FPB 97-1 Iceberg running before a stiff breeze during sea trials.

The post that follows this introduction is a chapter excerpted from the FPB 70 and 78 Owner’s Manual. Everyone who goes to sea thinks and/or worries (or should) about heavy weather, and how their vessel will handle different conditions. It doesn’t matter whether you’re on a 25,000 ton container ship, a moderate-sized sailing yacht, or one of our FPBs. We think it is better to discuss these issues openly, rather than ignore them and hope you never get caught. We are sharing this chapter here because there are certain universal tenets when it comes to avoiding and/or handling heavy weather that apply to all types of craft.

We would caution readers that, in the material that follows, while there are many principles that apply in some form to most ocean going yachts, the tactics and details listed below are FPB specific. It should also be noted that sea states we might consider to be an exhilarating challenge, from the security standpoint of our FPBs with their stability curves, surfing ability, and steering control, would be thought of as survival storms in other types of vessels. At the end of the day, your definition of heavy weather will depend on the experience and psychological state of the crew and captain, along with the capability and condition of the yacht.

We invite you to share your own heavy weather experiences via the comment section at the end of the post.

FPB 70/78 Owners’s Manual: Heavy Weather Preparation, Avoidance and Tactics

Understand Weather

The single most important thing you can do towards successful cruising is to get a feel for onboard weather forecasting. This helps you stay out of unpleasant situations in the first place, get a handle on the storm structure from onboard observation, and then adopt the correct tactics. It also pays dividends for picking anchorages and knowing when to get out. At the end of this post you will find URLs where you can download free copies of our Mariner’s Weather Handbook and Surviving The Storm.

Access to weather models and professional weather routers are a help, but this is no substitute for what you can deduce by tracking barometric pressure, wind direction, wind speed, and cloud types. And in really difficult conditions your onboard forecasting capability is absolutely critical to making the best use of the tools which the FPB puts at your disposal.

If you think that a shore-based weather router will save the day, think again. Modern weather forecasting tools can be quite accurate in terms of energy flows over wide swaths of the Earth. But when you focus down to the area where you are located, there can be major variations between what you observe and what the weather models and/or router has predicted.

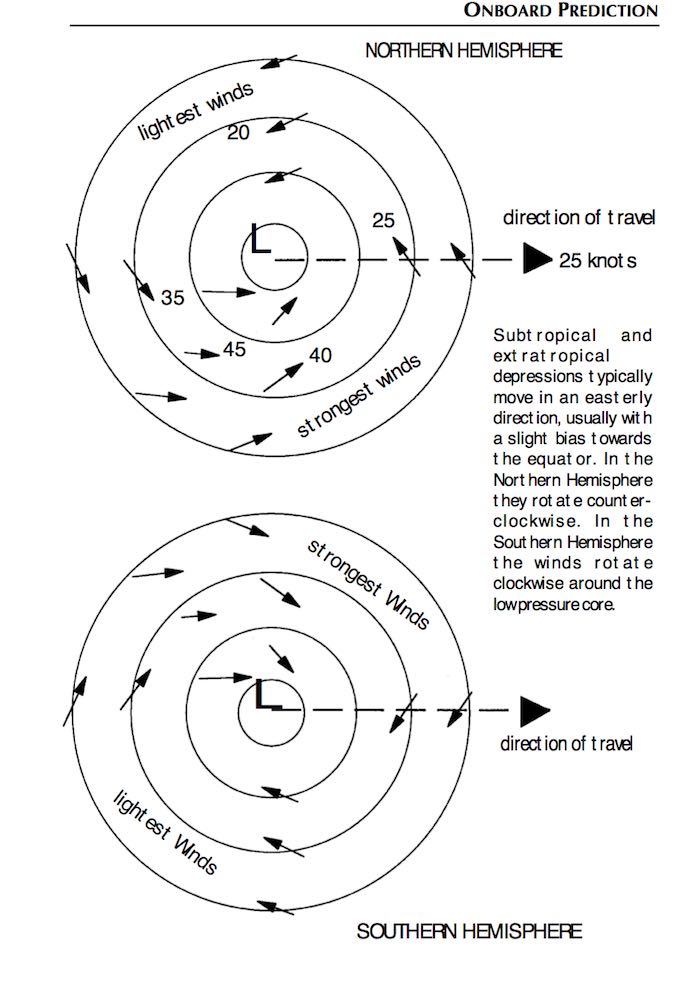

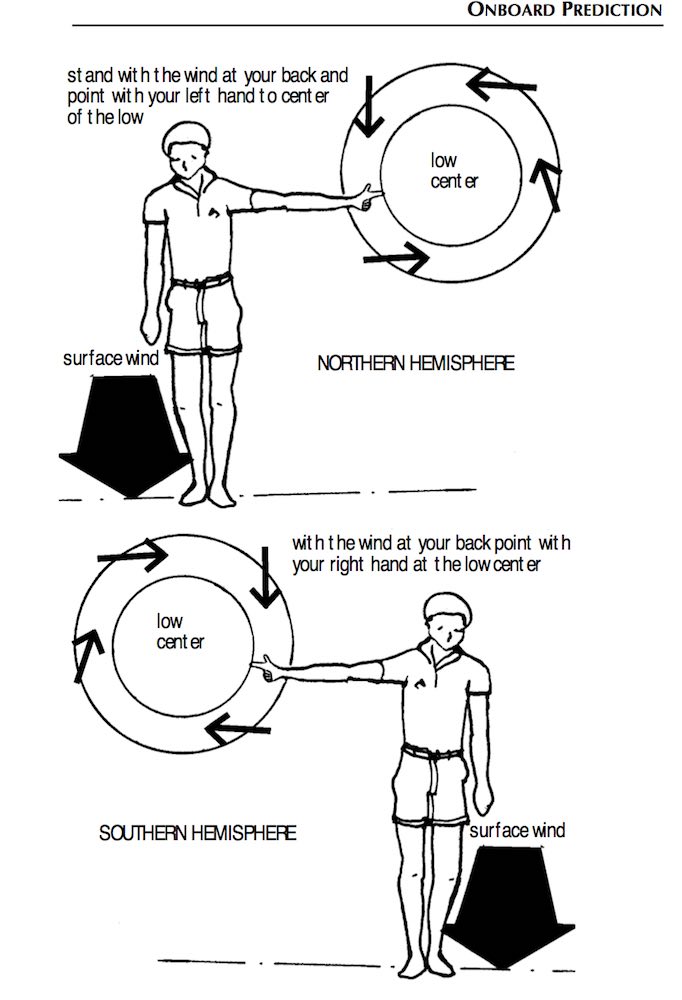

(The sketches above are excerpted from Mariner’s Weather Handbook.)

This is not to say that professional routers are not a valuable resource. Quite the contrary. But we feel safest if we are in a position to frame the context in which they create their forecasts, and then discuss the variables and risk factors. In this regard, we have found it necessary to impress on forecasters the high average speed we are capable of maintaining, along with what we consider acceptable sea states. This will be quite different from their usual yacht clients – power or sail.

Here are a few items to be sure you understand:

- 500 mb weather – the key to almost everything that happens on the surface.

- How to determine storm centers by changes in wind direction and barometric pressure.

- The difference between conventional (Norwegian) storm structure and baroclinic (bent back) storms.

- Compression storms.

- The storm sector with the most survivable conditions.

- Tropical storm structure.

- How to anticipate tropical storms transitioning to extra-tropical.

- Impact of subsurface bathymetry (underwater topography) and opposing current on waves.

- Dynamic wave fetch.

- Land influence of wind and sea states.

We guarantee you that expending the effort to understand these factors will be the best investment of time towards safe and comfortable cruising you ever make.

Weather tends to be pattern-based. There is often a rhythm to the progression of highs and lows. These patterns will vary from year to year. We have found it helpful to begin watching the weather closely three to four weeks ahead of our desired departure date, to familiarize ourselves with how the season is working out. It often helps to chat with local met experts to get their take on the patterns they see and how these may vary from the norm. On occasion an upper level feature will establish itself where it spits out a continuing stream of atypical unpleasant weather. In this case it may be best to be patient.

An example of this is the passage from New Zealand to Fiji, where departing with the leading edge of a high usually guarantees a quick and easy trip. Your 4.5 days (or less) underway typically keeps you within the benign influence of the high. Even more important is getting north of the storm track, which takes 2.5 to 3 days.

Another example is heading east to French Polynesia, leaving on a leading edge of a high pressure system. As long as you can average 10.5-11 knots, in most cases you will see no more than one weather system sandwiched between two highs.

Here is what John Henrichs, one of our most experienced and sea savvy owners, has to say:

“Watch the trends and once you are satisfied, contact your professional and see what they think about your departure date. If the professionals say don’t go, then you need to figure out what you missed and learn from it. I find the more I learn, the more often I am challenging the router to explain more, and the last couple passages, I found things the router didn’t pick up. Not that I am better, but after 5 seasons crossing the same areas I keep learning more about the area. I would add to never stop asking questions from cruisers that have far more experience in areas than I do.”

Steve Parsons, a professional sailor with extensive FPB 64 and FPB 78 experience adds:

“Given the speed and efficiency of the FPB, there would usually be no reason to get ‘caught out’ on a passage of 3 days or less, it’s really the longer passages where you have to deal with what you get outside of the long range forecast.

Studying weather patterns long before your expected departure is time well spent. Also try to have a plan for alternative ports, although this isn’t always possible. Follow a range of online forecasting sites; by studying 4 or 5 it is easier to spot any anomalies by comparison, especially outside the 72 hr forecasts, at which point they can be much less reliable. In NZ/Pacific waters, we tend to use Metservice, Metvuw, Passage Weather, Predict Wind, and Grib Files. It is a valuable learning exercise to study an isobaric analysis, draw your own 24/48 hr forecast, then compare it to the prognoses. This is a useful way to familiarize yourself with local weather trends. Weather routers can be a useful ancillary tool, but remember, as has been stated elsewhere, no one knows the local conditions better than the person who is actually in those conditions and knows how to read the sky and seas.

Finally, a word on high pressure systems and your boat speed. Once you can average ten knots or more it becomes possible to ride high pressure systems towards your destination, or cross them while they block unpleasant weather. The high may be moving at 12 to 15 knots or it may be stationary, but the faster you go the longer you benefit from it.”

Vessel Preparation

Most major sea going problems start out small. Really serious issues, in particular those associated with extreme weather, are usually the result of a cascade of events, the beginning of which was preventable.

Take care of anything that can impact your speed, steering, and watertight integrity before you leave. We always inspect steering gear, including fastener torque on cylinders, tillers, drag links, etc. The drive line and high load engine accessories are checked. A detailed check list applicable to your own vessel is recommended.

Insure that interior storage areas are appropriately stowed and deck gear is all lashed in place, under the assumption that unpleasant weather is on the horizon. If you have large areas of storage, such as in the FPB 78 forepeak or FPB 70 basement, pay particular attention to storage security. Heavy gear that comes adrift can do significant systems damage.

Inspect the boom control hardware and the securing of the booms themselves. Where there are boom control struts, as on the FPB 78, check bolt torque on boom connection collars, track bolts, and articulating ball joints at strut ends.

There should be nothing lashed to the foredeck unless it has been properly engineered, i.e. the secondary anchor. Dorade vents should be secured from the interior, and cowls removed with solid covers inserted.

Rig jack lines on the exterior, and extra manlines around the aft deck and interior. Dinghies may benefit from a secondary set of lashings.

Finally, the single biggest impact on boat speed and maneuverability is the condition of props, fins and hull. Take the time to have these cleaned before every passage.

Practice

We recommend testing various wave angles, steering settings, speeds, and crew whenever the opportunity arises to give the boat a good workout. Lying a-hull with and without stabilizers, heaving-to with and without them, and jogging are all worth practicing.

Experiment with different boat speeds while jogging into the seas. Imagine a breaking sea suddenly coming from your beam (i.e after a frontal passage). You will probably find a combination of rudder and throttle is required to make the fastest 90-degree turn.

Put in some time steering with the emergency JOG lever (which gives you direct control of the rudders without autopilot finesse). Experiment with this upwind, cross wind and downwind.

The rudder speed doubling “docking pump”, which brings a second hydraulic pumpset online, will often be beneficial in weather scenarios requiring aggressive steering.

If you carry parachutes or drogues, the crew should be familiar with their deployment and retrieval.

Payload

Each FPB type has an optimum loading for heavy weather. Carrying payload greater than this amount can be a negative. It slows you down, makes the boat less responsive to helm, reduces usable downwind speed conditions, and makes the boat more susceptible to wave impact.

The FPB’s massive fuel and water capacity make it easy to overload. Generally speaking, if you are heavy with fuel, go very light on water. Replace the mass of fuel as it is burned with water. If the water maker fails, you can always introduce salt water into an empty fuel or water tank as an emergency replacement. In worst case situations, salt water can be mixed with the understanding it is going to take a while to clean up the resulting mixture.

Press Tanks

A partially filled tank creates substantial free surface loads, which reduces your stability. This is most acute in near-knockdown situations. Manage fuel and water so that tanks that are being used remain filled other than the one from which you are drawing.

Longitudinal Trim

Generally speaking, each FPB has an optimum trim angle for maximum efficiency in normal sea states. However, when you are contemplating bigger sea states, steering control and minimizing propeller air entrainment become the dominant criteria. Both of these favor stern-down bow-up longitudinal trim.

Autopilot Settings

The Simrad pilot is easily programmed for different steering modes. At present you can have six of these. On Cochise we have one setting called Heavy Running and another called Maneuvering. Heavy running is self explanatory. Maneuvering is normally used just for docking, but would probably also work well in severe upwind slow jogging conditions.

NAIAD Settings

Whether the fully automatic ‘adaptive’ or modifiable ‘at speed’ settings work best will be determined by trial and error over time. In a heavy weather context watch out for excessive stabilizer angle, which leads to stabilizer fin stall, and the accompanying momentary loss of speed from the greatly increased drag.

If the Stabilizers Fail

We have been lucky so far with few underway stabilizer issues. But if they do fail there are several things to consider. First, be sure the fins are locked on center. Be aware that with fins centered, abrupt directional changes will cause the centered stabilizers to generate lift forces that will heel the boat, so limit steering input to a minimum.

Choose a course that avoids beam or nearly beam seas, and avoid angles that expose you to harmonic rolling (where your natural roll period is a harmonic of the wave period).

Experiment with different speeds. Generally speaking, faster is normally more comfortable than slower.

Check the Route

Have a close look at the various route options for deep underwater obstacles and navigate around these if there is any risk of surface interaction. An underwater ridge that goes from a depth of 5,000 ft to 1,000 ft can set up a chaotic sea state, sometimes in relatively benign conditions.

Use Your Seat Belts

Your FPB is equipped with seat belts on the bunks and in several seating areas. Use them! They will keep you much more comfortable and prevent bodies from flying around after major wave impacts.

Psychology and Remaining Alert

It is not unusual for a crew that is tired and deeply concerned with the situation to be unable to make decisions. The boat is left to its own devices, and the risk profile increases. Confidence in your equipment, which comes from preparation and practice, helps keep your mind at ease, and rest is a powerful antidote. Husband your energy early on. You may need it later in the blow. Finally, we have found that food is a great morale booster. An inventory of easily warmed pre-cooked meals and snacks can do wonders.

Tactics

There is no magic bullet, no single tactic that can be used in all situations. As wind and sea conditions change your strategy may need to adapt as well. The worse the situation, the more involved you will need to be. You cannot close your eyes and wish the conditions away.

Be particularly alert if the wind suddenly dies as the sea state, now without wind pressure, can become chaotic. Wait until the sea state has stabilized–it will eventually drop over time–before relaxing your vigil.

Keep in mind that the FPB gives you the ability to maintain high average speeds through a variety of adverse wind and wave scenarios. Thus, you have a much wider range of options than you may have been used to with other yachts. In particular, you may have the ability to change position within the storm to reduce risk from wind, wave, or navigation obstacles.

In the most extreme conditions, the tactics that you employ will ultimately depend on your stability and the capability of the yacht to deal with breaking seas. All yachts have their greatest stability when taking seas end-on, either bow or stern into the wave, and the least stability when beam-to.

The photos which follow were taken in 35 knots of wind as FPB 64-1 Avatar was leaving Whangarei, New Zealand. The river tide is ebbing against prevailing wind and seas, hence relatively steep waves. Avatar is fully loaded for her first trip to the tropics and she is running at just under 11 knots, showing off for photographer Ivor Wilkins.

![]()

In this first shot Avatar is doing what she is supposed to do, penetrating the wave.

![]()

Now a series, climbing a larger sea.

![]()

![]()

She is now partially airborne.

![]()

![]()

And now almost fully airborne.

![]()

In this spectacular (albeit unusual) return to the trough it looks like there’s a lot of water coming on deck, but in terms of stability or structure, it’s a non-issue. Note that the layout of the foredeck, and elimination of deck edge bulworks, makes it nearly impossible to accumulate significant quantities of water.

Sometimes moving the boat at speed from one position to another will feel like your FPB is being really punished. If you are wondering what sort of a pounding these hulls can take, your feet will give you a sense of what is going on. When you are in the Great Room, and your feet stay on the sole when you drop into the trough the forces are less than one “G”. You are not yet beginning to tax the boat.

The boat can take a lot more than the human body. In the process of moving your FPB, you may think you’re beating the s**t out of her, but she is perfectly happy.

The above photos and discussion are in the context of moving the boat to avoid the worst parts of a severe weather scenario. Here is a list of some items to think about:

- Forecast storm track, signs it is or is not adhering to the plan, with notes on what to expect.

- Alternate plans in case development of weather is different than anticipated.

- Tidal currents, ocean currents, and their impact on sea state.

- Water temperature variation and its effect on wind and lightning.

- Navigation obstacles.

- Undersea features which may create localized wave chaos.

- Intermediate harbors of refuge that can be safely entered in adverse weather.

- Position within the storm.

Wind and sea states typically vary, sometimes substantially, around the center of a storm system. The more speed and steering control you have at your disposal, the greater your options of improving the conditions with which you must deal.

Most tropical systems (typical hurricanes) have their strongest winds within a 30-to-50 mile radius of the center. Where you might have 80-knot winds 20 miles from the center, at 50 miles you might be down to 35 knots. Extra-tropical storm systems are much larger. But even here a couple hundred miles can make the difference between an interesting experience and survival conditions.

Speed and Maneuverability Are the Keys

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, boat speed and steering control are the key ingredients in determining which tactics make the most sense. When running off, the faster you go the fewer waves overtake you, and the more time you have to react to them. Your rudders and stabilizer fins generate force in proportion to the square of the boat speed, so small increases in boat speed go a long way in helping with control. If you are running at 9.5 knots and up the RPMs to where you are surfing at 13.5 knots, your fins will generate twice the force.

Watching Waves – Visibility at Night

Our experience is that you can often see large crests some distance off, even on moonless nights. With a bit of moonlight and dark adjusted eyesight, you will usually have a pretty clear indication of what is coming.

In really difficult sea states, given sufficient crew, the ideal is to have one person on the controls and a second calling dangerous waves. And of course there are the LED flood and spotlights forward that will help as well. In fact, an extra set aimed aft could pay big dividends in heavy downwind running.

Steering Around Dangerous Seas

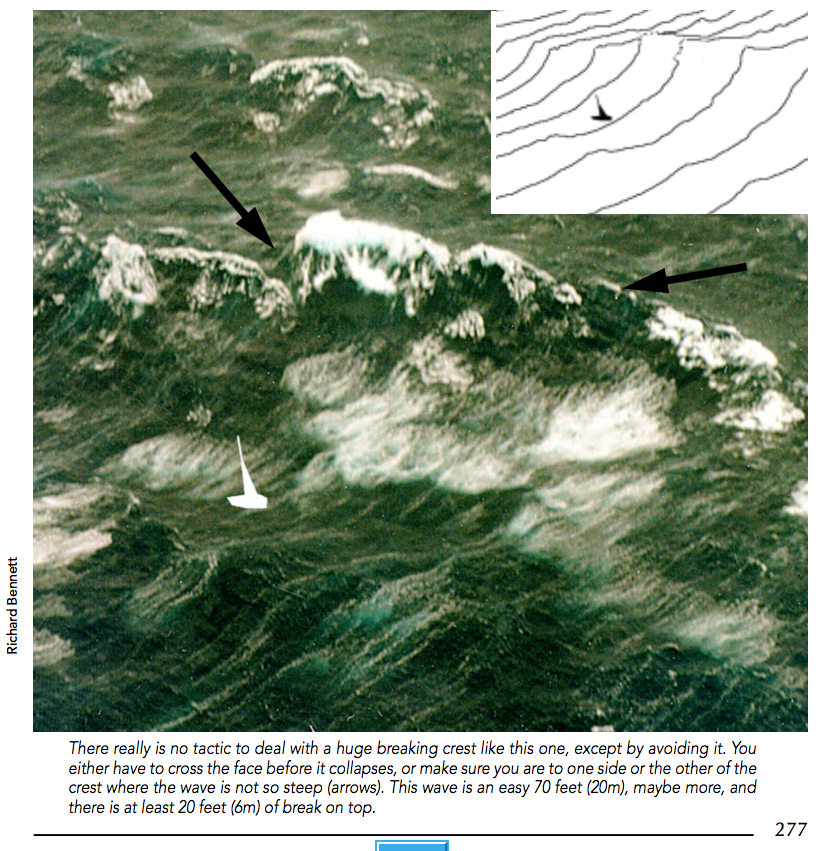

Dangerous seas sometimes have escape routes, areas along the wave face that are not breaking or have smaller crests. There are times when the transition region is abrupt, sometimes even vertical. With sufficient boat speed and maneuverability plus situational awareness, you can take advantage of these escape routes, as shown below in the excerpt from Surviving the Storm.

Skid Factors

All of the FPBs are designed to skid sideways under wave impact as they begin to heel (as in all of our sailboats). Skidding allows the yacht to absorb the energy of breaking seas over time, like slipping with a punch in the boxing ring. The ability to skid enhances survivability regardless of a yacht’s stability curve. Here are a few skid design factor considerations:

- Rounded bottoms, in particular avoidance of bottom to topside chines, reduces heeled resistance.

- The smaller the heeled “draft” the better yacht will skid.

- Narrower hull beams skid better than beamy hulls.

- How keel, rudders, stabilizers, etc. project into the water with heel is a major factor. Ideally, as you heel most of these projections are lifted clear or close to parallel, with the direction of skid so as to offer minimum resistance.

Running With the Wind Aft

Given clean running gear, fins and hull, and moderate loading, it will be unusual to encounter conditions where you cannot continue to run directly downwind at speed, having great fun surfing.

10 to 15’ (3 to 4.5m) waves like these from the stern quarter don’t begin to register on the adrenaline scale (FPB 83-1 Wind Horse en route from New Zealand to Fiji).

Assuming downwind is where you want to go, this is often the best way to get yourself off the storm track. This is another example where your understanding of the weather system you are dealing with is essential.

The FPB 78 and 70 have extra freeboard forward, and the positive angle of attack this gives the belting (rub rail) and anchor platform creates dynamic lift if the bow is buried into a wave.

There are two scenarios we have found where it pays to start thinking about heading upwind. The first is if there is a danger of driving the bow deeply into the back of the wave ahead of you as you surf at too high a speed. If this results in a rapid deceleration, and the wave behind you breaks as you are slowing, a pitchpole or severe broach is possible.

The cresting sea in the middle background, if it caught the bow or stern, would require significant rudder input to maintain heading. It is about twice the size of the average waves. Check out the sea further out at the horizon. The first two days of this passage to Fiji aboard Wind Horse we’d see these every hour or two, but never came into actual contact.

When running at high speeds with crossing seas and/or steep waves, adjusting course up from a dead run may reduce the chances of “stuffing” the bow. When the decks start getting wet with solid water, that is a signal that something needs to change.

No longer being able to control direction of travel is another sign that it’s time to think about different tactics.

Speed, surfing, wave shape, and steering are all linked.

Sometimes adding RPMs will result in faster speed and better control. Other conditions may warrant a bit less RPM, with occasional RPM increases to help with steering. Sea state and wind speed tend to change constantly, and it is not uncommon to need to play with RPMs and course.

During sea trials with FPB 78-1, we found ourselves in a rapidly increasing 35-50 knot breeze as we headed north to the Bay of Islands. Cochise was lightly loaded at the time, carrying approximately 2500 gallons of liquids. Towards the end, with the steepest seas, we were running at 2000 RPM with surfing speeds consistently at 13.5-22 knots. There were several times when we overran the wave we were riding and buried the bow right to the belting in the back of the wave ahead of us; in none of these cases did we ever pick up any solid water on deck. On three occasions we started to round up off course 10-20 degrees, with heel to 15-30 degrees, a situation in which you would expect a broach. However, each time the autopilot steered us back on course with our speed in the high teens or above, never dropping. In thinking about this after the fact, we realized that the key to Cochise’s ability to steer her way out of these incipient broaches was her boat speed. Anything significantly slower and we would have been testing our skid factors. However, if we had been in the open ocean and there was a crossing swell, we would have had to reduce our surfing speeds to maintain control.

There is a short video below that is intended to be watched with this section. It will give you an idea of what the FPB 70 and FPB 78 are capable of when surfing at high speed. Cochise is close enough to shore that there is a periodic cross chop from reflected waves. We are pushing very hard, looking to define the limit of her maneuverability when surfing at high speeds.

The video focuses on rudder angle, course over ground, boat speed, and heel angle. Watch how the autopilot brings Cochise back onto course with minimal rudder input, very little change in speed, at heel angles as high as a momentary 30 degrees. The way in which this all works is an indicator of how hard you can push. We think we are close to the limit for this type of situation.

At the end of this post is a link to the longer video from which this extracted.

Wave shape, speed, and direction relative to your course along with crossing swells (if present) will be the final arbiters in the decision to turn around and jog into the seas.

We should point out that in all our years at sea, we have never encountered conditions that would preclude us from running at speed with either the FPB 83 or 78.

Making the Turn

The turn into the seas means exposing your beam to a possible breaking crest, so picking the right time to make the turn is important, as is turning quickly. However, using too much rudder and trying to turn too rapidly will cause the rudders to stall, props to cavitate, resulting in a slower turn, and may induce extra heel. This is one of those areas where previous practice will now pay dividends, since you will know the ideal combination of rudder angle and RPM to use.

Fore Reaching

In the very worst conditions it may be safer to fore reach, keeping waves at a 30-to-60 degree angle off the bow and heading up directly into the breaking crests. This is done at a higher speed than jogging directly into the waves, and affords the opportunity of accelerating across a wave to an escape area.

Jogging Directly Into Seas

This is the traditional motor vessel tactic of heading slowly into the seas. It is adopted early by most vessels, due to lack of steering control and the risk factors associated with conventional stability curves. We mention this not to disparage other designs, but so that you are not confused by the fact that everyone else does it differently. Simply put, with the FPB we have a variety of heavy weather tactics we can use that are not part of the normal motor yacht arsenal.

Wind Horse in 55 knots true wind speed, with seas 10-20 degrees of the bow. It looks exciting but there is very little motion.

If your destination is downwind, or if you need to move downwind at an angle to the true wind direction to escape a storm center, then jogging into the seas becomes a final option only when running off is no longer possible. Choosing an optimum speed is a function of wave shape. Faster is better in that you will have more control with rudders and stabilizers. But you don’t want to be going so fast that you break through the crest and then find yourself unsupported and dropping deeply into the oncoming wave trough.

When conditions are sufficiently boisterous, it is worth working throttles and occasionally the helm to mitigate motion. Steve Parsons comments:

“On Cochise in Bligh Waters, Fiji, we found ourselves punching into a sea with an unusual period and steepness, and, partly for the comfort of guests, we juggled the throttles continuously to best handle each wave–speeding up over the smaller ones, and throttling back for the steeper, cresting waves, which was every 6th or 7th. The boat’s motion was also exacerbated by the fact that we had inadvertently made too much water and were slightly trimmed by the bow–the only time we have shipped green water over the bow.”

Heaving To

During sea trials aboard FPB 78-2, Steve Parsons discovered that Grey Wolf II would lie quietly with the bow at about 30 degrees off the wind, with the leeward engine ticking over slowly. Steve found that they would round up and fall off, as if hove-to under sail (but at a closer angle to the wind). By adjusting RPM, FPB 78-2 would hold station in four-to-five meter seas and gale force breeze.

Steve Parsons adds some important details:

“There are times when ‘heaving to’ into the seas is the wisest decision. By doing this you may be under the influence of the storm system for less time than if you were running off (and possibly away from your destination).

By putting the seas on the shoulder (at about 30-60 degrees) and applying revs to the leeward engine, you can adjust the autopilot settings so the vessel rounds up and drops off continuously, much like a sailing vessel hove-to. Of course fetch, period and steepness of waves, etc. will all determine the best throttle/helm combinations to use, so experiment when you find a seaway and it’s not in the heat of the moment. You will need to keep on enough speed to maintain rudder authority, and jogging into a steep sea.”

Beam Seas

You would normally not expose your beam to dangerous seas, as this is the direction from which there is the least stability. However, if tactical or navigation requirements dictate this be attempted, generally speaking the faster you go the better. Stay at the helm ready to head up into breaking crests.

Crossing Wave Patterns

In all the decisions we have been discussing, the dominant factor in making them is sea state and how your FPB is reacting to the conditions. With a single set of waves you can push harder, faster, and through much rougher conditions than will be the case with one or more crossing swell states. Heavy weather with a single wave system is certainly not the norm in our experience. Rather, there always seems to be another system or two of waves, often generated by weather thousands of miles away. When you are heading uphill, occasionally the dominant and crossing swells combine to create a peak or deep valley, which then makes itself known with a perceptible bang. Heading downhill they sometimes will give the bow or stern a good slap. These impacts are typically transitory, last a few seconds, and often follow no set pattern. But if the upset of the natural rhythm is substantial enough, it will end up determining the speed at which you want to run. This is true on normal passages as well as in heavier going.

This eight foot (2.4m) crest is skewed about 60 degrees from the dominant wave system. Its impact will be mainly noticed from noise it creates.

When you are dealing with frontal weather, as the warm sector gives way to the cold the wind will swing through 90 degrees. If conditions are severe, the new waves from the cold sector will at first be quite steep, and the general sea state can quickly grow chaotic. Which direction you head depends on where the most dangerous waves appear to be coming from. This of course can change in the blink of an eye. That’s when the big rudders and maneuverability come into play.

This next series of photos were taken off the south end of Cowes in the UK in gale force breeze, tide against wind situation. This is not recommended, and if you are in these conditions you will want the Dorade vents stored and sealed (unlike what is shown here). In spite of the way this looks, the amount of water on the foredeck will clear quickly.

Recap

Having a strong, heavy weather capable, and sea kindly yacht like the FPB is not a license to ignore weather risk factors, or to take chances that you might not take in a lesser vessel.

Paying attention to weather, and making the right decision to depart, should be based on weather risk factors and not on ideal schedule.

Of all the items we’ve been discussing, nothing is as important to safe ocean voyaging as the yacht’s preparation and skill level of the crew.

We have learned over the years that rather than accepting forecast data – whether model output or the result of professional forecasters – it is best to look for the warning signs that point to risks not indicated in the current forecasts. If you are dealing with a weather router, ask if there are alternate negative scenarios on which they might be keeping an eye, and the probability of these occurring; you will on occasion get some surprising answers.

We want to reiterate that overloading your FPB by carrying large volumes of fuel and water, in many situations will lead to lower factors of safety, and the loss of some attributes which make it possible to take in stride conditions others might find threatening. Please keep in mind that the huge fresh water capacity is there in the event that you want to replace the weight of fuel as it is burned. We do not recommend carrying both full fuel and full water.

Finally, your ability to maintain high average passage speeds is the most important tool you have in making safe, comfortable, and fun passages. Speed is one of the key ingredients to avoiding dangerous weather in the first place, and a critical component of the range of tactics available to you if you do get caught. Correct vessel loading, clean propellers, fins and hull, and preventative maintenance, are all integral to safe, comfortable, and enjoyable cruising.

Links:

Download Surviving the Storm and Mariner’s Weather Handbook

Video of Trawler Capsize: Amazing footage of a trawler capsizing in extreme conditions, with slow motion analysis.

Video of FPB 78-1 Running at High Speed (longer video referenced to in post): Running off before a rapidly rising gale, with winds up to 50+ knots, in extremely steep seas.

Video of FPB 78-1 off the Bay of Islands in New Zealand: Beating in moderate conditions, 20-25 knots, with just a hint of FPB 78-1’s potential in high winds.

Video of FPB 97-1 Iceberg in Heavy Weather: Running off before a 50-55 knot gale.

Other heavy weather and stability posts:

Motor Yacht Stability and Capsize

July 20th, 2017 at 1:26 pm

Hello Steve. You mention practicing “jogging”. I don’t know that expression – what is it? Best regards.

July 20th, 2017 at 9:29 pm

Hi Markus:

Jogging, as we understand it, means heading slowly into the seas, until conditions allow you to continue on your way at normal cruise.

July 20th, 2017 at 1:29 pm

Like every sensible sailor, we don’t go looking for bad weather and do our best to structure our passages to take advantage of good weather windows. After all, this is supposed to be fun. Our two worst weather experiences aboard Iron Lady occurred of the east coasts of the North and South Island of New Zealand during our circumnavigation of same in 2012. The first occurred off the Banks Peninsula on the South Island. The second when we were rounding East Cape on the North Island. Both blows occurred in the dead of night (they always seem to).

Off the Banks Peninsula, nothing was forecast but we started to see lightning around 1900. The wind came up and by midnight, it was blowing 60 to 70 knots. That lasted until about 0500 when things calmed down and we were able to run in to Akaroa and drop the hook. We were later told in town that they get 1 or 2 of these micro storms a year and they are rarely forecast. Considerable damage had been done shoreside. For us at sea, visibility was zero as the foam, spray and darkness made it impossible to see anything. As such, I cannot tell you how high the waves were as we punched into them, but the motion was violent enough that the boat was being launched off the tops and was crashing into the troughs on the far side. The boat seemed to handle it all without difficulty and both the autopilot and stabilizers were up to the task. Our first strategy was to throttle back to reduce our speed but as the seas built, we bore off about 30 degrees and everything calmed down dramatically. At that point, it simply became a matter of waiting it out but there was no sleeping aboard that night even in the aft quarters.

In the case of East Cape, we knew we were going to get about 12 hours of difficult weather. It really came down to a matter of choice. We were departing Picton via the Cooke Straight and a major gale was forecast for the following days if we delayed our departure. For those who have been there, the Cooke Straight is no place to be in a strong gale so we made the decision to leave when the weather was benign. That meant that we would,, however, encounter a lesser blow off East Cape with wind and seas right on the bow. In most respects, it was a replay of our Banks adventure – 10 to 12 hours of 50 plus knot winds. Again, as it was night and the sea state was such that I cannot honestly say how big the waves were. We applied the same strategy as off Banks. Throttle back and bore off while maintaining our general course until things subsided.

Those kinds of conditions have been the exceptions. Even on our long passages – NZ to French Polynesia – French Polynesia to Hawaii – Hawaii to British Columbia the seas were generally less then 5 meters and typically were more like 3 to 4. I can only recall two or three nights that I couldn’t sleep in the forward master state room even though a good portion of some of those passages were uphill.

July 21st, 2017 at 10:17 am

While quartering into seas after leaving New Zealand, Wind speed 20 to 25 knots, seas 4 to 6 feet, we were hit by a breaking wave Square on our starboard beam. The wave initially rolled us to Port and the breaker slid us down the wave face on our beam

completely dissipating the wave’s energy. Just as advertised by the designer.

July 26th, 2017 at 12:23 pm

From FPB 64 Toccata owner Chris Groobey:

“I noted the guidance in the piece that one needs to be careful about overloading the boat with too much fuel and water. The piece suggests, for example, that one should start a long passage very light on water if starting with full fuel tanks, and then use the watermaker to fill the water tanks over time to match the amount of fuel that has been consumed.

Being a 64 owner, I wonder how much this advice applies only to the 70/78 series, since this piece was written for their owners’ manual. I don’t have a reference to the 64 manual handy but I believe the 70/78 advice differs from the guidance in the 64 manual (and generally the owner scuttlebutt) that 64s are happiest when all the tanks, both fuel and water, are full.

What’s the best way to learn whether the guidance is only for the 70/78 designs or also applies to the 64s?

July 31st, 2017 at 5:14 pm

Hi Chris:

From the design perspective, the massive tankage of the FPBs in general allows you to maintain stability and trim when low on fuel. That is where the large fresh water tanks come into play. The best answer is going to be very much a question of personal preference as to motion and the sea state. Personally, we prefer a boat that is light on its feet as opposed to sluggish. With both FPB 83-1 Wind Horse and FPB 78-1 Cochise, if we are heavy with fuel we minimize fresh water. If we think we want a large supply on hand once anchored we will wait until the last 24 hours at sea before making our own fresh water.

Carrying both fresh water and fuel tanks full, in your case more than 5000 US gallons if memory serves me, is going to give the boat a more ponderous feel, and cost you some boat speed or fuel burn.