I spent my first six decades on earth despising powerboats and those who operated them. In my early days of sailing dinghies, powerboats would always speed up to cross ahead of us leaving a huge wave to wreak havoc with us and our compatriots. My earliest recollection of the single finger salute was from such encounters. As cruisers, if there was a “stinkpot” around they inevitably would anchor close by and then run their genset 24 hours a day. And the lack of seamanship was stunning.

I suspect my negative feelings are not unique within the world of sailors (for a look at our sailing background click here.)

Although I could not rid myself of these hard-etched “stinkpot” images, the design challenge was intriguing. Once we decided to take a preliminary look at an un-sailboat, the first order of business was to investigate what the marketing gurus considered the long-distance archetype trawler. We’d met several voyagers in trawlers, but the logic of the design type failed me. By our sailing standards they were slow, did not have sufficient range to make long passages unless slowed down even further, rolled even when stabilized, were squirrelly to steer, and worst of all were not good heavy-weather boats.

The first person I called was Bill Parlatore. Bill and his wife Laurene had started a magazine called Passagemaker, considered the trawler bible. An ex-sailor, Bill had been bugging us for years to design a long-distance cruising yacht without sails. Bill was our guide to the world of trawlers.

Next, we got in touch with Bruce Kessler. We’d first met Bruce and Joan years before at Catalina when their Zopilote was new. Zopilote was the first yacht built by Delta Marine, based on their limit seiner hull. The limit seiners were designed to rules intended to give fish a better chance at survival. The powers-that-be figured a length restriction would do the job. But they forgot about displacement, and beam. The commercial versions of the limit seiner were massively heavy, tall forward and beamy, but overall with relatively moderate windage. Zopilote was built from the standard hull mold. That they fished in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea tells you something of their seaworthiness. It turned out we had some friends in common, both from our catamaran racing days and Bruce from his youth as the hottest American sports car driver. (The Kesslers went on to circumnavigate aboard Zopilote.)

Then we tracked down Marty and Marge Wilson, who had sailed their Sundeer 64 Kela around the world, and then gone around again in a Nordhavn 62. Marty was our best source of data as we had a common reference point in the Sundeer. An example of how the Nordhavn worked came from Marge’s comments on fridge and freezer door design. On their Nordhavn 62 using the fridges at sea required two people, one to hold open the door and a second to dig out the food.

Finally, another circumnavigating Sundeer 64 owner, Ron Teschke, provided further insight, in particular about heavy weather. Ron had purchased an early Cape Horn steel trawler, intending to cruise Chile and the Antarctic. After being caught in a moderate mid-Atlantic storm of 50 knots he felt they’d been lucky to survive and sold the boat.

Our goal was to try to understand trawlers. Was there some hidden mix of ingredients that made them suitable, or was this marketing hype? In the end the trawler was too slow for us and the places we liked to visit. The other issue, related to speed, was heavy weather capability. We’d seen too much over the years to feel comfortable crossing oceans in a yacht that would not recover from a capsize or be able to run in big seas surfing under control.

FPB 83

This first FPB, the 83’ Wind Horse, was developed as a retirement project for ourselves. We had no intention of taking the concept commercial. Wind Horse was seen as a radical departure from the norm by the establishment, but she was really just an extension of what we’d been doing for years under sail, minus the rig and need for hull form stability to carry sail. (Hence the term unsailboat.)

A short digression into naval architecture. When you have a ship, yacht, or fishing vessel that begins the design cycle with the need to maximize volume or cargo carrying capacity, the hull shape into which you are forced starts life with lots of stability from the hull shape required by the need to maximize said volume. This brings with it a quick rolling motion, uncomfortable on a yacht and dangerous to crew and cargo on a larger ship. The answer is to adjust the vertical center of gravity for the proper motion. Almost all commercial vessels have the ability to raise their VCG with ballast tanks as cargo is loaded to avoid excessive transverse stability. There is only one problem with this from our standpoint. As the VCG is raised to slow the roll period, ultimate stability is reduced and the ability to recover from a capsize is lost. Most motor yachts and ships will not recover from a knockdown of more than 55-65 degrees.

While the preceding paragraph has a certain negative connotation for the experienced cruiser, it is about to get worse. If you are abeam of a wave or swell system that has a period which is a harmonic of your vessel, let’s say a 16-second swell with a ship that has an eight second natural period, a series of seas can quickly induce huge rolls, which may lead to all sorts of dire consequences including capsize. This is known as harmonic rolling. You can see examples in exposed anchorages where very small waves can get some of the yachts rolling like crazy while others just sit nice and still. The rollers are those with harmonic issues. Change the wave period and different yachts will start rolling. As long as you can control the direction of travel, you can avoid this problem by changing course. But if you are disabled drifting beam to the waves, a harmonic situation can quickly become catastrophic.

Coming up with a solution that had high ultimate stability and the ability to recover from a capsize was the first design hurdle we had to clear. By itself this is not difficult. Doing so comfortably, in a configuration that would keep us cruising, was an entirely different story.

Early on we came up with a configuration similar in hull layout to our sailboats: large forepeak now for ground tackle and the many items a cruising yacht needs to store for quick access; engine room aft, with living area centered around the pitch axis. In order to achieve sight lines as well as a nice view the great room was raised, thus creating a basement. The basement was perfect for batteries, a second freezer, air conditioning gear, electronic black boxes, and fuel plumbing. It also provided easy maintenance access to stabilizer coffer dams, and of course storage for supplies not appropriate in the forepeak.

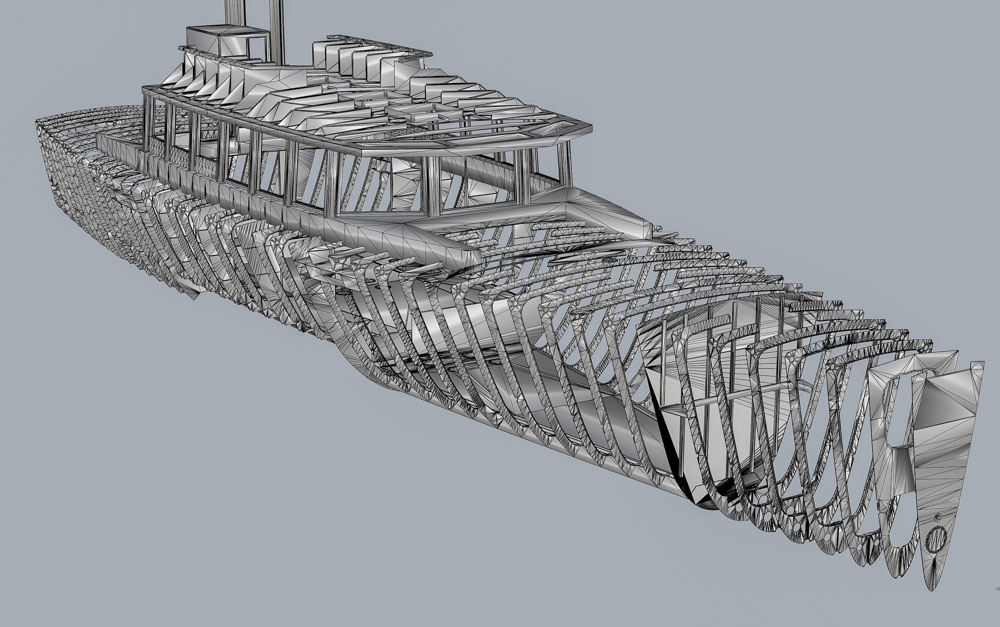

At first glance the process that lead to Wind Horse might seem easy. How hard could it be to modify the lines for a little more mass and different centers of gravity? Computers make the drawing and calculations simple and fast, right? Even though by now we’d been through design cycles numerous times, we badly underestimated the time and energy that would be required to tease that first FPB into being.

Our parametric approach to design projects was simple on the surface. Create a baseline weight, with a first generation interior layout. Use this and the specification to find a weight and center of gravity that experience told us was realistically attainable. With this as a foundation the next step was a series of first principle design hull families, each varying in its overall concept. Then we would do a round of VPP testing on each to see how the drag/power relationships looked.

The hardest part in all of this is understanding motion. How a given hull shape reacts to the sea is a highly complex issue. And not one easily reduced to a tank test, or using computational fluid dynamics (CFD). The sea is simply too chaotic an environment to be accurately modeled. By the time we started the Wind Horse design process I had well over 100,000 sea miles behind me. Most of my time on watch was spent spent trimming sails, checking weather routing options, and studying the interaction of hull and sea. For me the watch-standing process required total concentration to a point where I would not read, watch movies, or even listen to music.

During each hull design cycle when I look at the hull shape, seeing it in sectional layers on the computer screen, I put my imagination to work. With the computer design software we have used the past 20 years it is easy to compare hulls at different heel trim conditions.

An early heeled view above of what would become Wind Horse above. I also rely on the look of traditional lines plans and the feel of 3D scale hull models of previous shapes we have built. I am not sure if the process is intellectual or intuitive, but I can almost feel the hull moving through the water.

With each step along the design path I write up evaluation notes. I try and be as detailed as time permits. Often a family of hull shapes that had previously been discarded becomes the basis for a new look with different parameters. Notes are also made for the goals of the next step in the cycle. The notes are absolutely critical to not losing the design thread.

Periodically we check heeled lines of floatation for downflooding risks. Wind Horse above at full load. Note how the offset entry door is above the 90 degree heeled waterline.

Midway through this process we were confident that we had a design that would keep us safe. How comfortable it would be, compared to our sailboats, we would not know until we’d actually built a boat.

We have mentioned center of gravity a number of times. Control of weight, both as to total and its location, is critical if you want a performance sailing yacht. This is equally important for achieving the desired stability curve on a motor yacht. Working up a detailed weight budget with most builders is an exercise in futility. Unless they are used to building performance sailing yachts, weight will begin to creep into the equation in many areas. The trick is to have sufficient factors of safety tucked away in your weight budget to allow for the inevitable, but at the same time press for the optimum outcome.

While tracking weight you also need to carefully manage polar moments. Polar moments involve the location of the mass, its distance from the center of rotation, and acceleration factors. Concentrated polar moments reduce motion amplitude. On occasion you want just the opposite.

We looked at several hundred different design configurations before making a basic choice. Once a basic hull form family is chosen, the next step is to further refine this as other aspects of the design evolve. This results in several hundred more hull shapes. While this is going on, propulsion systems, drive line geometry, tankage, and a host of other issues like allocation of space, dinghy handling, etc. are also being looked at. The weight, mass and polar moments of the overall boat are constantly being upgraded. There are lots of balls in the air, and it demands total concentration. The Wind Horse design took over 4,000 man hours on my part, essentially crammed into 11 intense months. I ate meals at my desk, rarely ventured outside the office, and almost never took a day off. This sort of a process is obviously hard on Linda and the rest of the family. But it allowed me to complete several years’ worth of work in less than a year.

You can watch a detailed video on this process here for part one and here for part two.

Tank testing is a hugely expensive proposition, and fraught with interpretive difficulty. The effects of scale in the tank, Reynolds numbers, make interpolation from the tank to the real world very difficult. Our own experience was that it was far more efficient to use our VPPs, the efficacy of which we were aware, rather than tank testing.

However, with this project we were venturing into unknown territory with unusual design characteristics for a motor yacht. The hydrostatic hull ratios we wanted to use were off the charts in terms of conventional motor yachts. Volume in the ends (prismatic) and water plane in particular, and how these faired into the hull above the waterline, were critical to the comfort and heavy weather goals. Several very experienced naval architects we chatted with warned against the approach being pursued.

Which is how we came to talk with Lee Head. Lee was running the high performance yacht tank testing department for Oceanic Consulting in St. John’s, Newfoundland. This was the premier tank testing facility in the world and used extensively by America’s Cup and Round the World Race programs. Lee had a slow period between the racing programs and would make us a good deal if we could move quickly and fill the gap. This discounted deal cost was still north of US $100,000. Although we would get extensive drag data, in theory corrected for scale effects with a degree of accuracy, what I was really after was to see the bow and stern waves as the model was being towed through the tank. As it turned out, the wave shape and positioning on the hull was almost an exact duplicate of what we experienced with Beowulf. This was a key factor in deciding to proceed with the project.

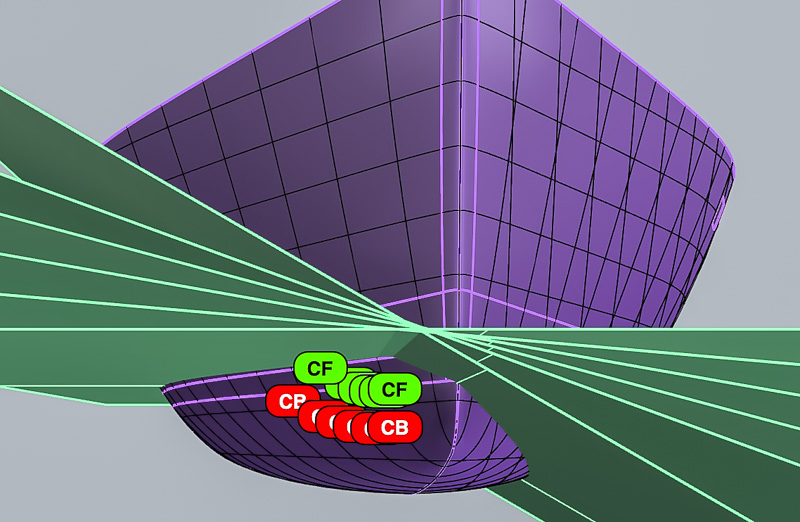

Lee then sold us on a little CFD work. It wasn’t performance data we were interested in, rather what sort of water flow we could expect around the props, rudders and stabilizers in difficult sea states. Various areas of interest were marked on the CFD panelized model and then we watched the movie produced, plus looked at the data to see if we might have an immersion issue with the off-center foils and props (you can see this happening in previously linked videos).

Going uphill things looked fine. But with the seas on the beam the issue could become difficult. As a result of this CFD work we made the decision to steepen the prop shaft angle a bit to get more propeller tip water coverage.

As we have been discussing both transverse (rolling) motion and longitudinal (pitching) motion are a function of sea state, hull shape, and the distribution of mass through the vessel – i.e. polar moments. In order to have the maximum possible chance to fine-tune or change motion, Wind Horse had a ballast tank in the forward five feet of the hull, her flybridge seats could be filled with 2.5 tons of water, and her 25′ long booms were designed to carry up to 750 pounds each at their ends, in the form of lead donuts. We thought the odds were good we’d be sufficiently comfortable without adjusting the polar moments, but the entire project was so new, this insurance was prudent, just in case.

We had been spoiled by Beowulf’s motion. When carrying her water ballast normal heel was rarely more than 12 degrees and she did not roll. Rather, she felt like she was on rails and was far more comfortable at sea than any trawler.

There is a short video with the highlights of a 2000 NM passage aboard Beowulf here.

We did not expect to be as comfortable with the new boat.

Another area in which we were spoiled was with average boat speed. We knew early on that it wasn’t practical to try and equal Beowulf’s 300 mile days in the trades. Still, the idea of switching to an un-sailboat, and thus going slower, rankled me.

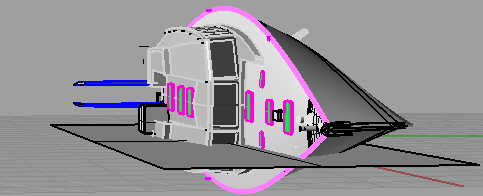

One of the many questions we needed to answer was the appearance of this yacht. We relied heavily on the late Steve Davis for both imagery, at which he was a genius, and for ideas. We started out thinking we wanted it to look like a small freighter.

This gradually evolved into a harder edged military look. We know this was successful, as in almost every country we visited the local officials thought we were military. (Steve Davis was also the main source of illustration for our books and worked closely with us on Surviving the Storm, Mariner’s Weather Handbook, and Practical Seamanship.)

The point arrived where Linda and I had to make a decision. Although we felt comfortable that we had a handle on the outcome, we were both very much aware that we were heading in a direction which was totally different than the industry norm. This represented a major investment for us, and a mistake would set our financial planning back a long ways. We were confident that in an ocean crossing context the cruising trawler phenomenon was based on marketing rather than on design logic. Still, there is always the chance that we’d missed something in our evaluation. In the end, the decision came down to this: the hull shape we wanted to use was close enough to our sailing hulls that the comparable bow and stern waves observed in the tank could be relied on. We had confidence in the speed and fuel burn estimates. The real risk was motion. Sailboats without rigs are notoriously uncomfortable. They have a quick roll and pitch action that is particularly nasty. Could we tune the hull shape and polar moments to get us into an acceptable range? We decided to roll the dice.

We gave Kelly Archer a call to chat about the project, his availability, and that of key employees and subcontractors. We switched gears from design to working drawings.

It has been our habit when working on a project to give it a distinct name or acronym to be used with correspondence and drawings. In this case it came from my constant muttering of “I cannot believe we are working on a f___ing power boat.” So now you know the true meaning of FPB.

Over the years we have built in aluminum and fiberglass for one-off and series yachts and owned yachts of both materials. For sail, where weight and VCG are hyper critical, a case can be made for high tech plastic. And in fact, had we gone with a new version of Beowulf this 80′ ketch would have been plastic.

But with the FPB the huge advantage of aluminum in terms of integral tanks outweighed all other factors. Neither Wind Horse nor the following FPBs would have been possible in plastic. The aesthetic of the bare metal, the functionality, and the ease of fine-tuning are all important advantages of aluminum, but it is the ability to maintain massive fuel and water volumes low in the canoe body that is most critical.

Eventually the day arrived for shipping Wind Horse from Kelly’s shop to the Westport marina in Auckland for launching. Just before she was loaded onto the flat bed trailer Kelly and I placed tape marks bow and stern, indicating our respective guesstimates as to where she would float. Kelly’s tape marks were an inch above mine, representing a 1.75 ton heavier boat.

As had been the case with our sailing designs, there were more than a few “experts” who publicly doubted what we were doing. And to be perfectly honest, we were both nervous, even though we were as sure as one can be that we were on the right path. Still, I was almost sick to my stomach as Wind Horse slipped into the water and the travel lift slacked its slings.

Wind Horse floated even with the top of my tape forward, and between the two aft, almost exactly on her lines. We spent a couple of days at the dock, running equipment, doing last minute projects, and making sure that electronics, steering, and the propulsion system–two 150 HP John Deere diesels–were all operational. The one system we could not get to work was the NAIAD stabilizers. It would be three frustrating weeks until a local hydraulics guru who had formerly worked for NAIAD discovered a temporary pipe left in place from factory testing that needed to be removed and plugged. We’d done our smooth water work-up and with stabilizers active we headed into the Hauraki Gulf that fronts Auckland.

We quickly learned that in the conditions we were testing Wind Horse, now known by the acronym FPB 83-1, was exceptionally comfortable and easy to handle. The learning curve maneuvering with the twin props was quick. And we discovered, much to our surprise, that except for working the dock lines, it made no difference to our cruising ambiance whether it was sunny or pissing down rain and blowing a gale or flat calm. Linda loved the freedom we had to come and go so easily, and didn’t miss the sail handling that had been such a big part of our lives before.

While we were building hours on the systems, trying to find any weaknesses, we often invited friends along for “day sails.” Rather than being bored, I found that there was now time for dialogue with our guests.

Most of the breeze was from the west quadrant, which meant the North Island of New Zealand was a weather shore. We would occasionally find steep seas, but no major ocean swell systems. We were very pleasantly surprised at the motion, as were our sailing friends who came aboard.

Jimmy Schmidt, above, was with us when we had upwards of 50 knots of breeze and came away thinking we might have a winner. The local ferry drivers approved, always a good sign. And when a small commercial fishing boat circled us three times while we were at anchor in the Bay of Islands–we’d passed them the night before off the Whangarei heads in a Northwesterly gale that was kicking up a nasty chop–we knew that we must have something cool.

Normally when we start on a passage we wait for an appropriate weather window. With Wind Horse, however, we wanted just the opposite. We were looking for a post-frontal gale, where a big SW swell set would be crossing NW wind waves at right angles, setting up a wicked sea. We wanted a chance to see how Wind Horse worked in these conditions so if there were any problems we could turn around and come back to New Zealand, where we had the infrastructure to make modifications.

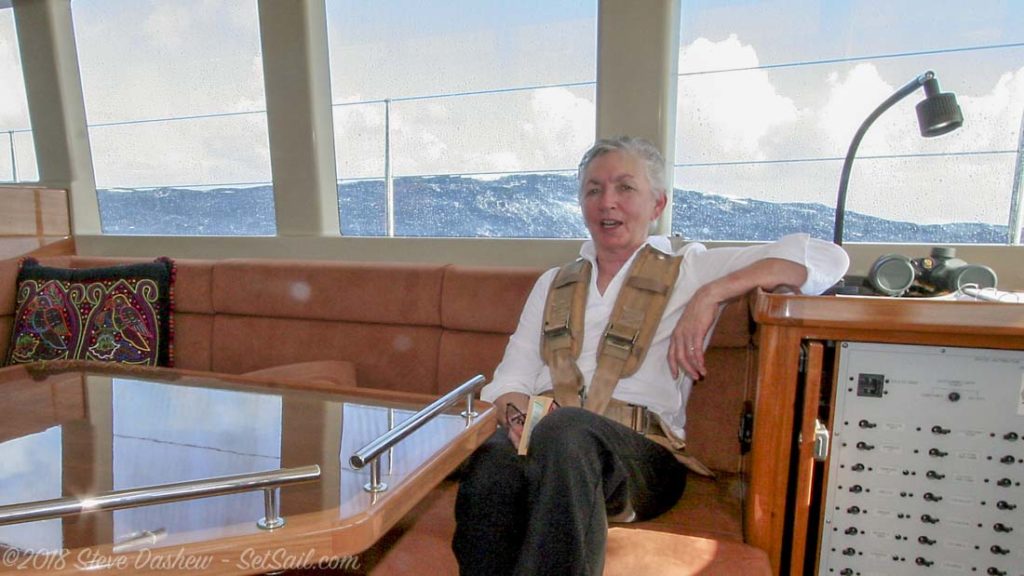

The conditions did not disappoint. Seas in the 12 t0 20′ range with occasional 30-plus footers (shown above in the background) were just what we’d hoped for. Wind Horse stunned us with her comfort. And after the first squall came at us ripping spume off the crests and Wind Horse did not react, we knew we had made the right decision.

The stability curve eventually chosen while comfortable (and therefore “soft) in its initial range, stiffened rapidly compared to other motor vessels. Its point of maximum stability was beyond the minimum angle of almost all other motor vessels. The advantages in heavy weather in regard to “skid factor”, capsize resistance, and recovery were what gave us confidence in the heavy weather capability of Wind Horse.

A corollary was that recovery from wave impact was extremely quick, so much so that if we were sitting to windward, the rapid return to upright could throw us off the seat and across the salon. Hence the seat belt Linda is modeling. They are rarely required, but we have fitted these to every FPB. These were made for . us by Hooker Harness, a company that specializes in aircraft safety belt. In the salon we used aerobatic harnesses, similar to what I used in my aerobatic glider. Bunks had a double pair (for chest and thighs) of conventional lap belts.

And then the breeze backed to SE and Wind Horse began surfing and all was good. You can see a short video of this passage here.

I love this photo of Wind Horse’s bow clear of the water while surfing. This was not anticipated. The FPB 83 hull is much finer forward than our sailing designs, and more deeply immersed, factors which contribute to her soft motion compared to what we had been used to under sail. The fact that the hull was generating sufficient dynamic force forward to raise the bow at speed was an unexpected bonus.

A remarkably flat exit flow of the stern for a displacement motor yacht, this is what we were used to seeing under sail, and exactly what we saw in the towing tank.

The normal route from New Zealand to Southern California was via French Polynesia, using weather “convergences” to make quick reaching passages to the Marquesas Islands. With the upwind capability of Wind Horse established we had decided to return via Fiji, Tonga, the Line Islands and then Hawaii, essentially dead to windward from Fiji onward. The initial legs were easy. We expected more of the same for the final leg.

The passage back from Hawaii to the mainland is usually easy. Go northeast for a couple of days, through the center of the high, and then surf the final third of the trip downhill to the destination.

Except this year the high was centered well north of normal and we would be coming under the center. This was 2,200 miles uphill against the trades. A friend was getting married and it seemed like a hassle to park the boat and fly to the mainland. So rather than waiting for the high to drop, with the capability directly into the seas that Wind Horse had already demonstrated, we did not think twice about getting underway.

The Gulf of Alaska was busy pumping out big swells from the northwest. Every couple of minutes these would cross at just the correct interval with the NE wind-generated waves to create a solid wave peak on the bow. Slowing down did not relieve the resulting thump, so we maintained our pace. We averaged 11 knots for the passage, all but the last day of which was in this aforementioned unpleasantness. At the time, with a standard of comfort defined by our sailing experience, the passage was no big deal. But comfort is relative, and soon we were used to the Wind Horse norm. We became, well, soft.

We were still uneasy about the concept of cruising without sails but we both loved the flexibility Wind Horse gave us. Two quick trips from Southern California to Alaska followed, the second of which had us into Southeast Alaska in early May, a month ahead of normal, and on to Prince William Sound by the first of June.

Even though FPB 83-1 was our final cruising yacht I continued the habits of the past and spent most of these six thousand miles watching how the hull and waves interacted. At first it was to try and understand why Wind Horse was so comfortable. And then inevitably what could we do to improve.

FPB 64

We’d retired from the boat business with the launching of Condor, a cousin to Beowulf. During our two spring and summer cruises to Alaska we had met Todd Rickard at his boat yard on Lake Washington, in the heart of Seattle. Todd was looking for a change and I was in an always dangerous period of boredom. One thing led to another and before long Linda and I had worked up the FPB 64. The real driver in this was the desire to put what we’d learned with FPB 83-1 to work on a new design.

Although the The FPB 83 Wind Horse and the FPB 64 looked similar, and had comparable flying bridges and interior layouts, the hull shapes were totally different. Where Wind Horse had been developed from our sailing experience, in particular the hull shape, the FPB 64 was based on what we’d learned from the 30,000 nm we’d put under Wind Horse‘s keel. In particular was the distribution of the bow and stern volumes, both above and below the waterline. The goal for the FPB 64 was more uphill comfort. Although Wind Horse was a spectacular performer in this regard compared to sail, having grown used to this new level of comfort we now wanted more.

![]()

One of the major balancing acts when designing a hull for upwind performance in waves is the avoidance of a bow that locks in when heading downwind at speed. (Ivor Wilkins took these shots for us just before FPB 64-1 Avatar departed New Zealand for Fiji. She is fully loaded and a steep sea is running in the tide against wind conditions.)

![]()

This is a comfort and speed issue as well as the ultimate arbiter of storm tactics. Unless you have designed a similar type and know its sea-going characteristics, the real world outcome of this process is far from certain.

In this, as in almost all other aspects of yacht design and construction, there is simply no substitute for real world experience. Feedback from others, secondhand experience, does not get the job done. If you are considering a career in the yachting industry our advice is to first go cruising, on your own boat or as crew. Your work product will be better and your clients will thank you. Note that the emphasis here is on long term sea-going experience. Crossing an ocean and then flying home for your land base only gets you partway towards the experience goal.

![]()

Todd came on board on a tentative basis to deal with the clients, should any arise, leaving us free to concentrate on design and R&D. For the period we worked together he was adept at handholding and customer training. The photo above is a favorite, Avatar again, but now surfing. Much more fun than going uphill.

![]()

The FPB 64 interior was based on what had worked so well for us with Wind Horse (you will find hundreds of photos and details on the FPB 64s scattered throughout SetSail.com). We were pleasantly surprised at the quick acceptance of the FPB 64, and eventually 11 of these yachts were commissioned.

The 20 meter/65′ rule that led to the length decision on the FPB 64 forced us to design to a swimstep that would have benefitted from another three or four feet of length. After watching the first two FPB 64s during their sea trials we decided to look at a bolt on extension. A quick study indicated as much as a three percent gain in speed/range. However the benefits were substantially greater, which while pleasing to all left me with bit of discomfort as I could not figure out why the variance. Then one day while walking through the Circa shop with Ed Firth we stopped to check something on the FPB 97 being built alongside a FPB 64. As we turned to go back to Ed’s office my eye ran down the aft end of the FPB 64 hull. Something did not look right. Ed sheepishly admitted he had designed a different extension that was easier to form. It also turned out to be more efficient. Conundrum solved.

And now back to our own cruising.

It is worth repeating that what we loved most about Wind Horse was the flexibility in planning and destinations we now had. Between the comfort and easy handling, the 11-knot average speed, and 4,000+ nm range, we did not have to worry about crew, even on long passages. When fancy struck, all that was required were a few trips for supplies, top off the fuel tanks, and head out. Take January of 2008 for instance.

Our brief experience the previous summer on the outside of Baranoff Island, with its beauty, desolation, and challenges had been gnawing at us. We wanted more. We started thinking about where to go and Greenland popped up. The passages to cover the distance between California and Greenland were easy. Panama was 12 days, almost all of which was downhill. Panama to the Bahamas was another four or five days.

The Bahamas to Nova Scotia another four days. And then several short hops through Nova Scotia, Bras d’Or lakes, and then up the Straits of Belle Isle. The trip from Labrador to Greenland was just three days. So, 30 days, done very comfortably. We spent a couple of days thinking about it and then we were ordering charts, and doing a haul-out for an early preventative service on the stabilizer seals.

We’ve written extensively about the amazing experience we had in Greenland so we won’t bore you with a repeat. The key thing we want to stress is the wonderful options Wind Horse was giving us, precisely because it was an un-sailboat. Wind Horse was much easier to handle than any of our sailboats, was more comfortable at sea, cost less to operate, and extended the range of weather we found conducive in which to cruise.

Where to from Greenland? Never having cruised the British Isles and Europe, they seemed a logical next destination. Except in the summer of 2008, the North Atlantic was misbehaving and storm fronts were more severe and more frequent than usual, typically offering headwinds for the relatively short 1500 nm trip from Greenland to Ireland.

The passage across the “Pond” is a good example of where speed comes into play. We departed the Prince Christian Channels in southeast Greenland on the heels of a massive double low storm system that covered the entire North Atlantic. Taking advantage of the weather “lull” which followed this storm system, we had mainly northwest to southwest flow and had a very comfortable and quick passage. Six hours after securing alongside in Kinsale, Ireland for formalities with Irish Customs it was blowing 55 knots from the SE, right on the nose of our previous course.

While in Ireland we made inquiries as to where would be a good spot to lay up for the winter, and Berthon was one of the yards mentioned.

The quote for the haul, winter storage, and launch sounded reasonable, and on a lovely fall day we worked our way up the channel to their Lymington marina. This being our first experience with winterizing Wind Horse it took three days for us to put her to bed. During this process we were introduced to Sue Grant by Ghillie the Labrador retriever. Although neither we nor the Berthon team knew it at the time, this was to prove a fortuitous meeting. We were very impressed by the facilities, efficiency, skills, and general good humor of the Berthon crew.

We refer to our cruising as R&D, which is the best way we can think to describe it. Our entire design, specification, and build process is formed by our actual experience. Our obsessive compulsion with small details, which drives both builders and ourselves crazy, is based on experience. We would be happier if we had it in our nature to accept a suboptimal outcome. Being acutely aware of what can happen when something does go wrong forbids this approach.

The more you cruise the more you realize reliability is the goal above everything else.

One of the keys to this is having good access to your gear, especially mission-critical systems. If you can easily inspect equipment then you will naturally make inspections at more frequent intervals. This reduces failures. Buried gear tends to be out of sight out of mind. In this regard power boats are more critical than sail, as powerboats typically have more complex gear than sail, and are more dependent on this complicated gear.

In the spring of 2009 we called Berthon and asked them to get Wind Horse ready for launching. The work order included giving the topsides a quick grind using 3M ScotchBrite abrasive discs, pressure washing the exterior, cleaning windows and stainless and dusting the interior. Four days after launching Wind Horse we were off to the Channel Islands. The Berthon crew were stunned. Normal cruising yachts the size of Wind Horse invariably have six figure yard invoices after a winter of maintenance projects.

We spent a month in London, then cruised the West Coast of Norway as far as Tromso…

…from where we hopped across to the Svalbard Islands…

…eventually doubling the mystical 80 degree latitude line.

Magdelena at the north end of the Svalbard group above. We returned to the UK for another winter at Berthon via the Shetland Islands…

…Scotland and southwest UK coast. Then we had to make a decision: do we go back to the US via the North Atlantic, or take the fall route from the Canaries to the Caribbean? We decided on the latter as it was the 25th anniversary of Jimmy Cornell’s ARC.

One of the things we love most about our chosen field of endeavor is meeting up with our family of yachts and their crews. Above we are anchored in Graciosa Bay in the Canary Islands, with Deerfoot 2-62 Moonshadow and the Deerfoot 73 Interlude anchored nearby.

We had an uneventful crossing from the Canary Islands to St Lucia in ten days and eight hours, an average of 11.2 knots for the 2775 nm passage.

Wind Horse at cruise speed approaching St. Lucia. Note the relatively shallow bow entrance forward (by powerboat standards).

We are used to slipping into harbor quietly at voyage end and were stunned by the reception.

A day in St. Lucia to pick up prospective FPB 64 owner Pete Rossin and we were off to Florida. Wind Horse was secured alongside in Fort Lauderdale as the first of the ARC sailboat entries made St. Lucia.

Pete Rossin is typical of the clients we have worked with over the years, An engineer and instrument rated pilot, Pete is highly experienced at sea. Pete had seen Wind Horse do her thing in an English Channel gale. The Rossins put 30,000+ miles on their FPB 64 Iron Lady in a few short years, and now have one of our FPB 78s (on which much more later).

At the end of 2011 Wind Horse had six years and 50,000 miles under her bottom. We were looking for a spot to do a thorough check and refit, which is how we met Corey and Angela McMahon and their Triton Marine crew in Beaufort, North Carolina. Exhaust and salt water plumbing hoses were replaced, the stabilizer system was serviced, and all pumps were replaced with their spares. We also went to a lighter, simpler exhaust system and enclosed the flying bridge.

We rented a nearby house and Chris, the son of Jaja and Dave Martin, gave me a hand on some of the projects while Corey did the brunt of the work. Linda returned to our land base in Tucson. Which is why the FPB 97 came into existence.

FPB 97

Evenings in a quiet house, on my own, lead to idle thought, which invariably turned to yacht design. Just for fun I began to play with an idea. What was the largest yacht Linda and I could cruise aboard on our own? The FPB 97 was the result. Not long into this process we had a call from an interested party in New York. He flew down to meet us, visit Wind Horse, and look at our preliminary design. Shortly thereafter we had a contract to do a new boat. The preliminary design was easy; now there was real work to do.

Steve Davis’s untimely demise left me without a valued resource. Some years before I had received an e-mail from a young illustrator offering his services. At the time, we were covered. Luckily I was able to find that email and got in contact with Ryan Wynott. Ryan did a few two-dimensional renderings for the FPB 97 project and it was obvious he had talent. I asked him if he would like to learn 3D using Rhino and Orca software to which he replied in the affirmative. We worked closely on the 97 and subsequent FPBs and Ryan’s skill in 3D grew quickly.

That realistic looking FPB 97 surfing is actually a rendering.

You can see by the renderings above that Ryan’s skills were progressing.

What intrigued me about the FPB 97 project was the ability to use Wind Horse as a scale model of the new design. Towards this end we added three feet to her swim step, and then had the already small diesels derated from 150HP to 110HP each. With these two changes Wind Horse, now 86′ long on deck and 83′ on the waterline, would do in excess of 13.5 knots at half load in smooth water. Using a pair of the 230 HP six cylinder diesels in the FPB 97 showed us 14.15 knots. We doubted anyone would believe that this was possible and we followed the same approach we had used in the past and substantially under-predicted (you might say sandbagged) the performance we told everyone to expect.

As the build progressed it became apparent early on that we were going to have a weight issue. This, of course, is not an unknown phenomenon in the yachting business. As an insurance policy we had drawn the hull shape so it could be easily extended. The owner understood immediately the benefits of added waterline in terms of deck space, working on a bigger swim platform, and efficiency.

The FPB 97 grew to 110′ overall. When this yacht went into the water, in light cruising trim, FPB 97-1 exceeded fourteen knots during trials. More important, in cruising trim 11.25 knots could be maintained in most passaging states. The prop shaft and exhaust systems were conservatively engineered and when her owner began to think about the desirability of a faster cruising speed, he was able to fit a pair of 450 HP engines using the same shafts and exhaust systems. With these bigger engines he still had trans-Atlantic range at 14 knots.

In the spring of 2012 we decided on another leisurely cruise to Maine and back, duplicating the previous year. We particularly enjoyed the gunk-holing in Maine, the more rural parts of the Chesapeake, and the Intra Coastal Waterway. The sub-five foot draft of Wind Horse was particularly beneficial in the latter two cruising areas. In seven years of part-time cruising, Wind Horse had taken us over 60,000 NM. We were now in our 70s, there were a couple of health issues that had us concerned, and frankly, we thought it might be time to try something else. We had not previously considered selling Wind Horse but started to think about the prospect. A few months later we were in the Bahamas and were asked if she might be available. In a moment of weakness we agreed to sell her.

FPB 78

It took two weeks before we began to wonder if we had made a mistake. At four weeks I began to sketch, At six weeks I was chatting with several FPB 64 owners who were interested in going larger. By eight weeks we were into another full on design cycle. Between Wind Horse now at 86 feet and the FPB 64s also extended to 69 feet LOA (with a bolt-on removable swim step addition) we had a good sense of where we wanted to go with hull shape. Our goal for this design was to develop sufficient space to carry crew if desired, and provide enough volume so we and they could have a bit of separation. This meant adopting the FPB 97 interior arrangement and foregoing the basement. We chose the larger FPB 78 for our personal use because we felt it would allow us to continue cruising as maturity made taking crew prudent.

Looking back, the combination of an extensive powering database from our sailing designs, CFD and VPP analysis, coupled with tank testing, meant that there were no surprises performance-wise with Wind Horse. As mentioned earlier what did catch us unawares was the huge increase in comfort. We were used to very fast passages under sail, with little of the motion that ocean crossing motor yachts tend to take for granted. With Wind Horse, the incredible comfort was a great surprise. Except for one thing…We don’t like surprises. We have since spent most of our sea time with FPBs over the past 12 years–70,000+ nm now on our own bottoms–working out what it was that made the first two FPB designs such sweet passage-makers.

There is a design tension between a hull configuration that is comfortable heading into the waves, one that surfs downwind under directional control, and avoids the bow “locking in” when charging down a wave face. In comfort and safety terms, downwind control is important in both heavy weather and normal downwind passages. If the hull does lock in and begin to “bow steer,” or the stern gets pushed around by the wave, the next step is a broach.

Although the FPB Series look similar, each hull is its own unique blend of design elements. These vary with length of the hull and the wave size and period for which they are optimized. Wind Horse above showing off her wave piercing bow.

![]()

![]()

Now the FPB 64 heading into a nice sea-state.

And finally the FPB 97. In terms of sectional volume build up the 97 has the finest bow 83 next and the 64 is the “fattest” to this point.

The combination of canoe body shape, deck shear, mass, topside cross section, and anchor position of the FPB 78s is considerably different than the preceding FPBs. The finer ends, increased mass-to-waterline ratios, and higher shear were the subject of more than a thousand hours of drawing, testing, discussions, and over 500 hull variations drawn and tested.

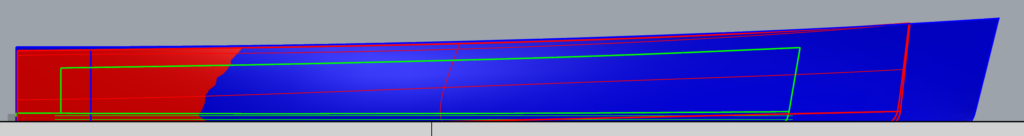

A shear and freeboard comparison between the 64 (yellow/green), 78 (red), and 97 (blue). Note 78’s freeboard and shear forward. The FPB 78’s anchor sits above the deck whereas all previous FPBs had their anchor chocks in line with the belting (rub rail).

But even with all the design tools we have at hand these days, in the end how these elements are blended is very much a result of instinct, honed from our experience. We ended up with a more efficient hull shape at cruising speeds in the 9.5-10.25 knot range, but pay an increasing penalty above this speed compared to a hull which is more like the FPB 83 and FPB 97–a tradeoff all of the FPB 78 owners are happy to bear in exchange for the added comfort uphill and benefits when surfing in aggressive conditions (click here for video of Cochise surfing at 14-22 knots).

A key goal in the design of Wind Horse and the FPB 97 was a target cruising speed in the 11 to 12 knot range. To do this in a hull that did not slam excessively upwind is not easy. Higher speeds require more volume in the ends of the hull to move efficiently, which can be counterproductive comfort-wise in waves. But if we backed off on the speed a touch the hull could be shaped with finer ends, which translated into softer motion. We could always get somewhere quickly if needed by running at high fuel burn rates and throwing power at the increased drag.

The other factor, as always, was steering control. The FPB 64 had a much sharper forefoot with a deeper bite in scale than Wind Horse. Now that we had a series of the 64s out cruising with results observed personally, and the data from the logging systems, we felt we could soften the next generation a touch further by fining up the sectional shapes forward and aft.

Longitudinal stability relative to mass and how this behaves in different sea-states upwind is one of the most important characteristics. The FPB 83 and 97 were at a disadvantage here because of their very high fore and aft stiffness (known as GML in tech speak). The FPB 64’s shorter length and heavier mass and lower GML allowed a more sea-kindly motion uphill. One of the goals for the FPB 78 was to reduce the fore and aft stiffness. Even more critical to comfort and safety is how volume is developed in the topsides above the waterline.

One of the historic designs that gave us confidence to pursue a very different hull form from the preceding FPBs was the 68-foot ketch Sundeer. Her ends were exceptionally fine, and under sail and power Sundeer had a very soft motion up and down hill. In hindsight for sailing we had given up too much performance, and we backed off a touch in subsequent designs. But in an FPB there were no negatives to this approaoch.

The hull shape eventually settled on was quite different from the preceding FPBs. It not only had less form stability at the waterline in the ends, but allowed for substantially more mass in the form of liquid payload, systems, and structure. The distribution of volume was considerably different and turned out more efficient than Wind Horse at ten knots, but less efficient at eleven. No surprise here. Yet given the added fuel capacity we had actually more range at 11 knots. We were so comfortable with range that we took the comfort standards Wind Horse had afforded us even further, undertaking a Fiji to Panama trip against the prevailing currents and trade winds with a single fuel stop at Raiatea in French Polynesia. We would not have considered this in Wind Horse.

As the FPB 78 (in reality 86′ LOA but measuring in under the British MCA rules at 23.95m or 78 feet) evolved we worked closely with two of our FPB 64 owners, Pete Rossin and Peter Watson. Because they now had many thousands of miles of experience with their FPB 64s, and both were engineering oriented, they provided a very efficient sounding board.

Cochise at 11 knots above. Although the bow and stern waves look small, they are larger in scale than either the FPB 83 and 97. They are also closer together. Both of these parameters indicate less efficiency at higher speed. But there was a pleasant surprise when surfing on passage.

Slower in theory compared to the FPB 83 when surfing, the FPB 78 actually averages the same sort of daily run as did the FPB 83 and can be comfortably pushed much faster. There are several reasons for this. The FPB 78s are smoother running and quieter than the preceding FPBs and there is little noticeable change in onboard ambiance between ten and 11.25 knots. The boats steer beautifully in big seas in spite of the deeper forefoot. The only hit comes in pre-surfing conditions where we find we are running .75 knot slower if we want to maximize range.

Take a look at this wake photo, surfing down the coast of Nova Scotia. We are averaging 12.5 knots, surfing to 17, with occasional rides to 20. The secret to all of this is the narrow stern. This is what makes it possible to run at speed in the waves with good steering control, even though we have a deeper forefoot. It is also what makes us so comfortable upwind.

When we started the FPB 78 design we were chasing more interior space, something mid-way between Wind Horse and the FPB 97 Iceberg, within a hull that was similar in length to the FPB 83 Wind Horse. We were also after a layout that allowed us to have crew and/or guests while at the same time providing sufficient volume so that we and they would have breathing room.

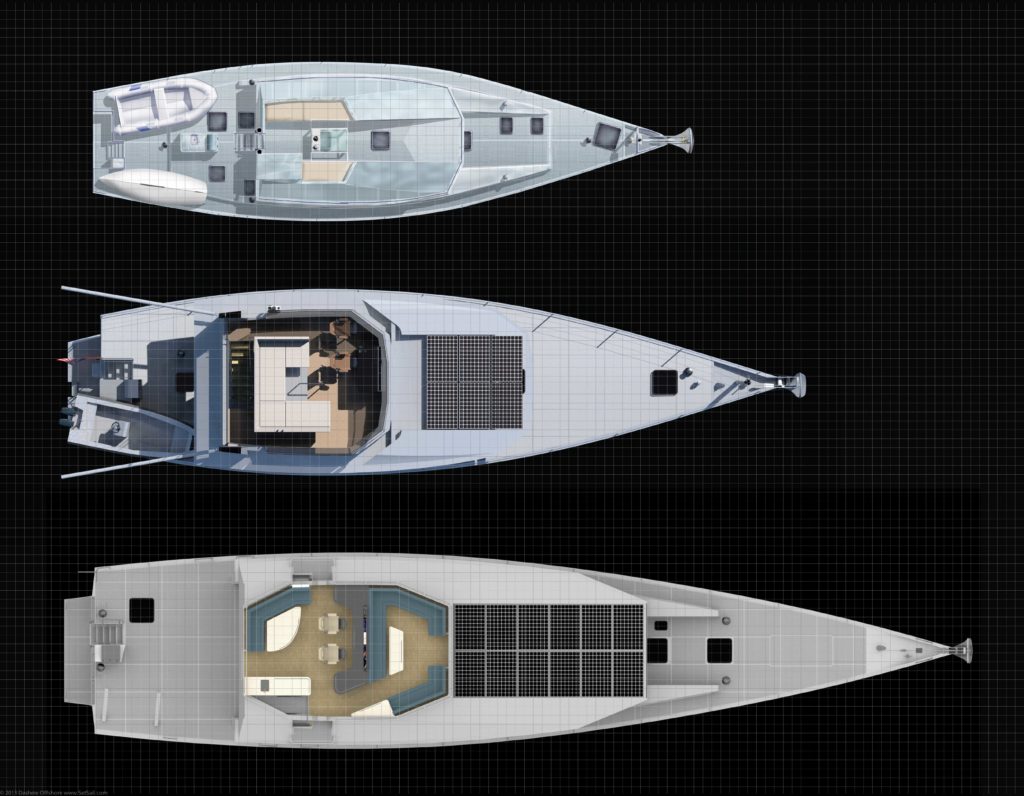

Layout comparisons with the FPB 64, 78, and 97 below. Note that these schematics omit the swimstep extensions that were eventually standard on the three designs.

A deck comparison of the 64, 78, and 97 with cutaway Matrix deck.

Main decks of the 64, 78, and 97 above.

And the lower decks of the same three.

Let’s digress a moment from our focus on hydrodynamics and indulge in a bit of interior scenery.

Looking forward into the great room from the entrance aboard Cochise.

Looking aft.

Of all the galleys we have done Linda likes this the best. The C shape holds you in place yet there is enough room so that two can work within the confines of the galley at the same time.

The connection with the world outside that Linda and I feel in the great room is difficult to capture in a photograph, at least for me. Michael Jones came the closest of anyone with his lovely shot above.

Our quarters are located slightly forward of the pitch center, where motion is minimal and there is just a hint of machinery noise at sea to let us know the engines are purring. The pillows are within 6.5’/2m of the pitch center.

To fit an interior like this meant we needed more height, depth, and beam. The tricky part here was that we would be living and working further from the motion centers of the vessel compared to Wind Horse. If we were going to maintain the comfort level to which we and our clients had become accustomed, this new design had to have a softer ride in absolute terms.

We have always pursued maximum systems efficiency and engineered an approach based on the assumption that the shore power cord was unplugged. These integrated systems combined a mix of batteries, charging capability, ventilation, and air conditioning that allows the FPB 78s to sit for multiple days without running the genset.

Solar power, while always part of the equation, was not a major driver in the previous designs. Now with the data in hand from the FPB 97’s massive solar array, we saw that if we started from day one of the design cycle to organize our systems around a large solar array, a lot of good things would be possible, like solar powered air conditioning. Cochise, shown above, started out with ten panels and eventually ended up with sixteen. If that seems like a lot–they are 335 to 360 watts output each–we would not give one of them back.

Having put 20,000+ nautical miles on FPB 78-1 Cochise in a short period of time, we can tell you that the FPB 78 is extraordinarily comfortable.

The emphasis on uphill ambiance has paid big dividends. This is what allowed us to consider an upwind against the trades passage to Panama from Fiji, which in turn gave us a chance for a third visit to Fatu Hiva in the Marquesas (our favorite tropical anchorage in the photo above) for a day on the way to Panama. To put lovely Hanavavae Bay into perspective, that tiny bit of gray at the bottom of the cliffs, just left of center, is Cochise.

The same can be said for FPB 78-2 Grey Wolf II with a voyage from New Zealand to the Channel Islands between the UK and France via French Polynesia, Chile, Tierra del Fuego, and Antarctica, in a single year. (Simon Lucas photos above and below.)

And with FPB 78-3 Iron Lady II’s trip from New Zealand to North Carolina via Panama, with a little detour to check out Costa Rica, Galapagos, Chile, Tierra del Fuego, and Antarctica. FPB 78-2 and FPB 78-3 cruised Antarctica in company.

These three FPB 78s have a combined total of 75,000 + nm in their wakes since launching.

Cochise above anchored off Raiatea, our only fuel stop between Fiji and Panama.

We don’t want to bore you with our obsession about heavy weather, but there is one more subject we want to cover, dealing with extreme conditions. This is where stability, steering control, maneuverability, and how volume develops above the waterline really come into play. While these are comfort factors in normal conditions, they impact your survival in extreme situations.

Many years ago, while researching ultimate storm tactics for our book Surviving the Storm (free download here), it became clear to us that, whether it was Fastnet ’79, Queen’s Birthday Storm, or the 1998 Sydney Hobart Race, heading into the waves is often the best tactic in severe weather.

Because our yachts surf downwind under control making quick passages, and since in all but one of the serious storms we have experienced our natural course was downwind, we’ve rarely had the chance to experiment with truly dangerous seas on the bow. During a recent trip from North Carolina to Maine we encountered an unusual set of conditions resulting in very steep waves, of which the photo above is an example. And while this experience was far from what we would call a survival storm, the unusual sea state did give us a chance to test several FPB-specific steering and throttle techniques, along with gathering a couple of ideas for improving electronics and night lighting layout. You can read a detailed post on this here.

There are some remarkable photos in that linked post, the result of having recently installed a series of high-res video cameras and related recording gear. Without this we would never have been able to show you what the sea can be like, and why we feel strongly about certain design requirements for offshore voyaging.

Briefly then, Cochise and her crew–the two of us and Corey McMahon–were enjoying a lovely 25-30 knot SW breeze, as we surfed downwind towards Maine from Beaufort, NC. We were headed outside Cape Cod, with a potential stop in Nantucket should our timing make this efficient. Not long after we departed the forecast indicated the chance of meeting a moderate Nor’easter somewhere in the area of Nantucket. A day later two bands of intense squalls, with gusts to 40 knots, torrential rain and lightning announced the arrival of the new air mass. Of course this happened at night.

To us and to Cochise a 40 knot NE breeze, even if against the Gulf Stream, is no big deal. What made this situation different was the occasional head-on collision of SW swells and NE waves in just the right fashion to produce sets of three waves much larger and steeper than the norm. They were more vertical, and seemed to be moving more slowly than would normally be the case for waves of this size. As such, we think they gave us an indication of Cochise’s reaction to the cascading crests in an open ocean storm where the larger but more widely spaced waves have more fetch and time in which to develop.

The roughest part of this situation took place between 0300 and 0600.

The camera for the previous photo is 17’ above the waterline and it is fitted with a wide angle lens. The oncoming crest is steep. Looking at the photo, studying the angles, and knowing the lifeline stanchion top is 12 feet above the water, we guesstimate the approaching crest is in the 20-foot range.

Here is another part of the FPB secret sauce, shown in the photo above, from the same time frame as the first. The stern shows how little it is affected by the passing crest. Any more volume aft and the bow would have been forced down and into the oncoming wave. This plays an equally important part in surfing control, as when headed downwind the immersion of the transom into the wave face gives props and rudders better conditions in which to operate and the wave cannot exert as much force towards upsetting balance or pushing the stern into a broach (more on this below in the Bahamas surfing video)

How steep were these waves? In over 200,000 miles at sea we’ve only twice experienced anything similar. Once was running down the Irish Sea off the coast of Wales. It was during daylight, the bow dropped into a hole and a very substantial crest came rolling down the deck. With a harbor of refuge in our lee it took just that one sea to convince us to change direction and enjoy surfing to safety. The other was at night, between North Carolina and the Bahamas. We spent several hours in what must have been violently confused seas. We never saw them, but it is the only time motion has ever been severe enough for us to be totally airborne.

Corey McMahon, who has circumnavigated, crossed the Indian Ocean twice (once west to east with daily 60-knot blows), and experienced numerous other trans-ocean passages, has never seen anything similar. Corey likened this to a 100-mile long entrance pass or channel with standing waves. He echoed our own feeling that as long as everything worked we were fine. “I would not have wanted to be sideways. Yet I was comfortable enough to sleep on the Matrix deck couch,” he told us afterwards. Corey reckons we were seeing wind at a steady 40 knots at times.

The few seconds of waves here, and the 50-knotter on the way to Bay of Islands during sea trials, capture why FPB hulls look so different from other designs.

Loss of steering, even momentarily would be less than ideal in anything approaching these sea states. The FPB 78s have emergency steering controls at both helms. Pushing a single button puts us in direct control of the backup hydraulic steering system.

The photo above is extracted from a video we made earlier in 2019, crossing a narrow entrance channel in the Bahamas with a strongly ebbing tide against an onshore breeze. The resulting seas were steep and Cochise gave us an excellent ride through the cut using a single wave and carrying it all the way in. If there was ever a time where the bow might lock in, this was it. We maintained precise steering control. Note how deeply the stern is immersed, and how little buoyancy there is aft for the sea to lift against.

The photo above is extracted from a video we made earlier in 2019, crossing a narrow entrance channel in the Bahamas with a strongly ebbing tide against an onshore breeze. The resulting seas were steep and Cochise gave us an excellent ride through the cut using a single wave and carrying it all the way in. If there was ever a time where the bow might lock in, this was it. We maintained precise steering control. Note how deeply the stern is immersed, and how little buoyancy there is aft for the sea to lift against.

Before we leave hull shape in our wake, a few more comments on what happens above the waterline. There are tradeoffs between interior volume and optimum hull shape. The bigger the seas the more important this becomes. It affects sea-going comfort, safety, and average ocean crossing speed. Our approach to this is simple. There are no tradeoffs. We optimize for the ocean.

If we get this right the bow and stern have the right mix of volume to slip into an oncoming wave smoothly, with the bow lifting before the wave crest. Downwind, at high speed, dynamic lift plays a part.

Aside from preparation, the best guarantee of success in passaging is patience, picking the right weather, and using boat speed to avoid bad weather in the first place.

While Cochise began as a design package that would allow us to carry crew, we found that we still prefer to cruise on our own. To do this at our ages, north of the three quarter century mark, forced us to refine several aspects of Cochise which we would have ignored earlier in our careers. All of these refinements made Cochise easier to handle when we are by ourselves, and had we thought about this before we would have adopted these same principles at the beginning of the FPB era.

Our idea of what constitutes a comfortable watch station has changed. We want good hand-holds and/or rails or furniture to hold us in place. The presentation of nav and systems data needs to be easily switched back and forth between modes. In a normal context, our previous yachts had wonderful watch-keeping parameters, and the FPB 78 helms were based on this.

In the great room we started out with our typical nav desk forward.

During the passage to Panama we discovered that the big TV was ideally suited to ship systems and navigation information. It is visible from the forward helm and the galley aft. The vertical screen created less reflected light than the angled monitor and instruments on forward desk. This enhanced our night vision. This discovery coupled with several other factors lead us to reexamine our Matrix deck design.

The Matrix deck evolved to its present form over several years, starting with discussions between ourselves and Steve Parsons (the three of us above in French Polynesia with the original Matrix arrangement) while halfway to Panama about the ultimate Matrix deck layout. Perfecting this took an inordinate amount of time because the approach was so different. Each time we would think we had it nailed down, real world use would show us areas that could be improved. The process was time consuming and costly, but in the end gave us a conning environment that was far easier to use than anything we had done before.

Six or seven years ago we would have been happy with a couple of small displays on the Matrix deck as shown above in New Zealand. Today we are more dependent on the electronic data, and avoiding info overload and the mistakes that are associated therewith required a new approach.

After testing numerous ideas we settled on the use of four 55″ TVs, placed low, against the coamings, with the ability to be angled from vertical to almost horizontal depending on what was optimum for the conditions encountered.

The port screen operates by touch, a joy to use at this size. Harking back to my flying days we ended up with a very compact con, one that makes it possible to operate all nav gear, steer, and control the engines from either helm seat, either standing or seated.

The Matrix area lighting, external lighting, bilge pumps, crash pump, and fuel transfer system controls are here as well as the AIS and VHF radio control heads. Offshore, this works well for a single watch stander. In shallower waters we now pilot Cochise together. Note the six Maretron N2K displays. Although we have this data available via wifi to a variety of tablets, and on the big TVs, these screens always have key data right in front of us. This is easy to find when under stress.

The data displayed on the different screens is infinitely variable. Sometimes the displays will be set up so that each side has similar data, arranged to the liking of the port or starboard seat occupant. In other situations the data arrangement will have separate info on each screen. And in some cases, we will supplement these four large screens with one or two tablets. This system allows to tailor the presentation in a manner that is easily understood, with the least possible interference with our maintaining external situational awareness.

A very important aspect of this approach is that on soundings we typically lay out the screens so that adjustment of the data, say radar range, can be done with a single operation, eliminating the need to change windows when a single screen has multiple windows. Each screen has its own dedicated Simrad controller.

Important side benefits from this approach included improved motion due to the lowered helm seats, much improved sight lines from the helm, whether standing or sitting, and from other seating areas. There were many small details, like the angled soft foam foot blocks in the photo above, that made this area more comfortable.

Cochise is obviously a large yacht, and the openness of the great room and Matrix deck requires some method of containing our bodies at sea. The great room has a pair of removable staple rails (shown above) to break up the forward area, along with a system of overhand hand holds made up from high strength Spectra rope.

The Matrix deck has the overhead man-lines as well.

And then in its final iteration we installed a combination staple rail/table that gives us somewhere to put camera gear, snacks, acts as a charts table, and provides a foot rest for the couch. It is positioned just aft of the helm chairs, so that we are held in place at sea. The passageway can be widened by sliding the helm chairs forward. We can now move from the stairs aft to the helm chairs constrained by structure with a variety of high and low handholds.

We have found the air flow so good in the Matrix deck that the air conditioning was never used. So when we did our last mods we removed the air con unit. The heating system was enhanced with a pair of 2″/50mm hoses that can be tucked into a blanket on a cold watch, keeping us very cozy.

A note on a somewhat delicate subject. We installed a toilet in the aft starboard corner, under a cushion so it is hidden from sight. But open to the world at large when in use.

We reasoned that it was a long way to an enclosed head below, the use of which by the watch would leave the helm unattended for too long a period. When we were removing all of the original Matrix deck furniture we left the toilet in place. It is not used often, but we consider this essential for short-handed passage making.

Maneuvering in Tight Quarters

The FPBs have always been easy to maneuver. The hull shape, huge rudder(s), and prop position relative to the rudder(s) are the keys. The FPB 78s put more thrust into the water in scale against rudders which can be rotated further and turned lock to lock faster than any of the preceding designs. The sum of these factors is an amazing level of control and precision in tight quarters. Although Cochise is fitted with a powerful bow thruster, the tunnel openings have been sealed for almost all of her time afloat.

Still, we were wary of her size the first couple of times we brought her back to dock on our own in New Zealand. But after half a dozen dockings we quickly became comfortable with the size. Compared to Wind Horse, which we thought handled like a dream, Cochise has far more control, will rotate more quickly, and is much easier to dock in really difficult weather/current situations.

Now a few handling details, some of which may be of benefit to others:

- We rig the dock lines and fenders well ahead of time, so that when we are closing with the dock all our concentration can be on the docking maneuver itself.

- Once we have a plan, we discuss what we are going to do and what our fallback plan will be if things go wrong.

- We communicate with headsets and double check that these are working and have sufficient battery capacity.

- Fenders are made ready but we typically do not deploy these until we are at the dock.

- The main deck remote helm control is set into position over the engine room air exhaust.

- There is always one long dock line, flaked down and ready to use if needed, but otherwise unassigned.

- We have both forward and aft spring lines ready to go, typically with a bowline in the end so the loop can just be dropped over a cleat. If we are not sure about help on the dock, a boat hook will readied forward and aft that can be used to drop the dock line loop over a cleat.

We then get in close to have a look at the area, if we have not already done so with the dinghy or by car. The FPB 78s respond well to both bow and stern spring lines (assuming they are correctly placed). With the spring line on the dock, all we need to do is pull against it gently, with the rudder deflected to bring the end of the hull against the dock. Even in a stiff breeze off the dock we have found this method quite effective.

Linda talks me through what is happening at deck level. She lets me know that she has handed the spring to someone on the dock and what they are doing with it.

Once the spring is secured and the boat begins to pull against it, I walk down to the main deck and resume controlling engines and rudders from the remote set of controls. This way there are two sets of hands to finish securing to the dock.

The anchor platform is wider than in the past and allows us to walk out to the very tip of the anchor. In really difficult situations we will sometimes bring Cochise in bow first, pinning the anchor against a piling or wall, or the cutwater against a dock. This holds the boat in position versus wind or current and allows time to get a pre-rigged breast or spring line onto shore.

There are Lewmar 65 self-tailing kedge winches forward and aft, that are positioned so they can be used with dock lines.

The big kedge winches are very helpful when anchoring with the stern to shore, as shown above in front of Laureen and Bill Parlatore’s home near Annapolis. Anchoring like this tests the boat’s controllability to the limit.

Another challenge is sneaking through a slalom course of lobster pot buoys. Great fun, this is.

A relatively easy, OK boring, docking challenge. After all, there is lots of space on each end.

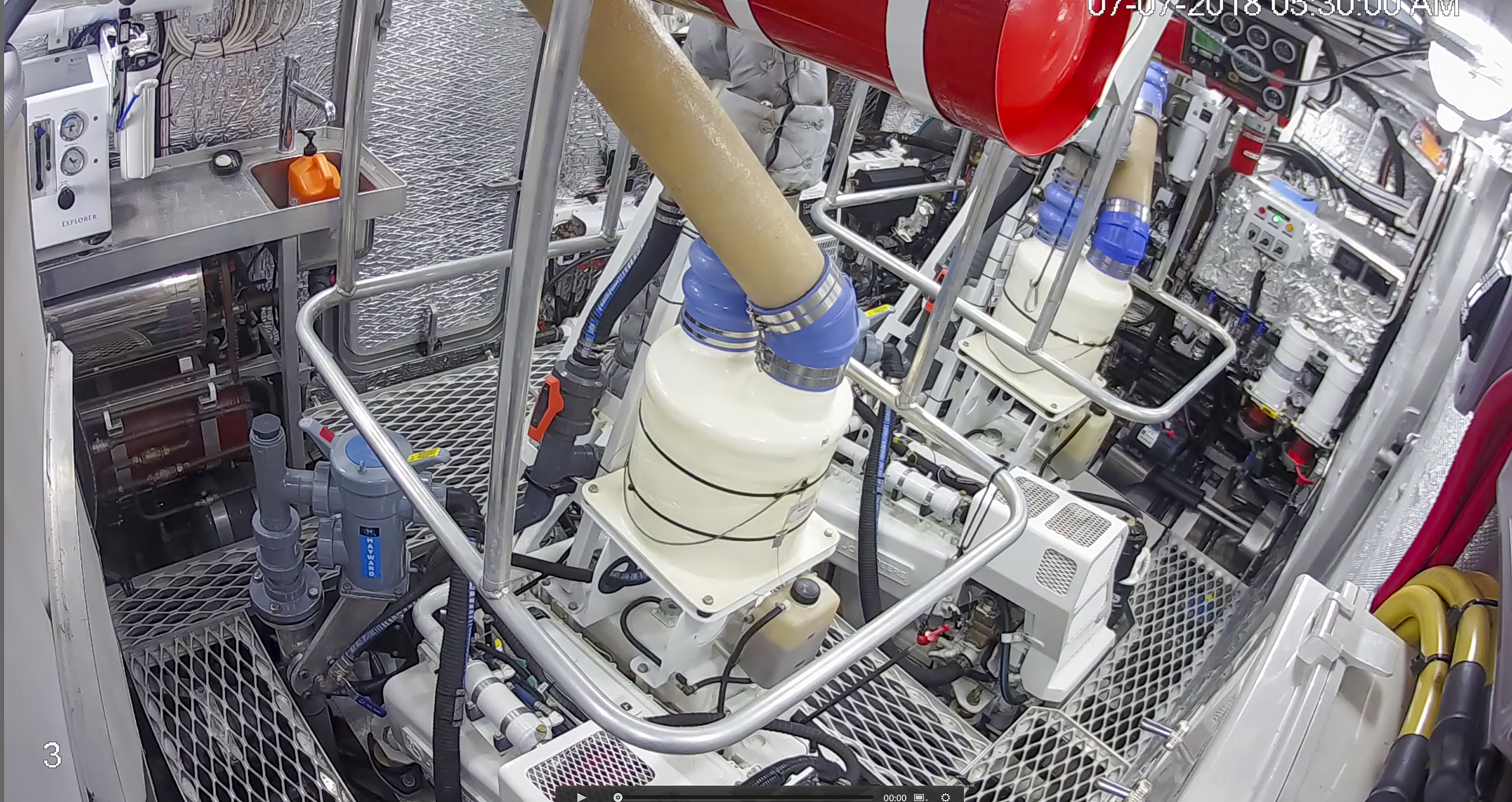

Last year we were talked into a high-res video camera system for keeping tabs on the engine room, seeing the blind spots otherwise invisible from the helm, and tracking sea state and machinery underway.

At first we thought this a mistake, but we have come to appreciate the information this makes available.

In particular those views of the engine room, of which this is one of three.

Drying Out

Since we’ve been chatting about docking a few words on the FPB 78’s ease of drying out are in order. The FPB 78’s are engineered to use a grid (shown above) or simply dry out on a tidal flat (below)

This has numerous maintenance benefits, opens up a totally new world of thin water cruising in areas with large tidal ranges, and offers a method of short term parking when space is at a premium and there is insufficient room to swing (as with several areas along the Intra Coastal Waterway).

Aft Deck Design Evolution, Function, and Dinghy Handling

One of our design goals with the FPB 78 was to be able to carry a sufficiently large dinghy that we could travel long distances with it in relative comfort, and that it could work as a life raft if needed. We also wanted to be able to run the dinghy at speed in the dark, if there was a requirement to do so.

Having spent a lifetime in sail, handling the booms and winches we use for launching and retrieving dinghies is second nature. It is also the most dangerous exercise there is aboard. So with these new FPBs we set out to simplify the rigging and make it easier to handle the dinghies, particularly in rolling anchorages. We spent hundreds of hours doing 3D simulations, more time during build with experiments and changes, and 17+ variations with FPB 78-1 in the water.

We settled on a 16-foot AB industrial version of their aluminum bottomed RIB. The dinghy is powered by a 60 HP Yamaha four stroke: quiet, efficient, and always starts on the first push of the button. We now carry 24 US gallons of fuel in a pair of plastic tanks. These are held in place by an aluminum framework that carries a camera box, and has space to hang grocery bags, visitors’ luggage, etc., inside a zip-up cover if it is raining. There is also a towing bit for towing heavy loads arranged so the dinghy can be steered when towing.

There is a tent covering the forward section to provide rain shelter and storage when needed.

The dinghy can now be launched by one person in under less than five minutes from start to powering away, faster if you are in a hurry. The two of us can bring the dinghy from shore to alongside Cochise, in the rain, and have it secured on deck so we are ready to put to sea, in under three minutes. Both actions can he done in a rolling anchorage if needed.

There is a video of launch and retrieval here.

Dinghies can be stored outboard of the lifelines, freeing the aft deck when we are at anchor.

The aft deck has been evolving since before we began cutting metal six+ years ago years ago.

The design today, after many iterations, is quite different from the original. For example, the area above the engine room air vent has gone from a simple seat and barbecue station to an outdoor galley and food prep area. There is a sink to the right, under a removable cover.

Circumnavigator Michael Morrell puts Cochise’s BBQ through its paces.

Circling back around to running the dink at night, and at speed, say for a medical emergency, we have experimented with a variety of forward lighting combinations.

By far the simplest and best approach were these four LED spotlights, sourced through Amazon. Two are aimed low, right in front of the bow, with the second set aimed about 150 forward.

Comforting Side Issues

As a part of the initial design parameters we set aside a significant budget for noise control in terms of weight, cost, man hours, and materials with the goal of substantially reducing sound and vibration levels under way. This involved changing structure, increasing mass and stiffness in the engine room, tripling the insulation in hull and deck, and installing sophisticated multi-layer sound dampening bulkheads. The result is the quietest boat we have ever been aboard at sea.

At anchor, we have experienced a pleasant surprise. The same combination of polar moments and stability curve that works so well at sea seems to be harder for the smaller waves of typical anchorages to excite, i.e. start rolling. And when movement does occur the period is so slow that it has rarely been necessary to use our big booms. After two years of experience we came to the conclusion that the booms were longer than needed and we reduced their length by ten feet/3m, reducing weight and windage, and making them easier to use.

Living the good life off the grid

The main driver in yacht systems design is how you approach air conditioning. In the tropics, most yachts require a generator 24/7 to provide power for the air conditioning. In the past, we used a combination of natural ventilation, awnings, and insulation, to reduce heat loads to where we could get away with running the generator just a few hours a day.

The large, highly efficient solar arrays with which these new FPBs are fitted have gotten us to a place where fine-tuning other parts of the equation can significantly reduce and/or eliminate generator time entirely.

Along with our usual approach to shading and awnings The FPB 78 has large overhangs on the Matrix and main deck. The grills above feed two 12″/310mm vents in the great room. The canvas hood over the top of the grills and down the sides improves airflow. These, in conjunction with the nearby windows, overhangs and deck create a ram effect that helps keep the air moving in the great room.

Two more vents are fed by these grills at the forward end of the great room.

We have enhanced the natural ventilation on the lower deck with the addition of passive vents in each stateroom fitted with pram hoods to help air flow. The heads and systems areas have large air removal fans installed.

Additionally, our normal heavy hull and deck insulation has been tripled. This helps with both temperature and noise.

The traction battery bank gives us 1560 amp hours @24VDC for the 20 hour rating (compared to 1200 amp hours on Wind Horse) and it is now possible to spend long periods at anchor with zero carbon footprint. Aside from helping the environment and having a quieter home, the elimination of the daily fuel burn from the genset significantly enhances the yacht’s endurance. Where most yachts Cochise’s size would require 20-30 gallons of diesel per day just for electricity needs at anchor, the FPB 78 uses little or none. This daily savings really adds up over a period of months, to the point where it can significantly impact how much fuel is left for passaging and/or how often you have to arrange to purchase fuel. In tropical Fiji with Cochise we averaged one hour of generator time every third day. When FPB 78-1 was docked in Fort Lauderdale, we didn’t even bother to connect the shore power cord. In the Bahamas in April, with warm water and air, we rarely needed the genset. The 16 solar panels produced between 18.5 and 32kWh of power every day.

Aft Space Bonus

One of the design advances that gives us the most pleasure is the change in the aft area of these new yachts, one that allows for both a spacious engine room and a separate, isolated area aft of this. On FPB 78-1 we are using the space as a combination workshop/crew accommodation. This area is referred to as the “Executive Lounge.” We think it is radically cool!

FPB 78 Performance

We have already discussed how much more comfortable the new FPBs are at sea than their predecessors, as well as their increased maneuverability. The question now before us is: what about fuel burn, speed and range?.

The FPB 78 has 60% more displacement than the FPB 83, and probably double the volume (counting the Matrix deck) of the FPB 83. Even so, at ten knots cruising speed, in calm conditions, the fuel burn is almost the same as the FPB 83. At higher speed length ratios, starting around 10.5 knots of boat speed, the fuel burn rate begins to increase compared with the much lighter FPB 83. Likewise, the additional windage costs us fuel burn upwind, but then pays a dividend by acting as sail area off the wind.

In terms of speed and range, the FPB 78 has a demonstrated capability to go 4,700 nm upwind in the trades against the prevailing waves and current, averaging ten knots speed over ground, with 500 gallons of fuel to spare. If you were going in the opposite direction, downwind with the current and waves, you could increase speed by over a knot, while reducing fuel burn, extending range to over 6,000 nm with the same surplus left over.

Maintenance