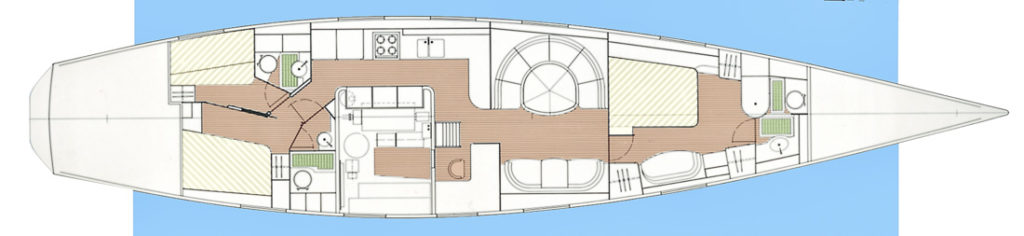

The engine room was under the center cockpit with a long galley adjacent.

There are points in favor and against this approach. One of the biggest benefits was a long galley with excellent storage, and furniture that constrains your body at sea. But the key for us was in the aft end. Eliminating direct access to the aft cockpit got rid of a two-foot wide hallway between the aft cabins. This beam could be used to add volume to the cabins or reduce hull width. The latter made for a more balanced hull shape and better steering.

With the Cabo incident fresh in our minds, the hull laminate was specified with an extra 1/2″ thickness of 24-ounce woven roving to protect the turn of the bilge from puncture, the grinding zone when aground. The keel support structure was heavily reinforced, there were added laminates in the bow for collisions, and of course forward and aft watertight bulkheads.

Moonshadow tested these features twice (that we know of). The first time was by t-boning a reef in the Tuamotus, spending a week ashore before being towed off. The second was by intimate contact with a coral head (which dented the keel).

Moonshadow has seen over 100,000 nm flow beneath her hull over the years.

To get to Nykarleby, Finland we had to pass through Copenhagen, Denmark. During this period Ulf Rogeberg was working for us, doing both design work and acting as interface with Scandi Yachts between our visits. Ulf introduced us to Paul and Sven Øeland, who had a shop doing nice metalwork. Then we met the Walsted family in Svenborg. This was during the Reagan strong dollar era, and seemed like a winning combination.

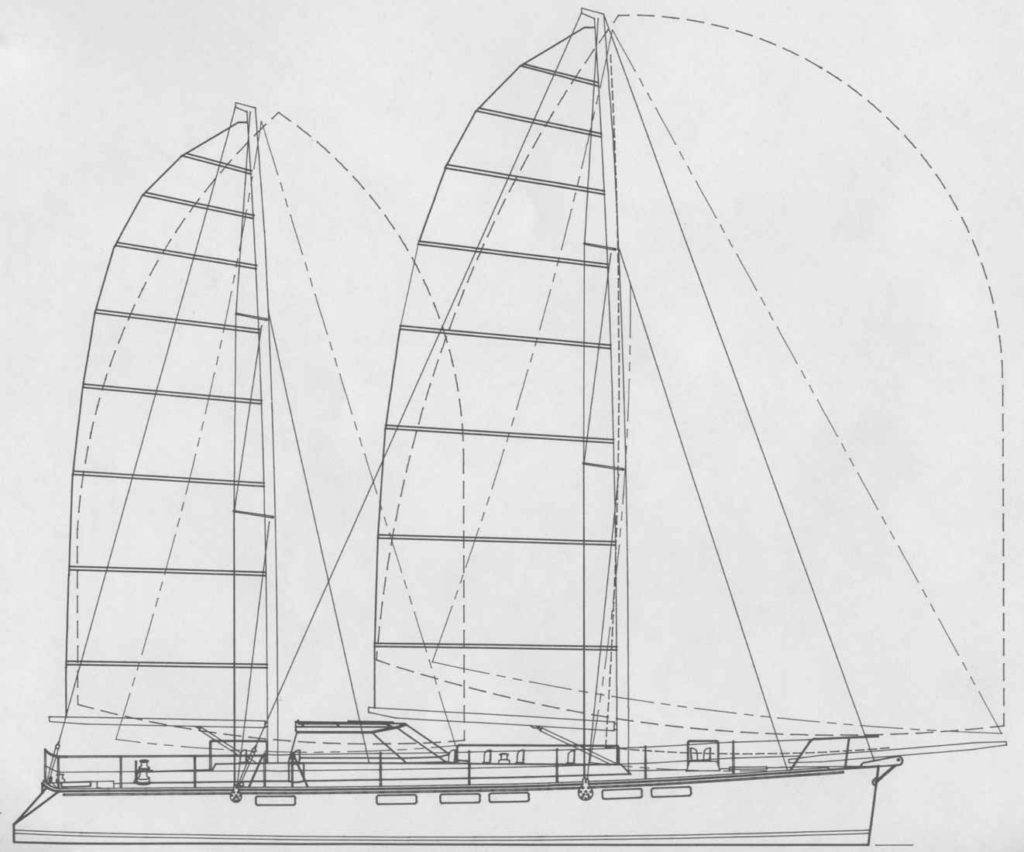

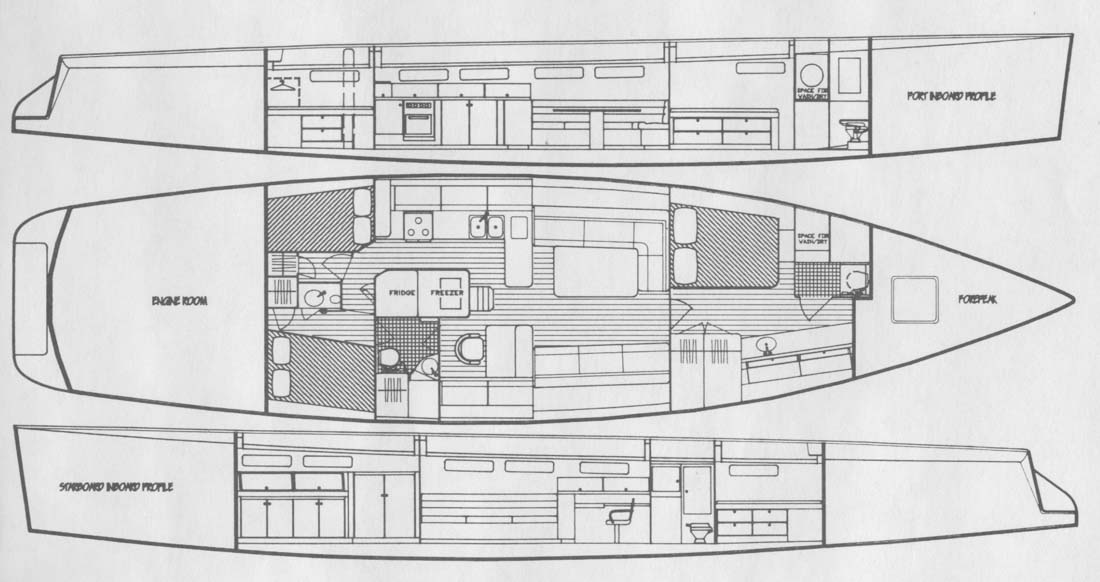

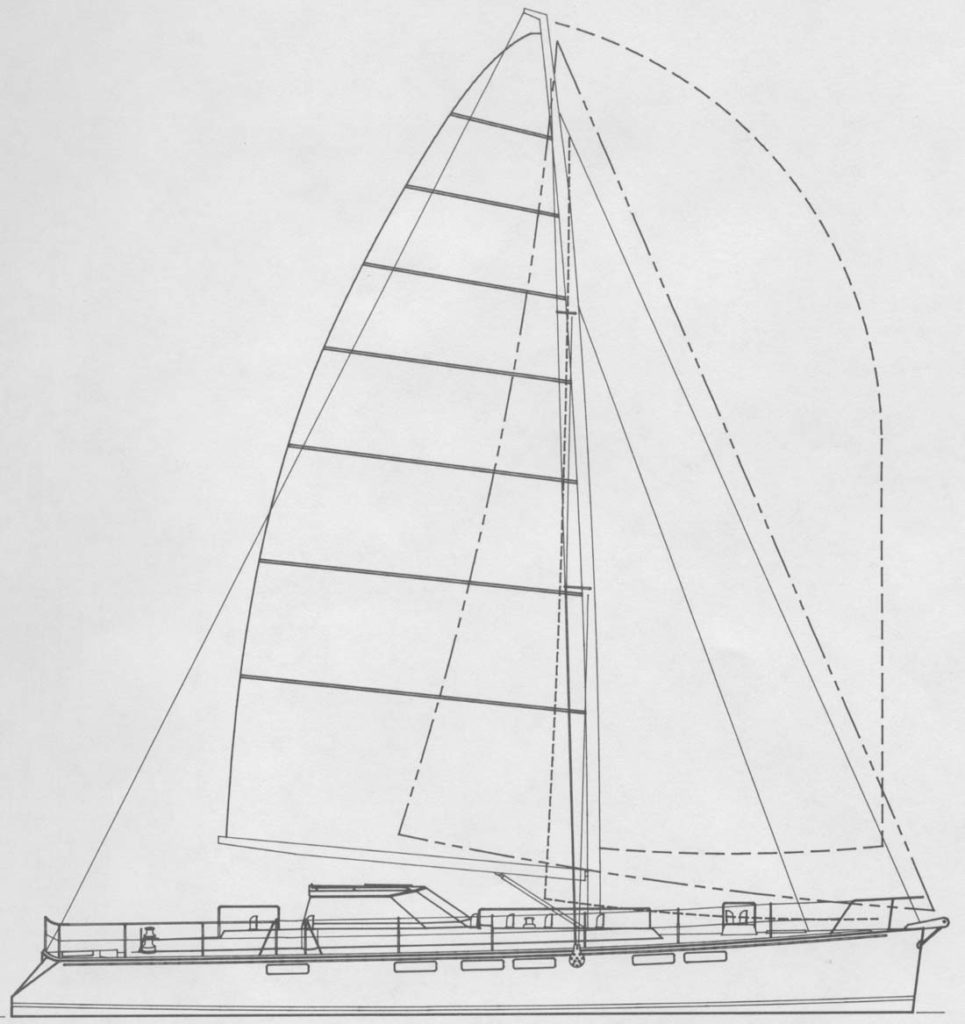

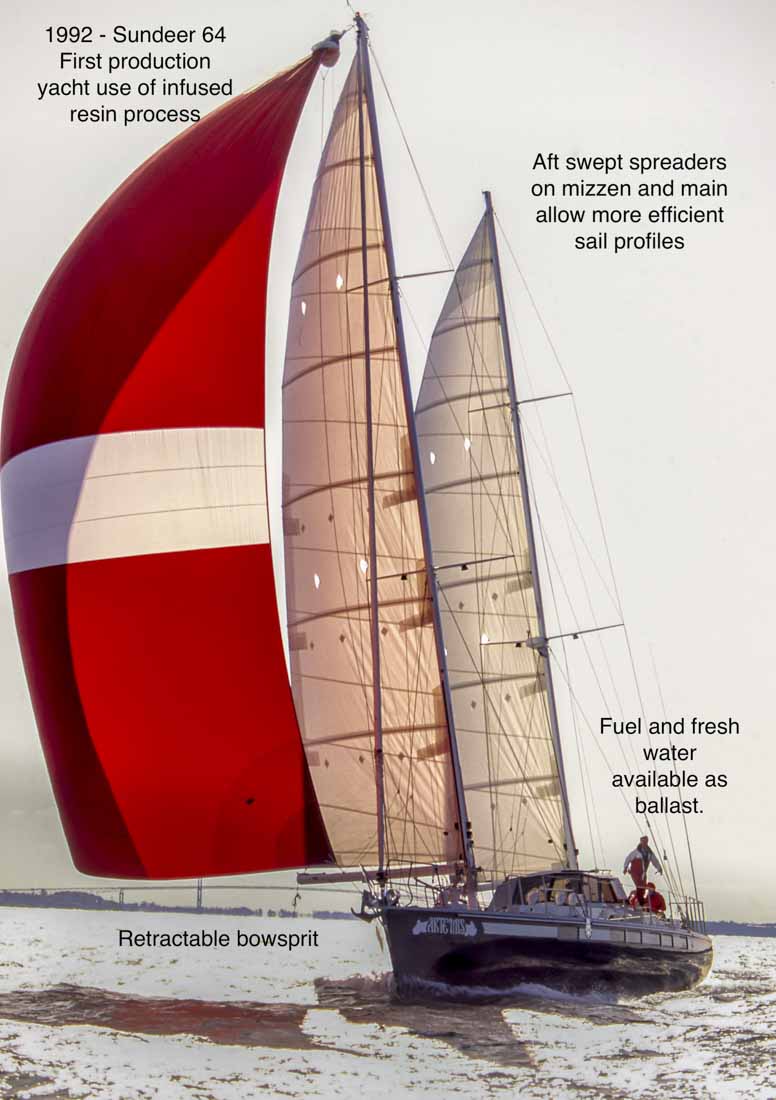

Which lead to a series of three 72′ (+) motorsailors.

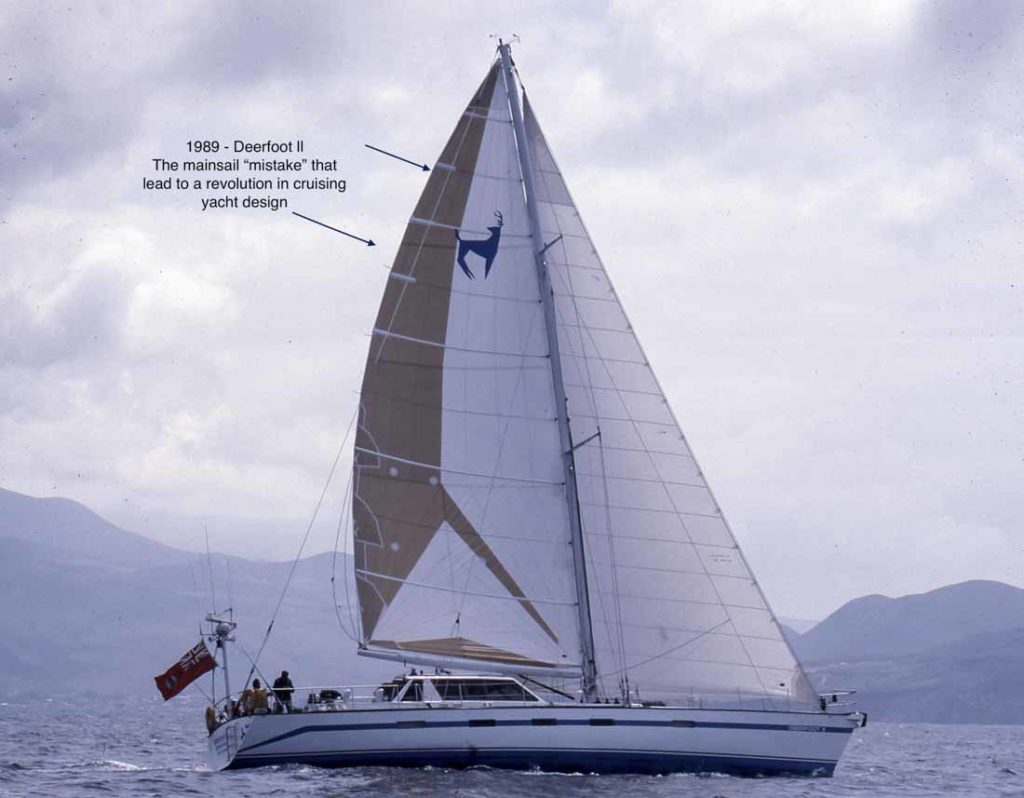

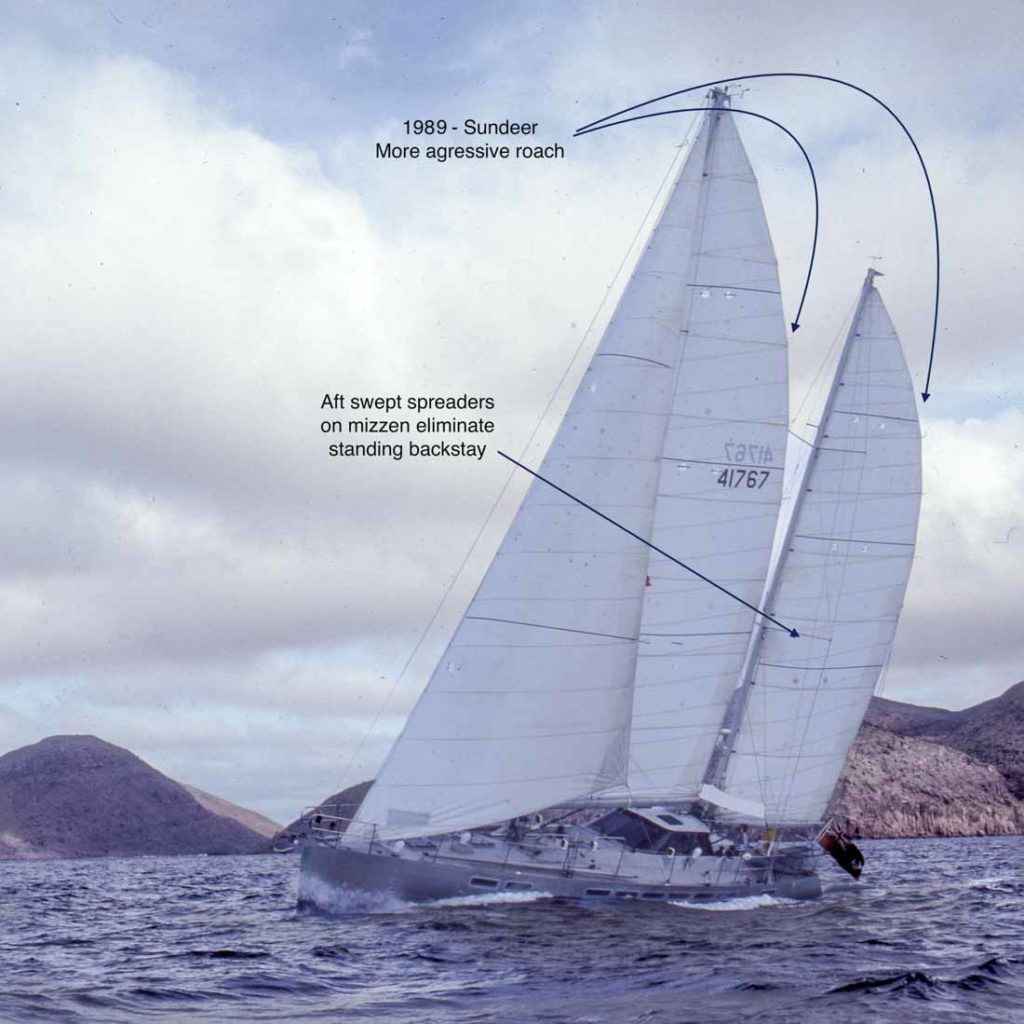

Motorsailors typically don’t power or sail very well. But we thought we had the answer to this. Use a long, modest beam (okay skinny) hull shape, and fit an oversized feathering Maxi prop. Deerfoot II and Interlude were 14.5′ wide while Maya had another foot of beam.

The swim step was extended.

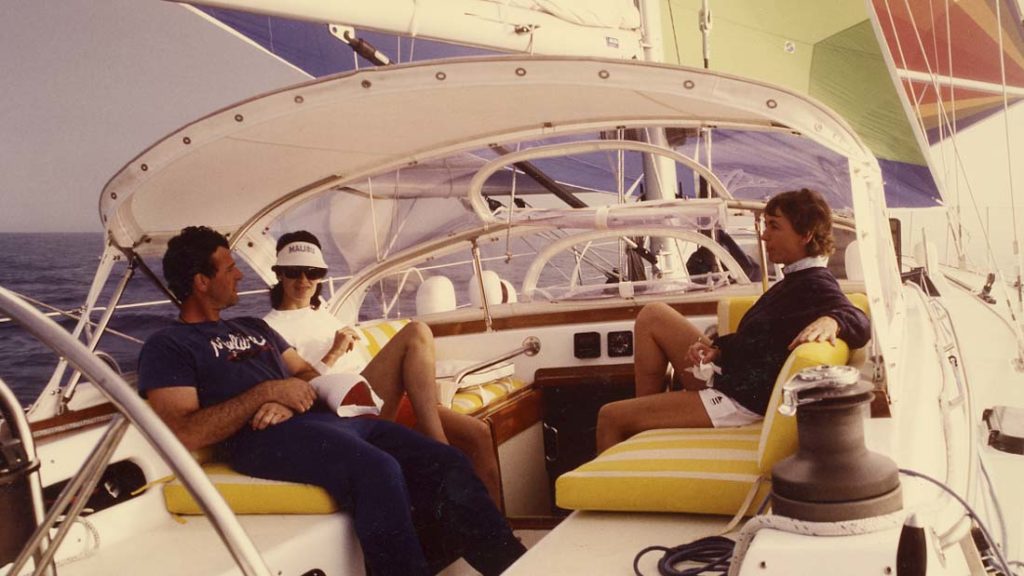

And the aft cockpit (Sarah above, driving Deerfoot II) and the midships galley arrangement of the 2-62s was maintained.

Now a word on beam. There are many forces driving yacht design, among the strongest of which is the desire for interior space. In this regard, more important to the actual beam of the vessel is what is left over – physically and visually – after structure and interior cabinets are deducted from the gross hull volume.

This Deerfoot Series of “MotorSailors” will give you an idea of what is possible. The next photos are of a 30-year-old yacht.

“Chairs” like these look nice, and work well for entertaining. But when combined with the cool-looking circular settee and table opposite, leaves nowhere to sleep in the main salon.

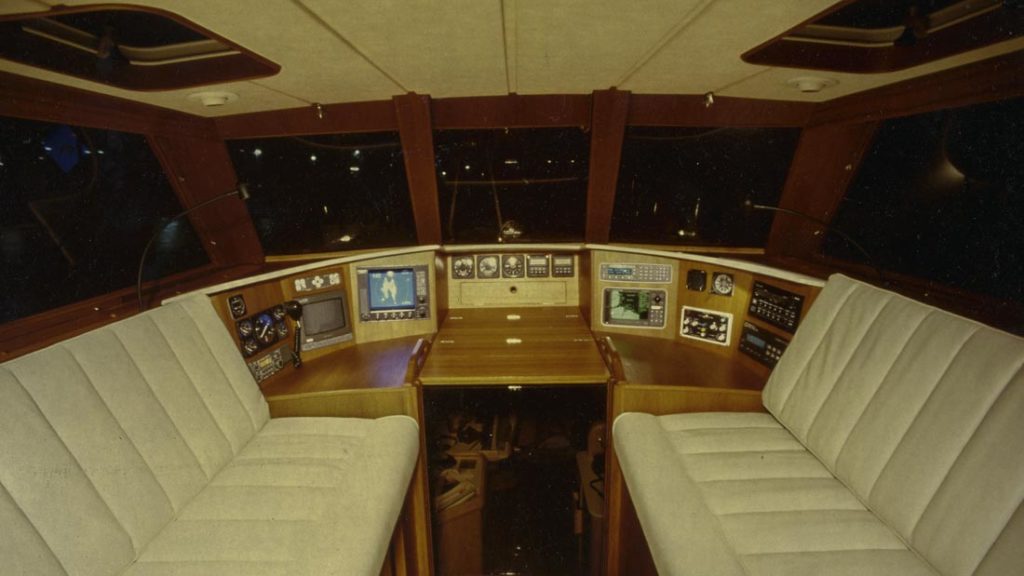

Another driver of this design was the desire for an enclosed pilot house.

Maya’s, above.

And Interlude.

A small but important detail are these dropdown panels into the galley.

A night shot of Maya’s salon. The round item in the bulkhead is an etched crystal edge lit object d’art. The door panels are high tech soji screens.

Our typical galleys were always narrow to hold you in place at sea. The preferred hip width was 24″/600mm. When there is a conflict between what works best at sea and in port, sea-going always wins.

Our typical galleys were always narrow to hold you in place at sea. The preferred hip width was 24″/600mm. When there is a conflict between what works best at sea and in port, sea-going always wins.

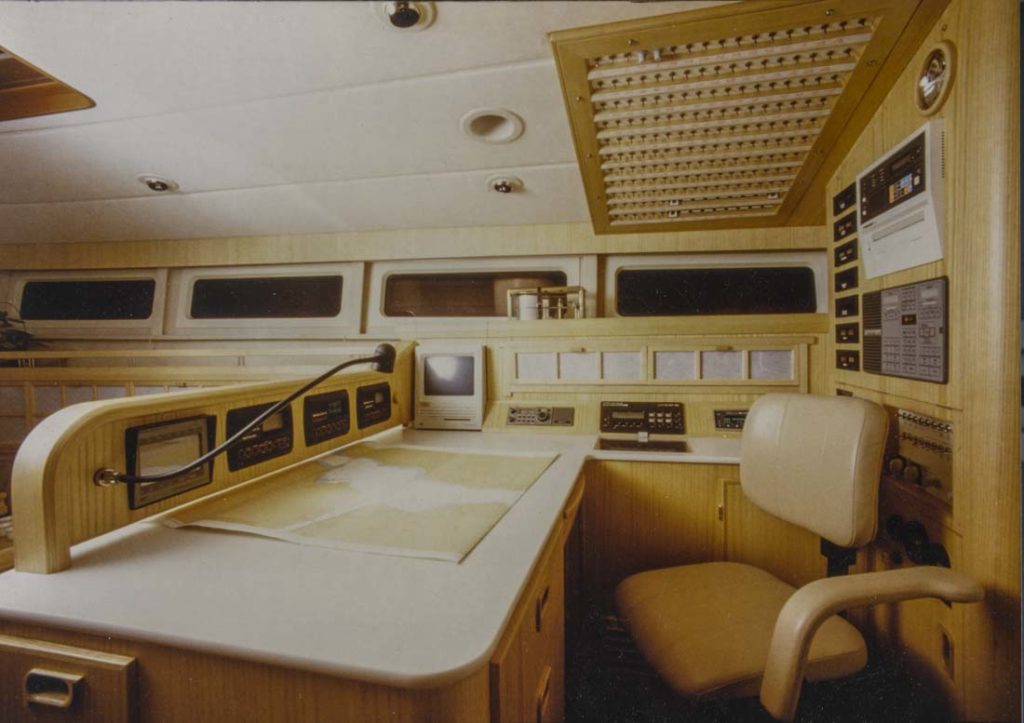

XXXA cool,looking nav station with the main electrical panel overhead. Except there were a couple of problems. First, panel mounting electronics as is shown here for everything means you have a major problem any time you want to change gear. If you are going to panel mount, it is best to use a material that does not fde, and to make extra panels for future use at the same time you are making the first one.

The overhead electrical panel looks good, and is standard in aircraft, but on a yacht it is impossible to reach without standing, and it is not ready to read the labels. We never used this approach again

The interiors of most of the Deerfoot and Sundeer series were the work of Anne and Phil Harrill.

From the preceding you might think that these boats need crew, and in some situations that would be ideal. But with experience and conservative seamanship, they can be sailed by a couple. As an example we offer Interlude. She now has over 160,000 nm behind her and two circumnavigations, more than half of this with her present owners on their own.

Interlude and Moonshadow anchored in Graciosa Bay in the Canary Islands. These two yachts account for over a quarter of a million sea miles between them, almost all of which has been done doubled handed.

Our business model for these projects was a little different than the norm. We supplied our builders with almost all material except for metals, wood, and paint products. Shipments of anything other than batteries and engines came to our house in Ojai, where the garage was both warehouse and staging area. One of the bedrooms was my design office, and another was Linda’s where she did the accounting, research, kept the project notebooks, and followed up with vendors. The telex machine, eventually fax, and big plotter resided in the den. I tried to be in each boatyard every sixty days. It was a compact highly efficient business. Looking back I am not sure how we managed to make this happen.

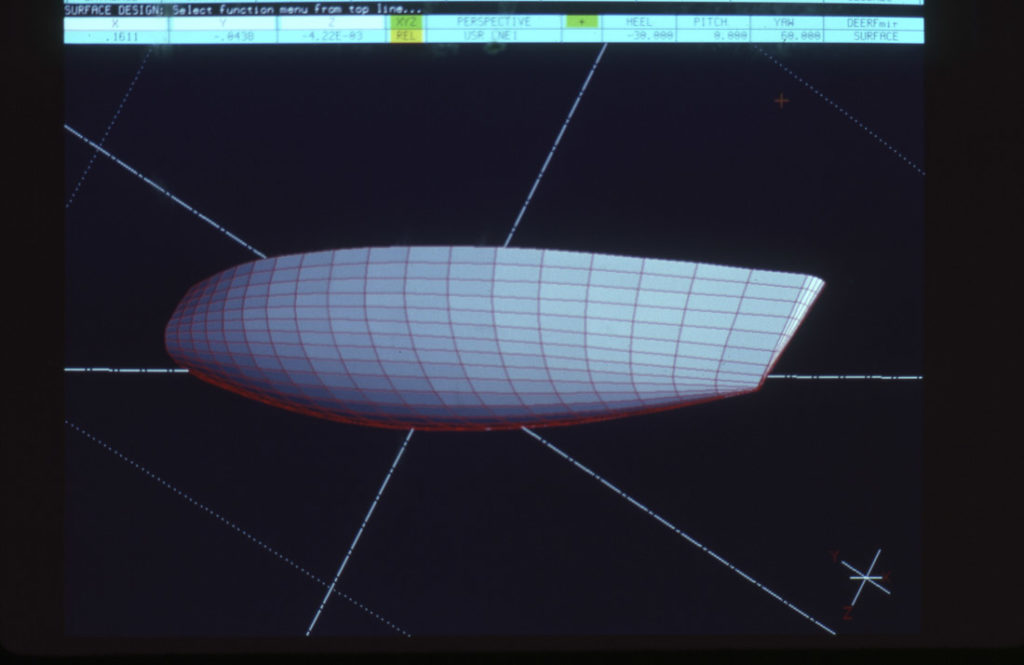

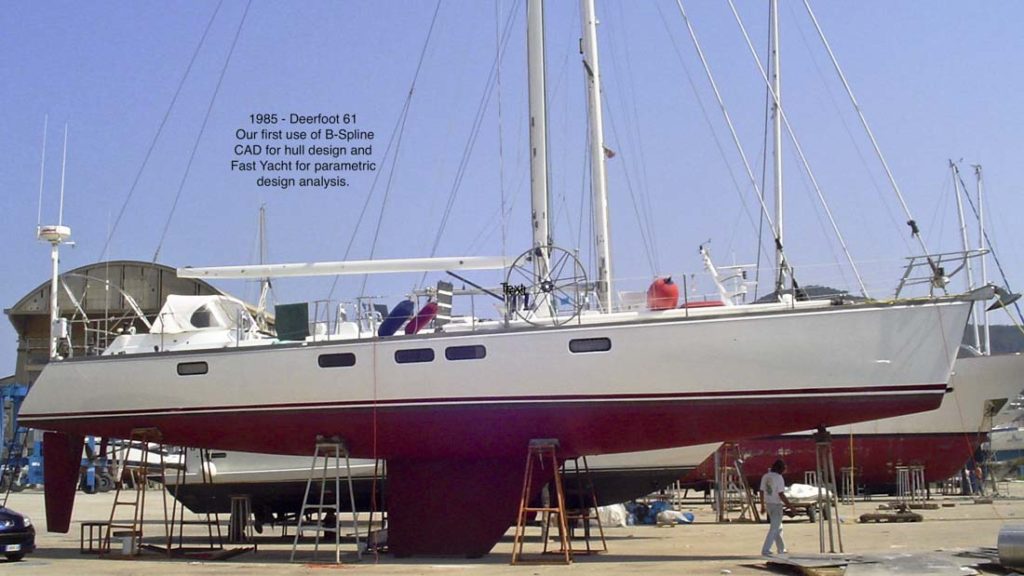

In 1983 we had become aware that George Hazen had put together a suite of software called FastYacht. This included a performance prediction module, keel, rudder, and rig design, and B-spline based 3D hull modeling. This ran on a HP 9816 work station. We had been using George’s analysis services for several years and the ability to use this package for in-house parametric analysis was too much temptation to resist.

In the olden days Linda and I would come up with an initial layout, we’d do a specification and a weight budget, and then have someone do a couple of very preliminary sets of lines. We would eyeball these, think about the various coefficients we thought we wanted, and then went back to the lines drafter to give them a final set of parameters. With 250 or so hours now invested in a hull shape and offset table, everything was thereafter made to fit. The final lead center of gravity wasn’t done until well into the build cycle. Any trimming lead was added after launching.

The Deerfoot 61, two of which we built in New Zealand, was our first project with this new software system. We now had the tools to study all sorts of combinations of rig, hull shape, fins, and stability. Those very simple performance predictions would each take several hours to run. Lines drawing and producing offsets was much faster and we could bring this in house, but overall the time we spent on overall design went up threefold. We would do a preliminary base hull, and then try and come up with something that tested better on the computer. The raw data had to be checked carefully to try and avoid anomalies that might have skewed the outcome. And we had to visualize how the shape would handle at sea.

Sidebar: A little history on the development of Performance predictions programs and CAD marine design tools.

Steve Davis introduced us to George Hazen’s work. After a brief chat with George and Bruce Hays we recognized that the FastYacht suite of tools had the power to significantly help in our quest for the perfect yacht. The $20,000 investment in their software and hardware was substantial, but we thought the benefits made it worthwhile.

Thirty plus years have passed since we began working with George and Bruce. They are still at it. The latest versions of Orca 3D software include some incredibly cool capabilities, things we could not even dream about years ago. It’s almost enough to tempt us back into designing a new boat for ourselves.

As we were writing the comments above we decided to check a few details with George and Bruce about the olden days. If you are into yachting history, there is some interesting information here.

From Bruce Hays:

“The FastYacht hull design software eventually became FastShip. Later we developed the RhinoMarine plug-in for Rhino, based on FastShip. After leaving that company, we developed Orca3D, which George, Larry, and I now own, and which traces its roots directly back to Fast Yacht on the HP 9816 (with the Motorola 68000 processor). In some senses we have come full circle.

Steve Davis was an important customer for the digitizing and viewing software (some of which found its way into the hull design software).”

From Nick Danese:

“Bruce Farr was the first FastYacht customer. I was hired in October 1983 mostly to operate the HP 9816 7” monochrome green screen on which we ran the VPP and to help with appendage hydros and composite structures. We did not use the FY hull modeler because we could not overlay existing body plans (other curves would have been meaningless due to the size of the screen).

We used a digitizing pad, the 9816 ran off a 256k floppy disc (no hard disc) that we had to swap out to load the OS, then the software, then the data, etc. in various sequences depending on what we were doing. A few months later we acquired a double floppy drive, and a few months after that floppies grew to 512 k and double-sided. There was no mouse but the keyboard had a wheel that allowed you to scroll along the line. There was no manual and I was on the phone to George often during the first two weeks or so.

A VPP took 45 minutes or so to run, sometimes longer if the solution would not converge in a well-behaved manner.

The Whitbread Round the World Race trio of USB Switzerland, Atlantic Privateer and Lion New Zealand Enterprise were the first yachts designed using the FastYacht VPP and a home-made RTW normalized statistical course based on Ceramco New Zealand’s log (by Geoff Stagg, by now the Farr office’s racing rep and sales person) and Admiralty Charts, developed by yours truly.

Every subsequent Farr yacht, including America’s Cup ones, were grown through the Fast Yacht VPP.

Some 35 years later i am still working with Bruce, George and, now, Larry :-).

Bruce Hays:

I think you are close on the price, but it depended on whether you included things like the E-size pen plotter (which I recall added $8k-$10k to the price).”“I think Nick’s recollection of the time to run a VPP is pretty close; when I was moonlighting for George, I would go straight to his office from work, get instructions on what needed to be run before he left, and then do the setup and digitizing to get the run started. Then I’d go home and eat dinner, before coming back to do all of the output (polar plots, stability curve, tables of data, and cover sheet).”

George Hazen:

“What a rush to read everyone’s recollections of those early days after I moved my business in town to 222 Severn Avenue, not far from Bruce Farr’s design office in 1981. To be clear, the VPP pre-dated the hull design software by about five years–I originally offered it as a consulting service. This was my principle source of income after leaving C&C in 1979 to 1983 when we first released FastYacht to the public during that year’s Annapolis Boat Show. As you noted, that first release included not only the VPP (I believe we called it a PPP, or Performance Prediction Program), but also modules to help with the design of keels, rudders, spar and rigging sizing, and of course, hull design and fairing. During the nine months or so prior to that first release of the software to the public, Steve Killing was working full-time for me, and among other things was responsible for the name FastYacht and our logo with the sailboat emerging from the stylized HP9816’s computer screen. We had been colleagues at C&C and had recently co-authored a paper for the CSYS on the use of computers in yacht design.

Your recollections about the origin of the VPP were pretty close. It was indeed the subject of my Master’s Thesis at MIT, though I did the work for Jake Kerwin, and not Jerry Milgram. (At the time I was getting my Master’s Jerry was on sabbatical at Harvard studying the fluid dynamics of blood flow I believe.) I paid for my studies at MIT by being an RA on the project that lead to the creation of the IMS Handicapping Rule. Originally, the sponsor was NAYRU (later USYRU), and eventually it was named after H. Irving Pratt, who was a driving political force behind the scenes.

The theoretical underpinnings of the B-Spline-based hull design program goes back to those days as I read all I could about 3D surface modeling in the MIT engineering library. The nine month programming effort that culminated in that first release of FastYacht was perhaps the most productive and creative period in my life, as nearly seven years of research on surface modeling (including three years at a drafting table at C&C) was manifest as computer code. It was a perfect convergence of enabling/affordable computer power, underlying mathematics, and pent up desire. Remarkably, two other individuals on different continents were simultaneously pursuing their versions of similar hull design software packages: Andy Mason in Australia and Marc Pommelet (sp?) in France; MacSurf and Circe3D respectively. Not sure which one of us was first to market, but we all referred to work done by Prof. Dave Rogers at the US Naval Academy. I first learned of their efforts after we released our software in the fall of 1983 when Dave came to our open house.

As to who was the first FastYacht customer, I honestly don’t recall (sad isn’t it), but I do know that you were among the very first to purchase the suite. Bruce Farr had originally used me to run his VPP simulations, but had acquired just the VPP code with its pre- and post-processing components prior to that first release of FastYacht in the fall of 1983. BTW, both Bruce and I moved our businesses to Eastport at nearly the same time. He bought the rest of the FastYacht suite sometime later and we continued to collaborate over the years prior to his retirement. I do recall that despite all of my work with sailboats over the years leading up to the creation of FastYacht, the first hull to be faired with the tool was done as a consulting job for a former C&C colleague, Bruce Kelly, on a large powerboat he was developing. Go figure… It turned out that powerboat hulls and chines were equally well modeled as all of the sailboat hulls I had created. Indeed, you may recall that the original software had (what we would not call) a design wizard – with a very few clicks the user could create an IOR style sailboat that bore a passing resemblance to the then very hot Ron Holland racer, Imp. I have often wondered how many boats were built from that wizard.

As for the Steve Davis connection, that started with an introduction from a printer here in town, George Shenk, who was familiar with Steve’s work. Initially, I would digitize and render 3D wire frame perspective lines and interiors for Steve, but after he left Annapolis and moved out west to Port Townsend, he eventually bought my old 9816 and a digitizing tablet with the software I used for doing the computer renderings. The code that I provided was never offered to anyone else as a standalone tool. The digitizing routines and rendering algorithms had previously found their way into FastYacht, Steve was a real artist, and over the years he used the wire frame perspectives that my software generated to make some truly gorgeous renderings of sailing and motor yachts, and even a few trucks!

By the late 1980s I had stopped personally doing the VPPs as a service, but Peter Schwenn who had joined Bruce and me at Design Systems and Services continued that service well into the 1990s, even after I sold DSS in 1994 to create Proteus Engineering. I recently was cleaning out many of my old job files from those early days and was struck by how many designers worldwide used our VPP: Bruce Farr, Bill Cook, German Frers, Doug Peterson, Bob Perry, Tony Castro, Ron Holland to name just a few. Even the USYRU VPP was derived from one at DSS after I shared the source code written in so-called Rocky Mountain Basic with USYRU. (They translated the code into FORTRAN). The America’s Cup and the US Navy played a big role in the evolution of the software. The name was changed to FastShip in large part because the Navy thought FastYacht was not suitable for the design of naval ships. 🙂 The Navy funded the eventual rewrite of the code into C and its port to multiple operating systems. From that point forward we no longer had to sell the HP hardware that was required to run the earlier versions of the code. The version of FastShip was used by both sides of the competition between the so-called “Big Boat,” designed by Bruce Farr, and Dennis Connor’s Stars and Stripes catamaran. The software was even installed at the sailing venue in San Diego so that visitors could try their hands at yacht design.

I could, of course, go on for some time, because as the lyrics say ‘what a long strange trip it has been’, but those reflections are not really germane to your article.

So in closing, Steve, like you have done in so many other things in your career, I’d say you were ahead of the curve when you saw the promise of our newly released design suite in 1983. It has been a pleasure to work with you over the years and to follow your many interesting marine endeavors.”

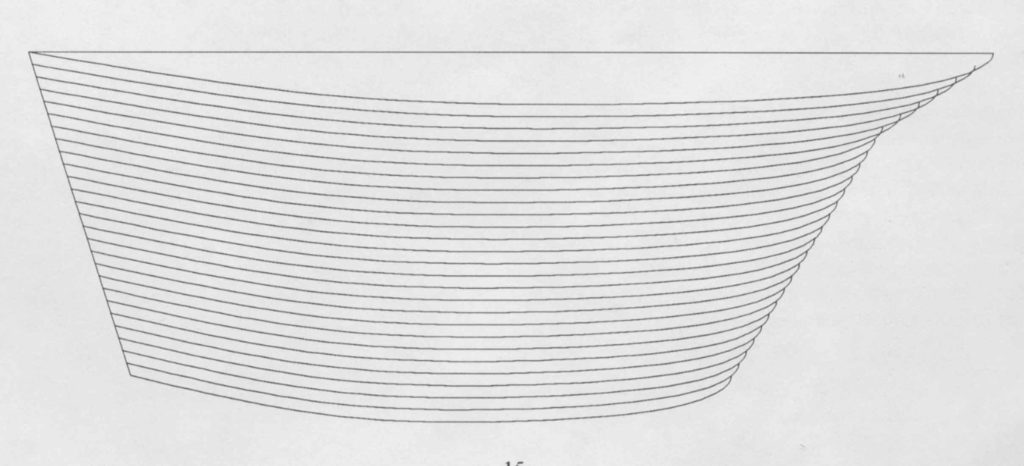

A lovely set of fair lines emerged from this process. We still like this Deerfoot 61 after all these years.

The second DF61 had an extended swim step and eight-foot draft.